ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

The role of povidone-iodine versus saline irrigation in preventing surgical site infections in high body mass index patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Thiago de Albuquerque Farias Camarotti1, Victoria Zecchin Ferrara2, Vitória Ritter Maldaner3, Augusto Graziani e Sousa4, Enrico Prajiante Bertolino5, Maria Tereza Camarotti6 and Marcelo Averbach7

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Pernambuco, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil; 2Faculty of Medicine and Surgery, University of Padua, Padua, Veneto, Italy; 3University of Vale do Itajaí, Itajaí, Santa Catarina, Brazil; 4Anápolis University Center, Anápolis, Goiás, Brazil; 5State University of Maringá, Paraná, Brazil; 6Pernambuco’s Health College, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil; 7Sírio-Libanês Institute of Education and Research, São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Abstract

Background: Surgical site infections (SSIs) are common complications post-surgery, associated with increased morbidity, healthcare costs, and prolonged recovery. High body mass index (BMI) patients face an elevated risk due to impaired wound healing and systemic inflammation. Wound irrigation with Polyvinylpyrrolidone Iodine (PVP-I) or normal saline (NS) is commonly used, but their comparative effectiveness in high-BMI patients remains unclear.

Objective: The study aims to evaluate whether PVP-I is more effective than NS in reducing SSIs in high-BMI surgical patients.

Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods: PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched up to December 2024 for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies comparing PVP-I and NS for SSI prevention in high-BMI patients. Risk of bias was assessed using ROB 2 for RCTs and ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were pooled using a random-effects model in R Studio 4.4.2.

Results: Four studies with 604 high-BMI patients were included. The pooled analysis showed a decreased SSI rate in the PVP-I group, though not statistically significant (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.29–1.13; P = 0.11; I² = 39.4%). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of findings.

Discussion: The effectiveness of PVP-I may depend on factors like surgery type and the patient’s clinical status. Although irrigation may have a protective effect, effective preventive strategies should consider the antiseptic agent and perioperative patient optimization.

Conclusion: This meta-analysis suggests that PVP-I irrigation may reduce SSIs in high-BMI patients, though statistical significance was not reached. Further research is needed to confirm its potential benefits.

Keywords: surgical site infection; povidone-iodine; high BMI; normal saline; wound irrigation

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2025, 21: 23837 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v21.23837

Copyright: © 2025 Thiago de Albuquerque Farias Camarotti et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 10 March 2025; Revised: 13 May 2025; Accepted: 4 June 2025; Published: 10 September 2025

To access the supplementary file, please visit the article landing page

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest and no funding.

*Thiago de Albuquerque Farias Camarotti, Tv. Jackson Pollock Santo Amaro, Recife PE, 52171-011, Brazil

Surgical site infections (SSIs) represent the most common postoperative complications. These infections, classified as superficial, deep, or organ space, occur within 30 days of surgery or up to a year in cases involving implanted hardware (1, 2). SSIs contribute to higher morbidity and mortality rates, increased healthcare costs, and a decline in patients’ quality of life (3, 4).

Patients with a high body mass index (BMI) are particularly vulnerable to SSIs due to factors such as impaired wound healing, excess adipose tissue, and systemic inflammation. BMI does not directly assess body fat but is widely used for classification. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adults are categorized as normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m²), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²) (5). While other methods such as bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) provide more precise body fat percentage (%BF) measurements, they are costly and less accessible. Some studies define obesity using %BF thresholds (25% for males, 35% for females), but there is no universally accepted %BF standard for overweight and obesity (6). Furthermore, tools that accurately measure adiposity are expensive and not widely accessible. Given its practicality and widespread use in clinical and epidemiological research, BMI remains the primary tool for assessing adiposity and evaluating its correlation with SSI risk.

Due to the challenges in preventing SSIs, various perioperative strategies have been explored to reduce their incidence and enhance surgical outcomes. These include optimizing nutrition, ensuring adequate perioperative oxygenation, refining surgical techniques, using proper wound coverings, maintaining strict sterile protocols, and administering prophylactic antibiotics (7, 8).

The risk of SSIs can be minimized through prophylactic intraoperative incisional wound irrigation (pIOWI), which helps remove debris, metabolic waste, and exudate that may contain microbes before wound closure (9). Various irrigation solutions and application methods are used in practice: Polyvinylpyrrolidone Iodine (PVP-I), a broad-spectrum antiseptic with strong antimicrobial properties, is commonly utilized for skin preparation and wound irrigation due to its effectiveness in reducing bacterial load and preventing infections; in contrast, normal saline (NS) is frequently used as a mechanical cleanser but lacks inherent antimicrobial activity. Swaminathan et al. suggest that PVP-I may lower SSI rates, leading to the belief that it is more effective than NS (10). However, there is insufficient evidence to definitively support or refute the use of NS for incisional wound irrigation (11). Some studies have not demonstrated a clear advantage of PVP-I over other solutions, including NS (12, 13).

