ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Knowledge gaps and research priorities for understanding the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other airborne infections

J. Peter Cegielski1, Sevim Ahmedov2, Jun Cheng3, Collin Dubick4, Emily Evans5, Paul A. Jensen6, Avinash Kanchar7, Anita Rani Kansal8, Che-Chi Lin9, Yuhong Liu10, Michael Marll11, Gyanshankar Mishra12, Matsie Mphahlele13, Edward Nardell14, Jako-Albert Nice15, Jerod N. Scholten16, Carrie Tudor17, Martie van der Walt18, Helene-Mari van der Westhuizen19, Varvara Vauhkonen20, Richard L. Vincent21 and Grigory Volchenkov22

1Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; 2Bureau for Global Health, TB Division, USAID, Washington, DC, USA; 3Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China; 4Department of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; 5Division of Infectious Diseases, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; 6End TB Transmission Initiative, Stop TB Partnership, Geneva, Switzerland; 7TB Prevention, Treatment, Care & Innovation Unit, Global Programme on Tuberculosis & Lung Health, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 8National Institute of TB and Respiratory Diseases, New Delhi, India; 9Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA; 10Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China; 11Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA; 12Department of Respiratory Medicine, Indira Gandhi Government Medical College, Nagpur, India; 13The Aurum Institute, Parktown, South Africa; 14Division of Global Health Equity, Brigham and Woman’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; 15Department Architecture and Industrial Design, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, GAU, RSA; 16Division of TB Elimination and Innovation, KNCV Tuberculosis Foundation, The Hague, The Netherlands; 17Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, MD, USA; 18Independent Consultant, Pretoria, South Africa; 19Nuffield Department of Medicine, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom; 20Independent Consultant, Helsinki, Finland; 21Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; 22Independent Consultant, Vladimir, Russia

Abstract

Despite 5 years of SARS-CoV-2 research, as well as decades of research on tuberculosis (TB), large gaps remain in understanding the transmission of airborne pathogens. Our aim was to delineate these gaps. Understanding them would enable evidence-based, practical efforts to reduce transmission. Building upon the 2017 Roadmap for TB Transmission Science, we interviewed experts in the field and identified six salient topics harboring holes in knowledge that impede prevention and control efforts. These include 1) fundamental elements of aerobiology, 2) detecting and measuring infectious respiratory particles directly in the air, 3) the infectiousness of asymptomatic TB (by extension, other lung infections) and 4) of calm tidal breathing – including their contributions to global epidemiology, 5) the role of ‘superspreading’ in disease incidence, and 6) the duration of infectiousness of highly drug-resistant TB treated with the newest, all-oral short-course regimens. Based on an extensive literature review, we update advances in science since 2017 and then summarize knowledge gaps and research priorities. Several recent systematic reviews all noted the relatively low quality of published research, so there is an overriding need for high-quality studies to provide evidence for national and international entities upon which to base recommendations, guidelines, and standards.

Keywords: tuberculosis; SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; airborne infections; airborne transmission; infectious aerosols; infection prevention and control

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2025, 21: 23851 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v21.23851

Copyright: © 2025 J. Peter Cegielski et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 7 May 2025; Revised: 17 July 2025; Accepted: 30 July 2025; Published: 13 October 2025

Competing interests and funding: All authors declared no conflicts of interest. This report was funded by the Stop TB Partnership with funds from the U.S. Agency for International Development (Grant number: STBP/USAID/GSA/2024-04 in support of ‘End TB Transmission Initiative – Powering Airborne IPC (ETTi)’).

*J. Peter Cegielski, MD, MPH, Department of Epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health Emory University, 1518 Clifton Road, CNR 3038 Atlanta, Georgia 30322 USA. Email: peter.cegielski@emory.edu

To access the supplementary file, please visit the article landing page

An estimated one-fourth of humankind is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, 10.4 million people develop tuberculosis (TB) disease annually, and 1.3 million die (1). TB is preventable and curable, and in adults, it is relatively easy to diagnose, yet it kills more people than any other single infectious disease. Humanity is not on target to reach the ‘End TB’ goals endorsed by the World Health Assembly and the United Nations (2).

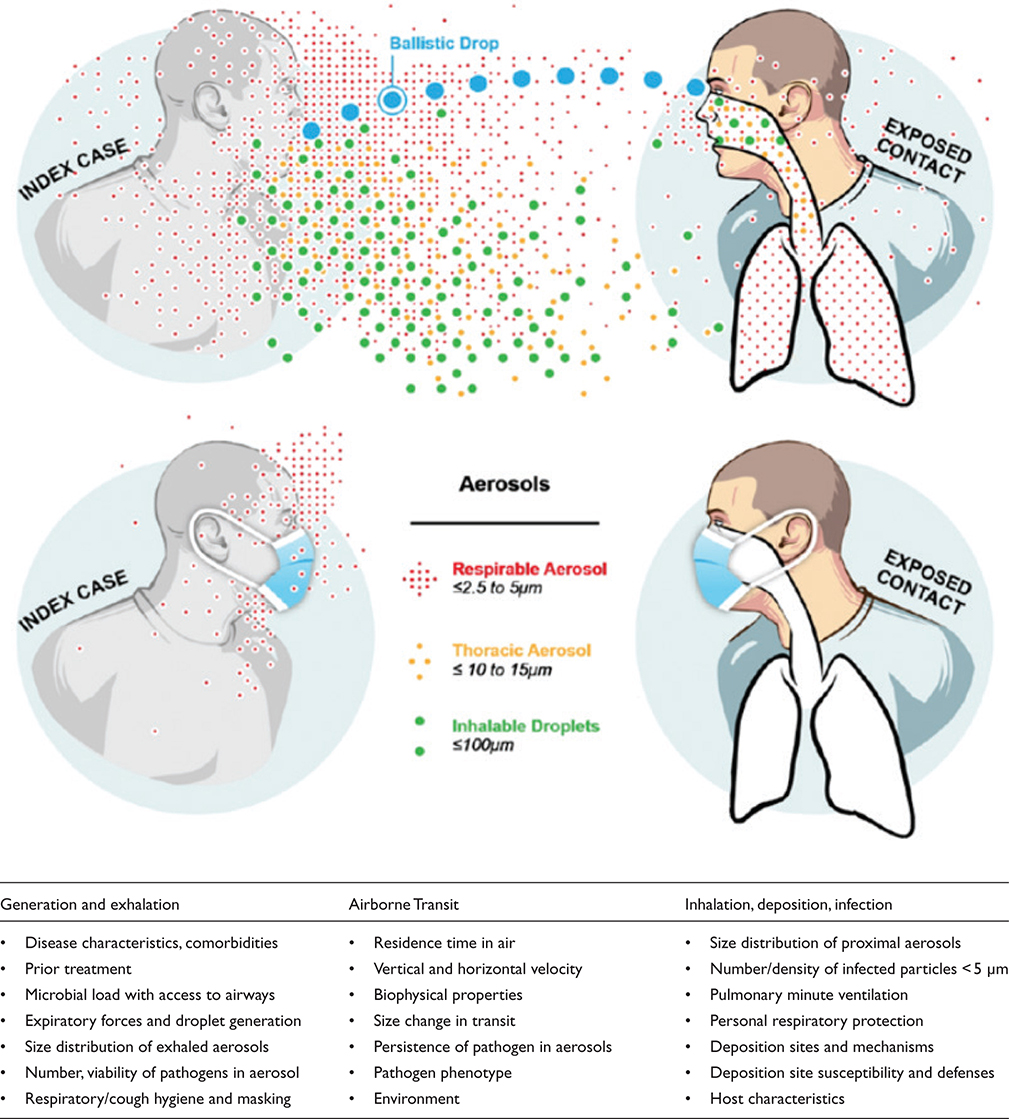

Ending the centuries-long TB pandemic means stopping transmission of M. tuberculosis, a prototype of true airborne infections. In broad terms, the transmission of airborne pathogens like M. tuberculosis is determined by five main factors: 1) unique pathogen characteristics, 2) infectious source case traits, 3) initiation and efficacy of treatment, 4) risk factors of exposed potential hosts, and 5) the environment in which source, pathogen, and potential hosts come together (3, 4). Human proximity to an infectious source is also required for transmission. The greatest risk occurs in indoor environments, especially where air dilution is limited and ventilation is poor. Before treatment, the burden of pathogens within the lungs and airways is associated with the risk of transmission. Cough frequency, forcefulness, and, for TB, the extent of cavitary disease also increase transmission (Fig. 1) (5–7). Despite these principles, TB transmission events and outbreaks are heterogeneous, so much remains to be learned (8–10).