Additionally, current clinical guidelines vary and provide inconsistent recommendations (14–16). The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (17) and the WHO (15, 18) recommend irrigation with PVP-I; however, both guidelines are conditional and based on low-quality evidence. Additionally, while the WHO advises against using antibiotic solutions, a Cochrane Review suggests that antibacterial irrigation may be more effective than non-antibacterial alternatives (19). As a result, patients may receive inconsistent care, highlighting the urgent need for more comparative data on PVP-I versus NS irrigation.

A recent network meta-analysis by Thom et al. (20) found that antibiotic and antiseptic solutions were associated with the lowest odds of SSIs compared to no irrigation or non-antibacterial irrigation. However, this analysis has limitations, as it combines randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on both incisional wound irrigation and intracavity lavage, which are distinct interventions with different objectives.

Another meta-analysis by Groenen et al. (21) examined the effectiveness of various prophylactic intraoperative incisional wound irrigation methods for preventing SSIs across different types of surgery but did not specifically focus on obese patients. Some studies have reported an increased BMI as a risk factor for SSIs (13, 22). Therefore, the comparative effectiveness of these irrigation solutions in high-BMI patients remains an area of ongoing investigation.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs and observational studies to determine whether PVP-I is more effective than NS in reducing SSIs in surgical patients with high BMI.

Methods

PICO process and search strategy

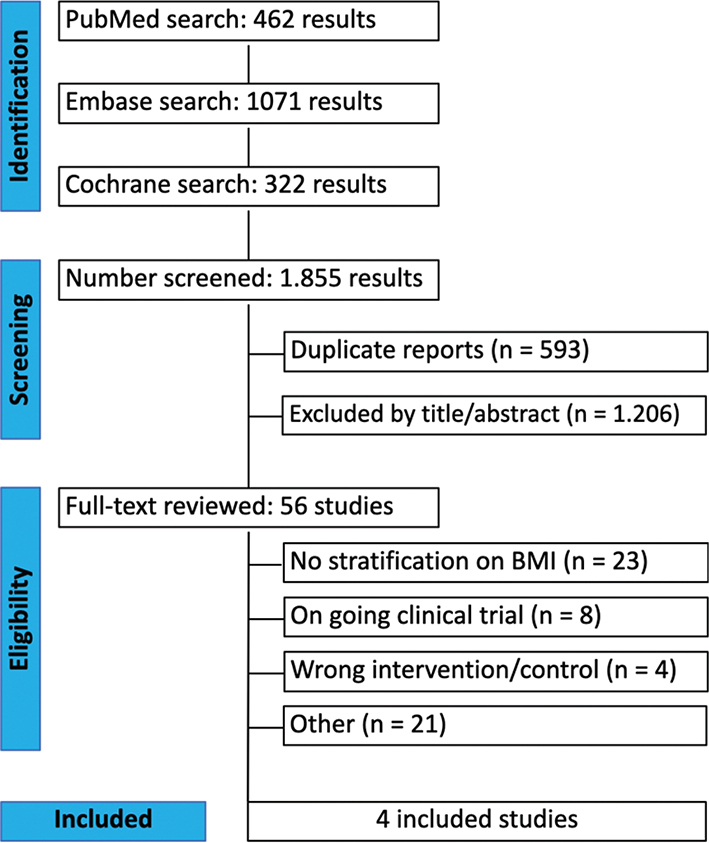

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed and reported under the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (23) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement guidelines (24). An extensive search of Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane software was conducted from inception to 19 December 2024, for which we utilized different search strategies (eMethods in the supplementary material). A database search was performed by the first author (T.A.F.C.).

The search retrieved RCTs and observational studies comparing PVP-I to NS in the prevention of SSIs in patients with high BMI. All identified articles were imported into Zotero for the organization. Duplicate entries were first removed, and two authors (V.Z.F. and T.A.F.C.) independently screened the titles and abstracts using the software Rayyan. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of the remaining articles were then carefully reviewed based on the eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between the two authors (V.Z.F. and T.A.F.C.).

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that met the following eligibility criteria: (1) RCTs and observational studies, (2) comparisons between PVP-I and NS, (3) reporting at least one relevant outcome, and (4) involving patients with a high BMI or a subgroup of high BMI patients within the trial.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) conference abstracts, editorials, review articles, or animal studies, (2) lack of a placebo control group, (3) overlapping populations, or (4) no specification regarding BMI.