Fig. 1. Airborne transmission of respiratory pathogens. Three components: 1) generation and exhalation of infectious particles, 2) airborne transit of particles to a susceptible person, and 3) inhalation, deposition of particles, infection in the new person. (Adapted from Milton DK, 2020, Doi: 10.1093/jpids/piaa079).

A seminal series of reports in 2017 delineated then-current knowledge in TB transmission science and mapped research needs, where knowledge was sparse (11–16). The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic stimulated research on the transmission of pathogens via infectious respiratory particles (IRPs), including aerosols that are inhaled and tiny droplets that land directly on a recipient’s mucosa (collectively, ‘airborne’) (17). Compared with TB, SARS-CoV-2 transmission has distinct characteristics due to its differing transmission dynamics and epidemiology. Our aim here is to update advances since Auld et al.’s 2017 article titled “Research Roadmap for Tuberculosis Transmission Science” (13) adds data on COVID-19 and highlights persistent gaps in current knowledge. We then suggest research needs to fill those gaps. Recent high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses covered various aspects of airborne infection prevention and control (IPC), including triage, respiratory isolation, treatment, respiratory precautions, environmental measures, and personal respiratory protection (5, 18–22), but not transmission science itself – the interdisciplinary study of how pathogens move through the air from one host to another, integrating the underlying biology, physics, environmental science, behavioral factors, and epidemiology that affect this process.

Following the selection process described later, topics that rose to the top in the scientific literature and dominant issues articulated by experts coalesced into two broad themes: 1) transmission and infectiousness, and 2) prevention and control. This article focuses on infectiousness and transmission research published subsequent to 2017 (13). In this context, infectiousness means expelling functional bacilli into the ambient air. Transmission means those airborne bacilli are inhaled by another person, replicate, and initiate an infected focus. A separate, companion article focuses on infection prevention and control.

Methods

We conducted an extensive review of peer-reviewed literatures published between January 2017 and April 2024, using PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. Search terms included combinations of ‘tuberculosis’, ‘drug-resistant tuberculosis’, ‘multidrug resistant tuberculosis’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘transmission’, ‘airborne transmission’, ‘aerosol transmission’, ‘infectiousness’, ‘respiratory aerosols’, ‘respiratory droplets’, ‘subclinical tuberculosis’, ‘asymptomatic tuberculosis’, and ‘early bactericidal activity’. We included original research articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published in English that reported original data using credible methods, scouring their references for additional articles. We also reviewed the latest authoritative guidelines and recommendations issued by leading professional organizations and public health agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), ASHRAE, and others.

We interviewed 12 members of the Stop TB Partnership’s working group (Supplementary material) and End TB Transmission Initiative – Powering Airborne IPC (ETTi) (https://www.stoptb.org/who-we-are/stop-tb-working-groups/end-tb-transmission-initiative; all of whom are actively engaged professionally in airborne transmission science and program applications. Interviews were conducted using a standardized method centered on eliciting limitations of current knowledge and research needs. We organized the interview results into ~80 themes, excluding topics covered in six recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses as noted above (5, 13–17). We then asked the entire ETTi membership to rank the results in priority order. Together with the literature review, the highest-ranking themes formed six sections of this report integrating advances identified in the professional literature with current knowledge gaps and pressing research needs.

Results

Our review and interviews identified recent advances on six salient topics:

- Aerobiology

- Detecting and measuring infectiousness directly

- Infectiousness of asymptomatic TB

- Infectiousness of tidal breathing

- Super-spreaders

- Duration of infectiousness of M/XDR TB treated with new drugs and regimens

Aerobiology

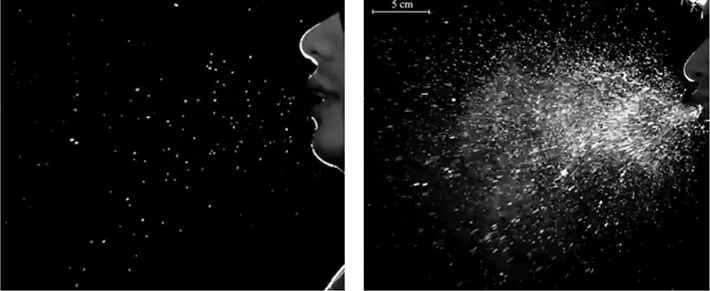

In the past decade, research has advanced our understanding of respiratory droplet and aerosol behavior in various environmental conditions.5 Advanced particle imaging techniques, including high-speed cameras and laser light scattering, demonstrated that respiratory particles can remain suspended for hours under certain conditions (Fig. 2) (6, 23). The size distribution and environmental fate of respiratory emissions have been characterized in unprecedented detail, revealing complex interactions between particle size, environmental conditions (temperature and relative humidity), and transmission risk.7 Particles follow complex trajectories influenced by thermal plumes, room air currents, and human movement patterns. These air movement patterns influence microbial decay rates as well as the spatial distribution of particles. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling has enabled researchers to visualize and estimate aerosol dispersion patterns in detail (24, 25), revealing that traditional assumptions about droplet settling times were oversimplified. Particles can remain airborne significantly longer than previously thought due to dehydration, air currents, and environmental factors. Studies utilizing state-of-the-art bioaerosol sampling techniques and molecular detection methods reaffirmed that IRPs containing M. tuberculosis primarily exist in the 1–5 μm diameter range that can remain airborne for extended periods and penetrate deep into bronchiolar and alveolar space (23, 26). The composition of these particles – salts, pH, proteins, mucins, and other biological materials – significantly affects survival rates (27, 28). The knowledge gaps and urgent research needs are to determine the extent to which advances related to SARS-CoV-2 aerobiology apply to M. tuberculosis and other pathogens. In addition, aerobiology results must be correlated with actual transmission events because countless more respiratory particles are produced than infections – most particles contain no microorganisms, infectious particles settle, microbes are compromised in transit, and some are inactivated after reaching a target. Each of these steps and mechanisms spotlights knowledge gaps and corresponding research opportunities.

Fig. 2. High-speed videography captures airborne particle production. Digital transformation quantifies number, size, distribution, trajectory, and refractile characteristics. Single frames selected from 5 s videos. Left: droplets generated by speaking the word ‘three’; right: droplets generated by sneezing. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNeYfUTA11s.

Detecting and measuring M. tuberculosis in the air

Infectiousness and transmission of TB are associated with positive sputum microscopy and culture, cavitary lung disease, as well as cough intensity and frequency (3), reflecting tools developed over a century ago (29). They do not measure the density of particles containing viable pathogens suspended in ambient air (30). How we can best measure infectiousness directly in research, clinical, and public health contexts remains a major blank in knowledge needed to prevent and control transmission.

New tools that measure viable, emitted pathogens are transforming our understanding of transmission. Direct air sampling and face-mask sampling combined with newer detection methods suggest calm tidal breathing aerosolizes bacilli, and asymptomatic individuals transmit infection. These advances uncovered gaps in understanding airborne transmission that apply across pathogens and the corresponding priorities for further research and development of sampling and detection methods. In 2013, a Cough Aerosol Sampling System (CASS) predicted transmission to household contacts better than conventional sputum microscopy (31). The more recent Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber (RASC) measures both particles and microbes in ambient air in an otherwise clean chamber, differentiating those produced by talking, coughing, tidal breathing, and other respiratory maneuvers (Fig. 3) (23, 29, 32).

Fig. 3. Respiratory Aerosol Sampling Chamber. In the middle, a photograph of the RASC, door open. On the sides, each of the systems and instruments attached to the chamber. 1) Aerodynamic particle sizer, 2) filter samplers, 3) Anderson impactor, 4) mixing fan, 5) CO2, temperature, humidity, 6) PM10 impactor, 7) subject’s chair inside (Adapted from Wood 2016, Doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146658).

CASS and RASC systems are research tools, but they could lead to the development of less expensive and less technically demanding technologies for clinical and public health applications. The next steps are to adapt, improve, and develop such sensor systems into more widespread, economical, and practical real-time utility. They must be validated against human-to-human transmission data including all age groups to determine how accurately they measure real-life transmission risk.

Air sampling by portable, high-flow dry-filter units using specialized filters is a promising technology (33). Face-mask sampling of exhaled breath captures pathogens immediately as they exit the mouth and nose on specialized material embedded in the mask (Fig. 4) (34–36). These techniques use detection methods such as droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR), microfluidic chips, or PCR that targets alternative genetic loci, showing higher sensitivity and specificity than conventional methods (33, 37–39). In one study, ddPCR detected M. tuberculosis in 25 of 35 (71.3%) 1-hr aerosol samples from newly diagnosed pulmonary TB patients, whereas culture on solid media detected 15 (42.8%) (40). These investigators estimated a median of 0.9 CFU/10 liters (interquartile range [IQR]: 0.7–3.0) of expired air (among the culture positives) and a median of 4.5 × 107 CFU/ml (IQR: 2.9–5.6) of expired particulate bioaerosol. M. tuberculosis was detected the most at respiratory particle sizes 2.5–3.0 μm, although particles change over time as moisture evaporates. Nucleic acid amplification-based methods, however, do not distinguish fully functional from non-viable or functionally impaired microorganisms. Vital staining and microscopy have been explored to address this problem, albeit with limited sensitivity and practicality, but targeting messenger RNA (mRNA) has been proposed because mRNA has a half-life of minutes. Detecting intact mRNA indicates transcription took place within a few previous minutes in real time (41). New research on distinguishing fully functional, potentially pathogenic bacilli from all other bacilli is an urgent need and prime research opportunity.

Fig. 4. Face-mask sampling devices (top) and portable, high-flow, dry-filter air sampling devices.

The ability to detect and quantify bioaerosols in real-time has been advanced significantly with the development of portable biosensors and environmental monitoring systems (42) (https://www.innovaprep.com/products/acd-200-bobcat-air-sampler; https://www.cbrnintl.com/SASS_3100_air_sampler.html; accessed 3/3/25). Recent innovations include the use of bioaerosol sampling devices equipped with next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, allowing rapid identification of airborne pathogens in healthcare and community settings (42, 43). Advances in biosensor technology have made it possible to continuously monitor the concentration of airborne pathogens in indoor environments (44). These technologies are not yet ready for targeted or widespread implementation. These advances in technology create opportunities for ambitious, transformative research and engineering ranging from molecular biology and aerobiology to clinical and public health applications.

These new tools should be applied to the full spectrum of TB and other airborne infections. Studies must include the impact of specific characteristics and comorbidities – such as early childhood, HIV co-infection, diabetes mellitus, and other pulmonary diseases – on aerosolization, infection, and diagnostic outcomes, including high-HIV-prevalent regions (45–47). Research should explore transmission dynamics in diverse real-world settings, such as healthcare facilities, congregate and community settings, schools, work places, public transportation, and other gathering places (48, 49). While foundational principles may remain consistent, pathogens differ, and current research in highly controlled environments may not fully capture the complexity of transmission in everyday contexts that span naturally ventilated, mechanically ventilated, and unventilated spaces (50).

Infectiousness of asymptomatic TB

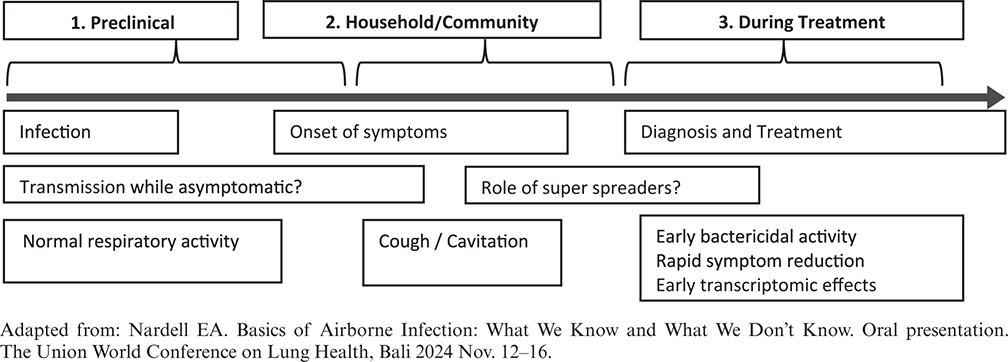

Recent studies focused attention on unidentified transmission from asymptomatic TB and its potential contribution to global disease burden (Fig. 5). This work spotlighted major gaps in knowledge, technology, and policy development as well as research needed to fill those gaps (51–53).

Fig. 5. When is most TB transmission occurring?

Definitions of asymptomatic TB vary, though efforts have been made to characterize disease states correlating with signs, symptoms, and infectivity, providing a framework for future research, diagnosis, and management (53). WHO recently proposed explicit definitions for asymptomatic TB across the spectrum from initial infection to fulminant disease (www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2024/featured-topics/asymptomatic-tb#refs). Definitions used in case identification play a crucial role in determining asymptomatic disease and in interpretation of retrospective data. In addition, self-report of symptoms during active screening activities has limited validity due to broad variation, as well as confounding by stigma and polluted air that causes coughing. Thus, further research on screening or testing is needed. This is another major research need: better characterizing infectiousness and transmission associated with infection/disease states previously missing from global public health discourse.

Based on 28 prevalence surveys in Asia and Africa, evidence suggests a median 50.4% (IQR 39.8%, 62.3%, range 36.1–79.7%) of adult TB cases are asymptomatic (54). An individual patient data meta-analysis of 12 surveys in similar geographies reported that an unadjusted proportion of 39.8% (36.6, 43.0) of identified TB cases had no cough, while 20.3% (15.5, 25.1) had no symptoms at all. Corresponding adjusted proportions were 82.8% (78.6, 86.6) and 27.7% (21.0, 36.4) (55). These investigators emphasized overreliance on screening for persistent cough. Cough may be the only recorded symptom used for case identification even though it is present in less than 50% of clinical cases (55, 56). Accurate determination of true prevalence remains a priority for further research to reinforce or refute the theory that asymptomatic disease represents an unrecognized medical and public health need and opportunity for prevention.

WHO 2024 Proposed Definitions of Asymptomatic Tuberculosis (57)

- TB disease: a person with disease caused by the M. tuberculosis complex

- Asymptomatic TB: A person with TB disease who did not report symptoms suggestive of TB during screening

- Asymptomatic TB, bacteriologically confirmed: A person with bacteriologically confirmed TB who did not report symptoms suggestive of TB during screening

- Asymptomatic TB, bacteriologically unconfirmed: A person with bacteriologically unconfirmed TB did not report symptoms suggestive of TB during screening

During contact investigation, the diagnosis of asymptomatic TB is typically established radiographically, at least initially. In Peru, approximately 2% of asymptomatic close contacts were diagnosed with TB compared with approximately 20% of symptomatic close contacts (54). Contacts who had abnormal baseline chest radiographs thought not to be TB had a 15-fold increased risk of downstream diagnosis compared to contacts with normal radiographs, suggesting missed diagnoses (58). Radiography may reveal severe disease associated with transmission of infection to others despite a paucity or absence of symptoms (59). Direct evidence of asymptomatic TB transmission can be found in a study of Vietnamese children, in whom comparable rates of infection were associated with contact with asymptomatic versus clinical TB case contacts who themselves had positive sputum microscopy, with relative risks of 3.1 and 3.6, respectively (60). Small pediatric studies from low TB burden European countries also suggest a high proportion of asymptomatic TB, ranging from 30 to 60% of cases, with increased detection using advanced imaging modalities (61, 62).