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors (V.R.M and T.A.F.C.) independently extracted the data, and any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Data from each study were collected using a standardized form in Microsoft Excel, capturing key details such as the authors, year of publication, sample size, intervention specifics, follow-up duration, and baseline participant characteristics, which is summarized in Table 1. Considering the small subgroup, the data extraction focused on the sole outcome of SSI.

| Study | Design | Follow-up | Patients PVP-I/NSS | Female PVP-I/NS | Age† PVP-I/NS | BMI kg/m² Threshold | High BMI N (%) | BMI† kg/m² PVP-I/NS | Current smoking PVP-I/NS | Diabetes PVP-I/NS | Bleeding† (ml)PVP-I/NS | ASA ≥ 3 PVP-I/NS |

| Takeda et al. | RCT | 30 days | 347/350 | 138/129 | 60 ± 53.6/ 60.7 ± 53.6 | ≥25 | 179 (25.68) | 27.9 ± 25.46/ 27.53 ± 23.67 | 66/62 | 55/70 | 10.97 ± 1.41/ 12.95 ± 2.11 | 37/49 |

| Ali et al. | RCT | 30 days | 90/90 | 40/37 | 36 ± 15.1/ 37.6 ± 14.9 | >25 | 59 (32.77) | 22.5 ± 3.9/ 23.6 ± 3.9 | - | 0/0 | - | - |

| Zhao et al. | RCT | 30 days | 166/167 | 52/61 | 59.14 ± 9.98/ 59.28 ± 10.93 | ≥24 | 121 (36.33) | - | 71/79 | 11/13 | 115.94 ± 78.03/ 10.18 ± 75.89 | 25/40 |

| Carballo Cuello et al. | Retrospective Cohort | 2, 4 and 12 weeks | 144/134 | 55/65 | 54.9 ± 17.45/ 58.2 ± 14.8 | ≥25 | 245 (88.12) | 31.33 ± 6.74/ 30.67 ± 5.25 | 5/8 | 79/60 | 225 ± 56.16/ 216.67 ± 74.94 | - |

| †Mean ± standard deviation. | ||||||||||||

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration tool ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) (25) and RoB 2 (Risk-of-Bias tool for Randomized Trials) (26) were used for the quality assessment of the included studies. Through the ROBINS-I tool, studies are scored as low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias, and through the RoB 2 studies they are scored as low, with some concerns, and high risk of bias. Two independent authors (A.G. and E.B.) conducted the assessment. Disagreements were resolved by consensus between the authors. The Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis) tool was used for generating the figures describing bias assessment.

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were pooled using the Inverse Variance method. Random effects were used in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (23). The heterogeneity estimator method used was Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML). Heterogeneity was assessed with Cochran’s Q, I2, and Τau2 measures. Thresholds for these values were considered as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity with values of 0–49%, 50–75%, and greater than or equal to 75%, respectively. R Studio (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) Version 4.4.2 was used for the statistical analysis. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the leave-one-out strategy.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

An initial search yielded 1,855 articles. After removing 593 duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 56 articles were selected for a full-text analysis. Among them, 52 were excluded according to the following exclusion criteria: 23 had no stratification on BMI: eight were ongoing RCTs; four had wrong intervention/control; and 21 for other reasons (Fig. 1). Ultimately, four articles comprising three RCTs and one retrospective cohort, with a total of 604 patients, met the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. Of these patients, 296 (49%) received PVP-I while 308 (51,1%) received Normal Saline Solution (NSS). Study characteristics are reported in Table 1.The BMI threshold used in the work of Zhao et al. was 24 kg/m², the other studies used a value of 25 kg/m².

Pooled analysis of all studies

As illustrated in Fig. 2, the use of PVP-I in high BMI patients has shown a lower SSI rate, although not showing statistical significance (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.29–1.13; P = 0.11; I² = 39.4%).

Fig. 2. Forest plot for the outcome of surgical site infection.

Risk of bias assessment

Assessments of the risk of methodological bias were presented visually, in the supplementary data, in Fig. S1 for RCTs and Fig. S2for observational studies.

Sensitivity analysis

Due to the heterogeneity, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was performed and presented in the supplementary data. Results remained consistent after omitting individual studies (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of four studies comprising 604 patients, we evaluated the incidence of SSI in high BMI patients undergoing surgery, comparing intraoperative incisional wound irrigation with PVP-I versus normal NS. Our pooled analysis did not reveal a statistical significance, although it showed a lower SSI rate in the PVP-I group, suggesting a potential benefit of PVP-I irrigation in reducing postoperative infections in this patient population. Although PVP-I is commonly used for its broad antimicrobial activity, it may carry some risks. For example, a temporary rise in serum iodine levels has been observed in an elderly patient during surgical wound irrigation, and transient thyroid suppression has been noted in preterm infants. While clinical trials in adults have not shown serious toxicity, the possibility of harm remains in certain individuals risks that are not associated with the use of NS (13).