Mathematical modeling studies estimated an almost two-fold relative infectiousness risk per unit time for asymptomatic TB compared with clinically overt TB, translating to upwards of 68% of transmission. The assumptions on which such estimates are based, however, lead to considerable uncertainty (63). Well-designed prospective studies with rigorous methodology to identify patients with asymptomatic TB, COVID-19, and other airborne infections are needed to better clarify the true prevalence, transmission risk, and the possibility for interruption at the population level (64).

Infectiousness of tidal breathing

Dinkele et al. found that tidal breathing accounted for the release of aerosolized M. tuberculosis in up to 90% of symptomatic patients (65). Tidal breathing for 5 min generated an average of 104 (8) particles; ~2/3 of them had 0.5–1.0 micron diameters, small enough to remain suspended and inhaled deep into the lungs. Roughly 1/10,000 contained viable M. tuberculosis, although particle count and recovery of M. tuberculosis did not correlate. For each 5-min sampling period, 63–64% of samples were positive having 2–3 bacilli on average (20 maximum). Spontaneous coughing during the period of calm tidal breathing doubled both particle counts and bacillary counts. Forced coughing produced 10-fold to 100-fold more particles, but not more bacilli. Tidal breathing produced 93% of the total number of bacilli excreted, while coughing produced between 3 and 7%. Collectively, these findings challenge dogma that cough drives infectiousness. One must keep in mind, however, that a forceful, incessant cough differs greatly from a slight dry cough. These data need further investigation, including the role of open cavitation, HIV infection, and early childhood. A tiny fraction of airborne microscopic particles with culturable bacilli (or detectable virions) cause infections. One cannot draw conclusions about transmission from these data. They quantify the crucial first step en route to the next host. If true, these findings would up-end current IPC practices and policies for small droplet- and aerosol-transmission. Confirming, modifying, or refuting these findings with different methods in different contexts are high priority for future research.

Apart from CASS and RASC systems, Williams et al. detected M. tuberculosis in 86% of face-mask samples of 24 symptomatic patients during normal respiration using face-mask sampling for 8 h in a 24 h period, significantly higher than 21% detected through sputum analysis (47). Two more studies demonstrated that viable M. tuberculosis can be aerosolized during normal breathing, even without coughing (40, 66). Viable, however, is not synonymous with infectious or even culturable. The crucial gap in knowledge is, which of these methods best indicates (risk of) transmission. The production of M. tuberculosis-containing bioaerosols varied greatly between individuals (32, 40, 67). Individuals with advanced pulmonary TB, severe lung disease, or frequent coughing were more likely to aerosolize mycobacteria and spread infection. These findings collectively spotlight the need for a broader understanding of respiratory behaviors in TB other airborne transmission, emphasizing that normal breathing plays a crucial role.

With respect to SARS-CoV-2, Stadnytskyi et al. reviewed the biophysics of droplet and aerosol generation in relation to breathing, coughing, sneezing, speaking, and singing (68–71). In enclosed spaces, calm tidal breathing resulted in progressive accumulation of suspended infectious particles even though expiratory airflow was less turbulent with smaller sheer forces and generated lower liquid volume.

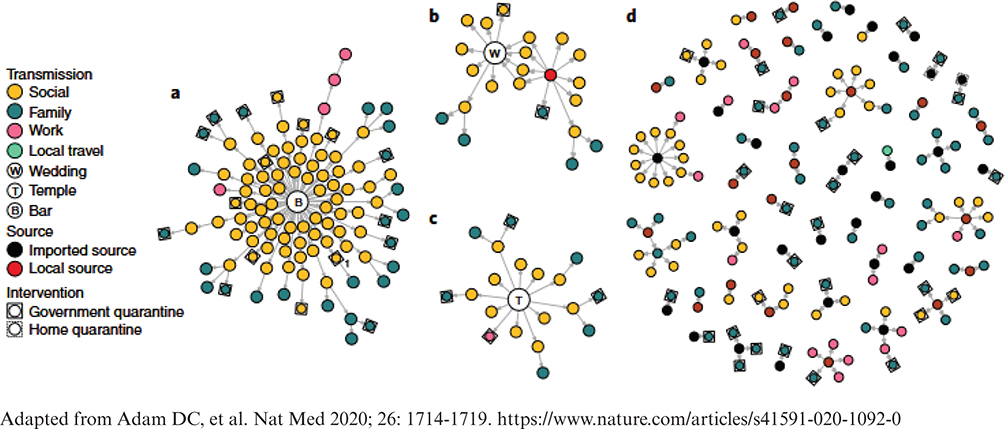

Super-spreaders

The concept of super-spreading, where a small proportion of infected individuals transmit pathogens to a disproportionate number of others, became popular due to innumerable SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks (Fig. 6) (72). This terminology was applied to TB more recently although the principle was documented in the 1950s (73). Molecular genetic methods enable transmission chains to be traced with unprecedented accuracy (31), although slowly mutating pathogens, such as M. tuberculosis, can be difficult to trace because of low genetic diversity, especially when a dominant strain(s) prevails in the population. Research on super-spreading is urgently needed; existing knowledge is sparse with little empirical observational or experimental data to date (74) such that this phenomenon is not well-understood (31, 75). Super-spreading through discrete events (or exceptional source cases) may be the opposite end of a spectrum from transmission from calm, tidal breathing or from asymptomatic TB. Each of them has been proposed, with good reason, to account for a majority of transmission; however, both cannot be true at the same time. Much remains to be learned.

Fig. 6. SARS-CoV-2 transmission networks in Hong Kong. (a) ‘Bar and band’ cluster with no known source (n = 106); (b) Wedding cluster without clear transmission pairs linked to a preceding gathering (n = 22); (c) Temple cluster of undetermined source (n = 19); (d) All other clusters where source and transmission could be determined.

In Botswana, Smith et al. quantified TB’s effective reproductive number and characterized the high degree of individual heterogeneity in transmission to others (76). In rural and urban areas, 99% of secondary transmission was traced back to 19 and 60%, respectively, of infectious cases. Both populations experienced large outbreaks due to recent transmission, especially in rural areas. Such individual-level heterogeneity in transmission shapes local epidemiology. Extending their work to a systematic analysis, Smith et al. quantified global transmission dynamics based on surveillance studies having whole genome sequencing (77). Although the reproductive number was consistently <1.0 (range 0.10–0.73), the estimated dispersion parameter ranged from 0.02 to 0.48, suggesting large individual-level differences in transmission. At the population level, 2 to 31% of index cases gave rise to 80% of TB transmission. Identifying and accounting for the causes of this heterogeneity presents a research opportunity with substantial potential impact on prevention and control measures.

In Australia, a study with 4,190 active cases and 18,030 contacts from 2005 to 2015, ‘the dispersion parameter…for secondary infections’, estimated at 0.16 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.14–0.17), and there were 414 (9.9%) super-spreading events. Of the 3,213 secondary infections, 2,415 (75.2%) were due to these super-spreading events (3). Transmission leading to active TB disease had an even higher level of heterogeneity (k = 0.036 [95% CI: 0.025–0.046]). Thus, super-spreading events produced a majority of secondary infections.

Super-spreaders tend to have delayed diagnosis, high bacterial or viral loads, cavitary disease (in TB patients) on chest radiographs, frequent and forceful coughing, and increased social interactions, especially close or prolonged proximity with many individuals (59, 69). Enclosed, poorly ventilated environments contribute to super-spreading events. Other than these obvious risk factors, the root causes of super-spreading and transmission heterogeneity remain obscure and must be better understood to curtail transmission. These are important gaps in knowledge where research is needed to prevent and control transmission of airborne pathogens.

Compared with TB, COVID-19 super-spreading events have distinct characteristics, primarily due to the different transmission dynamics and epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. At the same time, contributing environmental factors may be similar – enclosure, congregation, crowding, and ventilation. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis determined that 3% of COVID-19 index cases infected >5 secondary cases. Super-spreaders were significantly more often symptomatic, middle-aged (49–64 years), or had >100 contacts (78). A comprehensive meta-analysis revealed that approximately 20% of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals were responsible for 80% of secondary transmissions (69, 79). The super-spreading pattern in COVID-19 has been associated with social congregation, environmental factors, and viral shedding patterns; super-spreading events were more likely in poorly ventilated indoor spaces (k = 0.1 [95% CI: 0.05–0.2]) (80). How much of this heterogeneity is pathophysiological or microbiological and how much is simply due to the number of contacts remains unclear. Understanding the mechanistic differences between TB and COVID-19 super-spreading has important implications for disease control strategies as they may require different interventions facilitated by early identification of super-spreaders.

Duration of infectiousness M/XDR TB treated with new drugs & regimens

Studies estimated the loss of transmissibility for drug-susceptible TB to vary from 48 h up to 6–7 weeks after treatment initiation, depending in part on how infectiousness was measured (4, 81, 82). Microbiological tests such as conversion to negative of serial sputum microscopy and culture are not consistently reliable markers of ongoing infectiousness while on anti-TB treatment (83). Moreover, M. tuberculosis can persist in sputum for months after treatment initiation in a viable but non-culturable state, further complicating the utility of these tests for infectiousness. Nevertheless, many countries and clinicians continue to implement a 14-day isolation period after treatment initiation before deeming an individual ‘non-infectious’ (83).

In contrast, the infectious period of M/XDR TB patients after the initiation of new, shorter, all-oral treatment regimens has not yet been well documented. Better data are needed.

Optimal treatment of M/XDR-TB depends on drug susceptibility testing, which takes time. Patients may be started on ineffective regimens initially, prolonging their infectiousness. In general, compared with drug-susceptible TB, MDR-TB is equally or more infectious (9). With the newest, all-oral 6-month regimens for M/XDR-TB, how long patients should be separated from other people is unknown. As with drug-susceptible TB, conversion to negative of serial sputum microscopy or cultures is inconsistent as a marker of infectiousness (83). Studies show a higher degree of variability in transmission rates of MDR-TB (84–88). Now that the overall duration of treatment is the same, one may ask whether the duration of transmission risk and isolation period should be the same.

The only direct measurements of the duration of MDR-TB’s infectivity come from a specialized Airborne Infections Research Facility in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, where air from patient rooms is ducted through guinea pig cages in a highly controlled manner (Fig. 7) (89). Dharmadhikari et al. analyzed data from five separate human-to-guinea pig studies of MDR-TB transmission for participants starting treatment (90). Participants received levofloxacin, kanamycin, ethionamide, and ethambutol or prothionamide, which is less effective than newer treatment regimens. Transmission abated within 24 to 72 h (90). In these studies, the transmission of MDR-TB was attenuated at rates comparable to drug-susceptible TB upon initiation of effective anti-TB treatment (91). Despite the limitations, this study supported implementation of community-based ambulatory treatment of MDR-TB (92).

Fig. 7. Airborne Infection Research Facility, Witbank, South Africa. Left: Exterior view; Center: Floor plan of research ward and animal rooms; Right: Guinea pig chambers with air ducts for controlled air supply. Photos courtesy of Grigory Volchenkov.

More recently, two novel regimens were studied at this facility. Patients in the first cohort were treated with an optimized regimen, including bedaquiline and linezolid. In the second cohort, they were treated with the BPaL regimen, bedaquiline, linezolid (1,200 mg), and pretomanid (93). The investigators measured baseline infectiousness by exhausting ward air to one of two guinea pig exposure rooms, each containing 90 GPs. After 72 h of treatment, ward air was exhausted to the second guinea pig exposure room. Guinea pigs were exposed for 8 patient-days for each group. In the first cohort, before starting treatment, five DR-TB patients infected 24/90 (26.7%) animals, while after 72 h treatment, the same patients infected 25/90 (27.8%). In the second cohort, nine DR-TB patients infected 40/90 (44.4%) animals before treatment. After 72 h of BPaL, the same patients infected 0/90 (0%) guinea pigs (P < 0.0001). Therefore, transmission was rapidly and completely inhibited in patients treated with BPaL for 72 h, suggesting the combination with pretomanid had a profound impact in contrast with the ‘optimized’ regimen that also included bedaquiline and linezolid (94).

Although this is the first and, to date, the only study to measure infectiousness directly after starting treatment with newer, all-oral regimens, two conventional study designs provide data on the speed with which culturable bacilli decrease then disappears from serial sputum specimens. Early bactericidal activity studies measure the daily decrease in culturable bacilli in sputum over the first 2 days to 2 weeks of an experimental treatment (95). In time-to-conversion studies, sputum samples are cultured weekly or monthly to determine how long until those cultures become consistently negative (77). This study design estimates the duration of infectiousness based on culture and quantifies the decrease from pre-treatment levels.

Two new drugs, bedaquiline and pretomanid, and two repurposed drugs, linezolid and fluoroquinolones, are cornerstones of the modern M/XDR-TB treatment (96). In early bactericidal activity (EBA) studies, the mean (± standard error of the mean [SEM] daily drop in CFU/ml with bedaquiline by itself (−0.06 ± 0.07) was least, while pretomanid (200 mg) by itself was nearly twice as high −0.11 ± 0.07, similar to combinations of bedaquiline-pyrazinamide (−0.13 ± 0.10) and bedaquiline-pretomanid (−0.11 ± 0.05). The 3-drug combination of pretomanid-moxifloxacin-pyrazinamide (−0.23 ± 0.13) was twice again as effective and faster than standard 4-drug treatment for drug-susceptible TB, −0.18 ± 0.04 (97, 98). This does not mean that M/XDR-TB treated with 6-month, all-oral regimens (e.g. ‘BPaL’ and ‘BPaLM’) becomes non-infectious as fast as drug-susceptible TB because (declining) CFU/ml of viable bacilli has not been confirmed to predict transmission. Growth on artificial media inoculated with processed bacilli from macroscopic sputum specimens is not the same as establishing a new infection in a new host after IRP transit. Treatment may induce functional changes in bacilli, which reduce their ability to establish a new infection before killing them entirely (99). Further research is needed to correlate the pace of decrease with specific measures of infectiousness. Time-to-sputum culture conversion is a surrogate for the effectiveness of treatment, predicting cure versus treatment failure and indicating the possibility of an individual’s infectiousness. A recent meta-analysis of nine MDR-TB treatment studies throughout Eastern Africa found a median sputum culture conversion time to be 61.2 days, consistent with similar studies in Peru (59 days), South Korea (56 days), Dominican Republic (60 days), Latvia (60 days), and Georgia (68 day) (100). In 2024, TB-PRACTECAL showed that BPaLM for MDR-TB-converted sputum cultures to negative in 88% of subjects after 3 months of consistent therapy, similar to prior regimens (101).

The limitations of these data as indirect indicators of human-to-human transmission ultimately lead to variability and imprecision in infection prevention and control policies. Future research should focus on identifying the rates of and risk factors for the transmission of MDR-TB, following initiation of anti-TB treatment coupled with studies of preventing transmission.

Summary and conclusions

Despite advances in transmission science related to respiratory infections after 5 years of SARS-CoV-2 research (as well as ongoing research on TB and other airborne infections), highly visible blanks remain in knowledge needed to understand transmission of airborne pathogens in a manner that will enable targeted, intelligent, and practical efforts to reduce it. To overcome such blanks, we interviewed a dozen experts and searched recent literatures. Identifying salient topics that rose to the top, we reviewed the latest data here on transmission science per se. Knowledge gaps and research recommendations are summarized in bulleted format in the text boxes. The aerobiology and transmission of different viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens differ from each other. One cannot extrapolate from one pathogen to another without comparative evidence. This principle multiplies the gaps and research needs several-fold. Therefore, our review was limited by the limits of comparative research on different pathogens and on different age groups. Furthermore, space did not allow us to include our literature reviews of prevention and control measures, clinical considerations, or behavioral and implementation sciences. In addition to the present review, several reports from a 2017 symposium on Research Needs for Halting Tuberculosis Transmission, as well as first-rate, recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses all lamented the quality of published research, limiting what can be learned from the effort and resources represented by those studies (7–17). The overriding need is for high-quality studies addressing well-informed research questions with methodologically strong study designs, adequate sample sizes, quality data collection systems, and modern multivariable analytic methods. Specific themes are listed below. Acting upon the identified research priorities will provide national and international entities with evidence-based recommendations that will be incorporated into guidelines, standards, and regulation as we work to end TB globally.