A meta-analysis conducted by Abdallah et al. (27) demonstrated a significant correlation between elevated BMI and the propensity for SSIs following spinal surgery. Specifically, a 5-unit increase in BMI was associated with a 21% higher risk of developing SSIs after spinal procedures, even after adjusting for confounding factors such as diabetes. These findings highlight the necessity of incorporating BMI into preoperative assessments and reinforce the imperative for strategies to mitigate infection risks in patients with increased BMI.

While several studies confirm the association between high BMI and increased SSI risk, evidence on the effectiveness of preventive strategies remains limited. To better understand this issue, an analysis of the studies by Cuello et al. (22) and Zhao et al. (13) reveals complementary perspectives on this relationship.

Cuello et al. (22) investigated SSIs in patients undergoing posterior lumbar instrumentation and reported that all observed cases occurred in individuals classified as overweight (25–25.9) or obese (≥30), with relative risk (RR) increases of 20 and 49%, respectively. Similarly, Zhao et al. (13), utilizing multivariate logistic regression analysis, identified elevated BMI and postoperative complications as independent risk factors for SSI. However, subgroup analysis of patients with high BMI demonstrated no statistically significant difference in SSI rates between the PVP-I and NS irrigation cohorts. These findings suggest that while intraoperative irrigation may contribute to SSI risk reduction under specific clinical conditions, infection susceptibility is multifactorial, influenced by patient-specific and procedural determinants.

This meta-analysis corroborates previous findings, indicating a trend toward the efficacy of PVP-I irrigation in SSI prophylaxis. However, the included studies did not demonstrate statistically significant reductions in SSI incidence among patients with elevated BMI. These findings suggest that while PVP-I irrigation may confer a protective effect against SSIs, its efficacy is modulated by variables such as the specific surgical intervention and the patient’s overall clinical status. Therefore, the formulation of robust preventive strategies necessitates a multifactorial approach, integrating the selection of an optimal antiseptic agent with the perioperative optimization of patient health parameters. Moreover, subgroup analysis demonstrated that the exclusion of the study by Cuello et al. (22) eliminated heterogeneity, likely attributable to the fact that the remaining studies were RCTs. Additionally, Cuello et al. (22) was the only study with an extended follow-up period, which may have contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

This study has limitations that should be acknowledged. Low heterogeneity was observed in the SSI risk analysis, likely due to variations in study design and follow-up durations, which ranged from 30 days to 12 weeks. However, sensitivity analyses, including a leave-one-out approach, confirmed the robustness of the findings. The small number of included studies limited statistical power and the generalizability of findings.

Future research should include a larger number of high-quality studies with standardized methodologies and more uniform follow-up periods to enhance the reliability of findings and provide more definitive insights.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis suggests a potential role for PVP-I irrigation in SSI prevention among patients with high BMI. However, given the lack of statistically significant findings in our pooled analysis, further large-scale, high-quality RCTs with homogeneous populations are necessary to validate these observations. Future research should also assess the long-term safety, efficacy, and broader clinical applicability of PVP-I irrigation in this patient cohort.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Makoto Takeda for providing data for their pooled analysis.

References

| 1. | Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 1999 Apr; 27(2): 97–132; quiz 133–4; discussion 96. doi: 10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70088-X |

| 2. | Gillespie BM, Harbeck E, Rattray M, Liang R, Walker R, Latimer S, et al. Worldwide incidence of surgical site infections in general surgical patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 488,594 patients. Int J Surg Lond Engl 2021 Nov; 95: 106136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.106136 |

| 3. | Surveillance of surgical site infections and prevention indicators in European hospitals – HAISSI protocol [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surveillance-surgical-site-infections-and-prevention-indicators-european [cited 27 February 2025]. |

| 4. | Badia JM, Casey AL, Petrosillo N, Hudson PM, Mitchell SA, Crosby C. Impact of surgical site infection on healthcare costs and patient outcomes: a systematic review in six European countries. J Hosp Infect 2017 May; 96(1): 1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2017.03.004 |

| 5. | World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 2000; 894: i–xii, 1–253. |

| 6. | Ho-Pham LT, Campbell LV, Nguyen TV. More on body fat cutoff points. Mayo Clin Proc 2011 Jun; 86(6): 584. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0097 |