Priority research themes

- Defining and measuring infectiousness and transmission in ways that are more precise, more informative, and practical can be seen as a ‘square one’ in terms of knowledge gaps and research priorities.

- The aerobiology of diverse pathogens presents extensive research opportunities.

- Novel sampling and detection methods for monitoring and surveillance, including in real time, are poised for transformative development from research, engineering, clinical, and public health applications.

- Face-masking sampling needs to be thoroughly characterized in terms of its validity, reproducibility, practical applications, and calibration against human infections.

- The same can be said for air sampling methods such as high-flow filters, spore traps, and RASC-like systems with real-world applications outside of laboratories.

- The extent to which bacteria and viruses are expelled by tidal breathing, talking, singing, shouting, laughing, coughing, and other respiratory maneuvers must be better quantified including understanding the variability in emitting these pathogens across the spectrum of disease states – including asymptomatic – and real-world conditions.

- Real-world data are urgently need to evaluate epidemiological models that extrapolate from highly controlled conditions to suggest tidal breathing, and asymptomatic individuals may account for a large proportion of transmitted infection (51, 65, 67).

- The duration of infectiousness of persons with drug-resistant-TB treated with modern 6-month, all-oral regimens needs further evidence.

- Similarly, the impact of comorbidities and associated conditions, including HIV infection, and the effects of young age, sex, and disease characteristics should be explored to better plan and implement infection prevention and control measures.

- Children have been excluded from previous research and must be included in the future.

- The role of super-spreaders in outbreaks, epidemics, and local and global epidemiology begs to be elucidated.

- In general, quantifying and understanding transmission dynamics in diverse real-world settings and calibration of research results from controlled environments against human infections in these settings is an urgent priority.

Once addressed, such advances could transform prevention and control measures for airborne infectious disease, accelerating the decline in morbidity and mortality and preparing humankind for the next, inevitable pandemic. In our companion, co-published article, we focus on advances in airborne infection prevention and control measures that delineate a new set of knowledge gaps and research priorities.

Disclaimers

AK is employed by the World Health Organization. The author alone is responsible for the views in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the World Health Organization.

SA was employed by the U.S. Agency for International Development. The author alone is responsible for the views in this article, and they do not necessarily represent the views, opinions, or policies of USAID or of the US government.

References

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Implementing the end TB strategy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022. |

| 3. | Melsew YA, Doan TN, Gambhir M, Cheng AC, McBryde E, Trauer JM. Risk factors for infectiousness of patients with tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol Infect 2018; 146(3): 345–53. |

| 4. | Jindani A, Doré CJ, Mitchison DA. Bactericidal and sterilizing activities of antituberculosis drugs during the first 14 days. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167(10): 1348–54. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1125OC |

| 5. | Shah M, Dansky Z, Nathavitharana R, Behm H, Brown S, Dov L, et al. National Tuberculosis Coalition of America (NTCA) guidelines for respiratory isolation and restrictions to reduce transmission of pulmonary tuberculosis in community settings. Clin Infect Dis 2024; ciae199. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciae199 |

| 6. | Proano A, Bravard MA, Lopez JW. Dynamics of cough frequency in adults undergoing treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64(9): 1174–81. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix039 |

| 7. | Rouillon A, Perdrizet S, Parrot R. Transmission of tubercle bacilli: the effects of chemotherapy. Tubercle 1976; 57(4): 275–99. |

| 8. | Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, Marks GB. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2013; 41(1): 140–56. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070812 |

| 9. | Becerra MC, Huang CC, Lecca L, Bayona J, Contreras C, Calderon R, et al. Transmissibility and potential for disease progression of drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2019; 367: l5894. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5894 |

| 10. | Walker TM, Monk P, Grace Smith E, Peto TEA. Contact investigations for outbreaks of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: advances through whole genome sequencing. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19(9): 796–802. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12183 |

| 11. | Churchyard G, Kim P, Shah NS, Rustomjee R, Gandhi N, Mathema B, et al. What we know about tuberculosis transmission: an overview. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S629–35. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix362 |

| 12. | Shah NS, Kim P, Kana BD, Rustomjee R. Getting to zero new tuberculosis infections: insights from the National Institutes of Health/US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Workshop on Research Needs for Halting Tuberculosis Transmission. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S627–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix311 |

| 13. | Auld SC, Kasmar AG, Dowdy DW, Mathema B, Gandhi NR, Churchyard GJ, et al. Research roadmap for tuberculosis transmission science: where do we go from here and how will we know when we’re there? J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S662–8. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix353 |

| 14. | Mathema B, Andrews JR, Cohen T, Borgdorff MW, Behr M, Glynn JR, et al. Drivers of tuberculosis transmission. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S644–53. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix354 |

| 15. | Dowdy DW, Grant AD, Dheda K, Nardell E, Fielding K, Moore DAJ. Designing and evaluating interventions to halt the transmission of tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S654–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix320 |

| 16. | Turner RD, Chiu C, Churchyard GJ, Esmail H, Lewinson DM, Gandhi NR, et al. Tuberculosis infectiousness and host susceptibility. J Infect Dis 2017; 216(suppl_6): S636–43. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix361 |

| 17. | World Health Organization. Global technical consultation report on proposed terminology for pathogens that transmit through the air. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. |

| 18. | Fox GJ, Redwood L, Chang V, Ho J. The effectiveness of individual and environmental infection control measures in reducing the transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 72(1): ciaa719. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa719 |

| 19. | Karat AS, Gregg M, Barton HE, Calderon M, Ellis J, Falconer J, et al. Evidence for the use of triage, respiratory isolation, and effective treatment to reduce the transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis in healthcare settings: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 72(1): ciaa720. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa720 |

| 20. | Goko C, Forster E, Mason M, Zimmerman PA. Effectiveness of fit testing versus fit checking for healthcare workers respiratory protective equipment: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Sci 2023; 10(4): 568–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.09.011 |

| 21. | Ferrari S, Blázquez T, Cardelli R, Puglisi G, Suárez R, Mazzarella L. Ventilation strategies to reduce airborne transmission of viruses in classrooms: a systematic review of scientific literature. Build Environ 2022; 222: 109366. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109366 |

| 22. | Greenhalgh T, MacIntyre CR, Baker MG, Bhattacharjee S, Chughtal AA, Fisman D, et al. Masks and respirators for prevention of respiratory infections: a state of the science review. Clin Microbiol Rev 2024; 37(2): e0012423. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00124-23 |

| 23. | Dinkele R. Capture and visualization of live Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli from tuberculosis patient bioaerosols. PLoS Pathog 2021; 17: e1009262. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009262 |

| 24. | Domino S. A case study on pathogen transport, deposition, evaporation and transmission: linking high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics simulations to probability of infection. Int J Comput Fluid Dyn 2021; 35(9): 743–57. doi: 10.1080/10618562.2021.1905801 |

| 25. | Peng S, Chen Q, Liu E. The role of computational fluid dynamics tools on investigation of pathogen transmission: prevention and control. Sci Total Environ 2020; 746(1): 142090. |

| 26. | Mikszewski A, Stabile L, Buonanno G, Morawska L. The airborne contagiousness of respiratory viruses: a comparative analysis and implications for mitigation. Geosci Front 2022; 13(6): 101285. doi: 10.1016/j.gsf.2021.101285 |

| 27. | Oswin H, Haddrell A, Otero-Fernandez M. The dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 infectivity with changes in aerosol microenvironment. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2022; 119(27): e2200109119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2200109119 |

| 28. | Ahlawat A, Mishra SK, Herrmann H, Rajeev P, Gupta T, Goel V, et al. Impact of chemical properties of human respiratory droplets and aerosol particles on airborne viruses’ viability and indoor transmission. Viruses 2022; 14(7): 1497. doi: 10.3390/v14071497 |

| 29. | Toman K. Tuberculosis case-finding and chemotherapy. 1st ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1979. |

| 30. | Acuna-Villaorduna C, White LF, Fennelly KP, Jones-Lopez EC. Tuberculosis transmission: sputum vs aerosols. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16(7): 770–71. |

| 31. | Jones-Lopez EC, Namugga O, Mumbowa F, Ssebidandi M, Mbabazi O, Moine S. Cough aerosols of Mycobacterium tuberculosis predict new infection: a household contact study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187(9): 1007–15. |

| 32. | Wood R. Real-time investigation of tuberculosis transmission: developing the respiratory aerosol sampling chamber (RASC). PLoS One 2016; 11: 0146658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146658 |

| 33. | Middelkoop K, Koch AS, Hoosen Z, Bryden W, Call C, Seldon R. Environmental air sampling for detection and quantification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical settings: proof of concept. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023; 44(5): 774–9. |

| 34. | Hassane-Harouna S, Braet SM, Decroo T, Camara LM, Delamou A, de Bock S, et al. Face mask sampling (FMS) for tuberculosis shows lower diagnostic sensitivity than sputum sampling in Guinea. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2023; 22(1): 81. doi: 10.1186/s12941-023-00633-8 |

| 35. | Williams CM, Muhammad AK, Sambou B, Bojang A, Jobe A, Daffeh G, et al. Exhaled Mycobacterium tuberculosis predicts incident infection in household contacts. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76(3): e957–64. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac455 |

| 36. | Williams CM, Pan D, Decker J, Wisniewska A, Fletcher E, Sze S, et al. Exhaled SARS-CoV-2 quantified by face-mask sampling in hospitalised patients with COVID-19. J Infect 2021; 82(6): 253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.03.018 |

| 37. | Nyaruaba R, Xiong J, Mwaliko C, Wang N, Kibii BJ, Yu J, et al. Development and evaluation of a single dye duplex droplet digital PCR assay for the rapid detection and quantification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microorganisms 2020; 8(5): 701. |

| 38. | Cho SM, Shin S, Kim Y, Song W, Hong SG, Jeong SH. A novel approach for tuberculosis diagnosis using exosomal DNA and droplet digital PCR. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26(7): 942e.1–5. |

| 39. | Ma J, Jiang G, Ma Q, Wang H, Du M, Wang C. Rapid detection of airborne protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis using a biosensor detection system. Analyst 2022; 147(4): 614–24. |

| 40. | Patterson B. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli in bio-aerosols from untreated TB patients. Gates Open Res 2018; 1: 11. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.12758.2 |

| 41. | Cheng J, An Y, Wang Q, Chen Z, Tong Y. Visual detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in exhaled breath using N95 enrichment respirator, RPA, and lateral flow assay. Talanta 2025; 286: 127490. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2024.127490 |

| 42. | Huffman J, Perring A, Savage N, Clot B, Crouzy B, Tummon F, et al. Real-time sensing of bioaerosols: review and current perspectives. Aerosol Sci Technol 2020; 54(5): 465–95. |

| 43. | Kabir E, Azzouz A, Raza N, Bhardwaj SK, Kim KH, Tabatabaei M, et al. Recent advances in monitoring, sampling, and sensing techniquesfor bioaerosols in the atmosphere. ACS Sens 2020; 5(5): 1254–67. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.9b02585 |

| 44. | An T, Liang Z, Chen Z, Li G. Recent progress in online detection methods of bioaerosols. Fundam Res 2024; 4(3): 442–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fmre.2023.05.012 |

| 45. | McNerney R. Field test of a novel detection device for Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen in cough. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-161 |

| 46. | Williams CM. Face mask sampling for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in expelled aerosols. PLoS One 2014; 9: 104921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104921 |

| 47. | Williams CM, Abdulwhhab M, Birring SS, De Kock E, Garton N, Townsend E, et al. Exhaled Mycobacterium tuberculosis output and detection of subclinical disease by face-mask sampling: prospective observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20(5): 607–17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30707-8 |

| 48. | Tedeschini E, Pasqualini S, Emiliani C, Marini E, Valecchi A, Laoreti C, et al. Monitoring of indoor bioaerosol for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in different hospital settings. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1169073. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1169073 |

| 49. | Li S. Assessing airborne transmission risks in COVID-19 hospitals by systematically monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in the air. Microbiol Spectr 2023; 11: 0109923. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.01099-23 |

| 50. | Tellier R, Li Y, Cowling BJ, Tang JW. Recognition of aerosol transmission of infectious agents: a commentary. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19(1): 101. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3707-y |

| 51. | Kendall EA, Shrestha S, Dowdy DW. The epidemiological importance of subclinical tuberculosis. a critical reappraisal. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021; 203(2): 168–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2394PP |

| 52. | Zaidi SMA, Coussens AK, Seddon JA. Beyond latent and active tuberculosis: scoping review of conceptual frameworks. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 66: 102332. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102332 |

| 53. | Coussens AK, Zaidi SMA, Allwood BW. Classification of early tuberculosis states to guide research for improved care and prevention: an international Delphi consensus exercise. Lancet Respir Med 2024; 12(6): 484–98. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(24)00028-6 |

| 54. | Frascella B, Richards AS, Sossen B. Subclinical tuberculosis disease-a review and analysis of prevalence surveys to inform definitions, burden, associations, and screening methodology. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73(3): 830–41. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1402 |

| 55. | Stuck L, Klinkenberg E, Abdelgadir Ali N. Prevalence of subclinical pulmonary tuberculosis in adults in community settings: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2024; 24(7): 726–36. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(24)00011-2 |

| 56. | Teo AKJ, MacLean EL, Fox GJ. Subclinical tuberculosis: a meta-analysis of prevalence and scoping review of definitions, prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir Rev 2024; 33(172): 230208. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0208-2023. |

| 57. | WHO. Report of the WHO consultation on asymptomatic tuberculosis, Geneva, Switzerland, 14–15 October 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. |

| 58. | Tan Q, Huang CC, Becerra MC. Chest Radiograph Screening for Detecting Subclinical Tuberculosis in Asymptomatic Household Contacts. Emerg Infect Dis 2024; 30(6): 1115–24. doi: 10.3201/eid3006.231699 |

| 59. | Coleman M, Martinez L, Theron G, Wood R, Marais B. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission in high-incidence settings. Pathogens 2022; 11(11): 1228. doi: 10.3390/pathogens11111228 |

| 60. | Nguyen HV, Tiemersma E, Nguyen NV, Nguyen HB, Cobelens F. Disease transmission by patients with subclinical tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76(11): 2000–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad027 |

| 61. | Ziemele B, Ranka R, Ozere I. Pediatric and adolescent tuberculosis in Latvia, 2011–2014: case detection, diagnosis and treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017; 21(6): 637–45. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0270 |

| 62. | Fritschi N, Wind A, Hammer J, Ritz N. Subclinical tuberculosis in children: diagnostic strategies for identification reported in a 6-year national prospective surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 74(4): 678–84. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab708 |

| 63. | Emery JC, Dodd PJ, Banu S. Estimating the contribution of subclinical tuberculosis disease to transmission: an individual patient data analysis from prevalence surveys. Elife 2023; 12: 82469. doi: 10.7554/eLife.82469. |

| 64. | Verdier J, de Vlas SJ, Kidgell-Koppelaar I, Richardus JH. Risk factors for tuberculosis in contact investigations in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Infect Dis Rep 2012; 4(2): e26. doi: 10.4081/idr.2012.e26 |