| 7. | Watters WC, Baisden J, Bono CM, Heggeness MH, Resnick DK, Shaffer WO, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in spine surgery: an evidence-based clinical guideline for the use of prophylactic antibiotics in spine surgery. Spine J Off J North Am Spine Soc 2009 Feb; 9(2): 142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2008.05.008 |

| 8. | Schuster JM, Rechtine G, Norvell DC, Dettori JR. The influence of perioperative risk factors and therapeutic interventions on infection rates after spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine 2010 Apr 20; 35(9 Suppl): S125–137. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d8342c |

| 9. | Papadakis M. Wound irrigation for preventing surgical site infections. World J Methodol 2021 Jul 20; 11(4): 222–7. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v11.i4.222 |

| 10. | Swaminathan C, Toh WH, Mohamed A, Nour HM, Baig M, Sajid M. Comparing the efficacy of povidone-iodine versus normal saline in laparotomy wound irrigation to prevent surgical site infections: a meta-analysis. Cureus. 15(12): e49853. |

| 11. | Ambe PC, Rombey T, Rembe JD, Dörner J, Zirngibl H, Pieper D. The role of saline irrigation prior to wound closure in the reduction of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Saf Surg 2020 Dec 22; 14(1): 47. doi: 10.1186/s13037-020-00274-2 |

| 12. | Karuserci Ö, Balat Ö. Subcutaneous rifampicin versus povidone-iodine for the prevention of incisional surgical site infections following gynecologic oncology surgery – a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ginekol Pol 2020 Sep 30; 91: 513–8. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2020.0134 |

| 13. | Zhao LY, Zhang WH, Liu K, Chen XL, Yang K, Chen XZ, et al. Comparing the efficacy of povidone-iodine and normal saline in incisional wound irrigation to prevent superficial surgical site infection: a randomized clinical trial in gastric surgery. J Hosp Infect 2023 Jan 1; 131: 99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2022.10.005 |

| 14. | Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg 2017 Aug 1; 152(8): 784–91. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904 |

| 15. | Global guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection [Internet]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550475 [cited 27 February 2025]. |

| 16. | Surgical site infections: prevention and treatment [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2020. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542473/ [cited 27 February 2025]. |

| 17. | Leaper D, Rochon M, Pinkney T, Edmiston CE. Guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infection: an update from NICE. Infect Prev Pract 2019 Nov 22; 1(3–4): 100026. doi: 10.1016/j.infpip.2019.100026 |

| 18. | Allegranzi B, Zayed B, Bischoff P, Kubilay NZ, de Jonge S, de Vries F, et al. New WHO recommendations on intraoperative and postoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis 2016 Dec 1; 16(12): e288–303. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30402-9 |

| 19. | Norman G, Atkinson RA, Smith TA, Rowlands C, Rithalia AD, Crosbie EJ, et al. Intracavity lavage and wound irrigation for prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017 Oct 30; 10(10): CD012234. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012234.pub2 |

| 20. | Thom H, Norman G, Welton NJ, Crosbie EJ, Blazeby J, Dumville JC. Intra-cavity lavage and wound irrigation for prevention of surgical site infection: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Surg Infect 2021 Mar; 22(2): 144–67. doi: 10.1089/sur.2019.318 |

| 21. | Groenen H, Bontekoning N, Jalalzadeh H, Buis DR, Dreissen YEM, Goosen JHM, et al. Incisional wound irrigation for the prevention of surgical site infection: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Surg 2024 Jul 1; 159(7): 792–800. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2024.0775 |

| 22. | Carballo Cuello CM, Fernández-de Thomas RJ, De Jesus O, De Jesús Espinosa A, Pastrana EA. Prevention of surgical site infection in lumbar instrumented fusion using a sterile povidone-iodine solution. World Neurosurg 2021 Jul; 151: e700–6. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.04.094 |

| 23. | Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions [Internet]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook [cited 27 February 2025]. |

| 24. | The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews | The BMJ [Internet]. [cited 2025 Feb 27]. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 |

| 25. | Schünemann HJ, Cuello C, Akl EA, Mustafa RA, Meerpohl JJ, Thayer K, et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2019 Jul; 111: 105–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012 |

| 26. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019 Aug 28; 366: l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898 |

| 27. | Abdallah DY, Jadaan MM, McCabe JP. Body mass index and risk of surgical site infection following spine surgery: a meta-analysis. Eur Spine J Off Publ Eur Spine Soc Eur Spinal Deform Soc Eur Sect Cerv Spine Res Soc 2013 Dec; 22(12): 2800–9. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2890-6 |