| 65. | Dinkele R. Aerosolization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by tidal breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022; 206: 206–16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202110-2378OC |

| 66. | Shaikh A, Sriraman K, Vaswani S, Oswal V, Mistry N. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA in bioaerosols from pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Int J Infect Dis 2019; 86: 5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.06.006 |

| 67. | Dinkele R, Gessner S, Patterson B, McKerry A, Hoosen Z, Vazi A, et al. Persistent Mycobacterium tuberculosis bioaerosol release in a tuberculosis-endemic setting. medRxiv 2024; 27(9): 110731. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110731. |

| 68. | Stadnytskyi V, Anfinrud P, Bax A. Breathing, speaking, coughing or sneezing: what drives transmission of SARS-CoV-2? J Intern Med 2021; 290(5): 1010–27. doi: 10.1111/joim.13326 |

| 69. | Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A, Anfinrud P. The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117(22): 11875–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006874117 |

| 70. | Anfinrud P, Stadnytskyi V, Bax CE, Bax A. Visualizing speech-generated oral fluid droplets with laser light scattering. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(21): 2061–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007800 |

| 71. | Bax A, Bax CE, Stadnytskyi V, Anfinrud P. SARS-CoV-2 transmission via speech-generated respiratory droplets. Lancet Infect Dis 2021; 21(3): 318. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30726-X |

| 72. | Gharpure R, Sami S, Vostok J, Johnson H, Hall N, Foreman A, et al. Multistate outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including vaccine breakthrough infections, associated with large public gatherings, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 2022; 28(1): 35–43. doi: 10.3201/eid2801.212220 |

| 73. | Sultan L, Nyka W, Mills C, O’Grady F, Wells W. Tuberculosis disseminators. Am Rev Resp Dis 1960; 82(22): 358–69. |

| 74. | Escombe AR, Oeser C, Gilman RH, Navincopa M, Ticona E, Martinez C, et al. The detection of airborne transmission of tuberculosis from HIV-infected patients, using an in vivo air sampling model. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(10): 1349–57. doi: 10.1086/515397 |

| 75. | Jones-López EC, Acuña-Villaorduña C, Ssebidandi M, Gaeddert M, Kubiak RW, Ayakaka I, et al. Cough aerosols of mycobacterium tuberculosis in the prediction of incident tuberculosis disease in household contacts. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(1): 10–20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw199 |

| 76. | Smith J, Oeltmann J, Hill A, Tobias JL, Boyd R, Click ES, et al. Characterizing tuberculosis transmission dynamics in high-burden urban and rural settings. Nat Sci Rep 2022; 12(1): 6780. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-10488-2 |

| 77. | Smith J, Cohen T, Dowdy D, Shrestha S, Gandhi N, Hill A. Quantifying mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission dynamics across global settings: a systematic analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2023; 192(1): 133–45. |

| 78. | McKee CD, Yu EX, Garcia A, Jackson J, Koyuncu A, Rose S, et al. Superspreading of SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis of event attack rates and individual transmission patterns. Epidemiol Infect 2024; 152: e121. doi: 10.1017/S0950268824000955 |

| 79. | Wang L. Characterization of aerosol plumes from singing and playing wind instruments associated with the risk of airborne virus transmission. Indoor Air 2022; 32: 13064. doi: 10.1111/ina.13064 |

| 80. | Wegehaupt O, Endo A, Vassall A. Superspreading, overdispersion and their implications in the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. BMC Public Health 2023; 23(1): 1003. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15915-1 |

| 81. | Noble R. Infectiousness of pulmonary tuberculosis after starting chemotherapy. Am J Infect Control 1981; 9: 6–10. |

| 82. | Riley RL, Mills CC, Nyka W. Aerial dissemination of pulmonary tuberculosis. A two-year study of contagion in a tuberculosis ward. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142(1): 3–14. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117542 |

| 83. | Calderwood CJ, Wilson JP, Fielding KL. Dynamics of sputum conversion during effective tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021; 18(4): 1003566. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003566 |

| 84. | Loiseau C, Windels E, Gygli S. The relative transmission fitness of multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a drug resistance hotspot. Nat Commun 2023; 14(1): 1988. |

| 85. | Burgos M, DeRiemer K, Small PM, Hopewell PC, Daley CL. Effect of drug resistance on the generation of secondary cases of tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2003; 188(12): 1878–84. doi: 10.1086/379895 |

| 86. | Gagneux S. Fitness cost of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2009; 15 Suppl 1: 66–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02685.x |

| 87. | Shah NS, Yuen CM, Heo M, Tolman AW, Becerra MC. Yield of contact investigations in households of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(3): 381–91. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit643 |

| 88. | Grandjean L, Gilman RH, Martin L. Transmission of multidrug-resistant and drug-susceptible tuberculosis within households: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2015; 12(6): 1001843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001843 |

| 89. | Dharmadhikari AS, Basaraba RJ, Van Der Walt ML, Weyer K, Mphalele M, Venter K, et al. Natural infection of guinea pigs exposed to patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis. Tuberculosis 2011; 91(4): 329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.03.002 |

| 90. | Dharmadhikari AS, Mphahlele M, Venter K, Stoltz A, Mathebula R, Masotla T, et al. Rapid impact of effective treatment on transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2014; 18(9): 1019–25. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0834 |

| 91. | Zainabadi K, Vilbrun SC, Mathurin LD, Walsh KF, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW, et al. A bedaquiline, pyrazinamide, levofloxacin, linezolid, and clofazimine second-line regimen for tuberculosis displays similar early bactericidal activity as the standard rifampin-based first-line regimen. J Infect Dis 2024; 230(2): e447–56. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiad564 |

| 92. | Fox GJ, Schaaf HS, Mandalakas A, Chiappini E, Zumla A, Marais BJ. Preventing the spread of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and protecting contacts of infectious cases. Clin Microbiol Infect 2017; 23(3): 147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.08.024 |

| 93. | Conradie F, Diacon AH, Ngubane N, Howell P, Everitt D, Crook A, et al. Treatment of highly drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(10): 893–902. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901814 |

| 94. | Stoltz A, Nathavitharana R, de Kock E, Ueckermann V, Jensen P, Mendel CM, et al. Estimating the Early Transmission Inhibition of new treatment regimens for drug-resistant tuberculosis. J Infect Dis 2025; 232(1): jiaf005. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaf005 |

| 95. | Koele SE, Phillips PPJ, Upton CM. Early bactericidal activity studies for pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review of methodological aspects. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2023; 61(5): 106775. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2023.106775 |

| 96. | Koul A, Vranckx L, Dhar N. Delayed bactericidal response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to bedaquiline involves remodelling of bacterial metabolism. Nat Commun Feb 2014; 5: 3369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4369 |

| 97. | Diacon AH, Dawson R, Du Bois J, Narunsky K, Venter A, Donald PR, et al. Phase II dose-ranging trial of the early bactericidal activity of PA-824. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56(6): 3027–31. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06125-11 |

| 98. | Diacon AH, Dawson R, Von Groote-Bidlingmaier F, Symons G, Venter A, Donald PR, et al. 14-day bactericidal activity of PA-824, bedaquiline, pyrazinamide, and moxifloxacin combinations: a randomised trial. Lancet 2012; 380(9846): 986–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61080-0 |

| 99. | Poonawala H, Zhang Y, Kuchibhotla S, Green AG, Cirillo DM, Di Marco F, et al. Transcriptomic responses to antibiotic exposure in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2024; 68(5): e0118523. doi: 10.1128/aac.01185-23 |

| 100. | Assemie MA, Alene M, Petrucka P, Leshargie CT, Ketema DB. Time to sputum culture conversion and its associated factors among multidrug-resistant TB patients East Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 98: 230–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.029 |

| 101. | Nyang’wa BT, Berry C, Kazounis E, Motta I, Parpieva N, Tigay Z, et al. A 24-week, all-oral regimen for rifampin-resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med 2022; 387(25): 2331–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2117166 |