ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Implementation of E-consent in infectious & isolated patients: a novel cost-conserving technique

Gerald Tse* and Yoong Chuan Tay

Division of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore

Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for innovative solutions to enhance infection prevention and control measures in healthcare settings, particularly for infectious and isolated patients.

Objective: To describe the implementation of a novel cost-conserving electronic procedural consent technique in infectious and isolated patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design: During the COVID-19 pandemic, we implemented an electronic consent technique using pre-existing hardware in the form of Toughbook tablets with styluses, and biohazard-grade ziplock bags. We trialled this method on patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 requiring surgery.

Results: This e-consent system was used in 83 patients undergoing surgery. Benefits included effective sanitization of the Toughbooks and the low cost. Challenges included suboptimal signature accuracy and the need for a back-up method when the Toughbook malfunctioned, or where e-signatures could not be obtained. The system was discontinued as the pandemic and isolation measures eased.

Discussion: The e-consent system provided a practical solution during the pandemic, reducing physical contact and supporting infection control. While effective, challenges related to technology and patient adaptability remained. The system demonstrated potential for broader applications, including in telemedicine and isolation care, but requires further evaluation in high-volume settings.

Conclusions: E-consent effectively minimized the risk of infection transmission and improved consent workflows. Beyond the pandemic, e-consent offers long-term benefits in infection prevention, consent management, and remote access, supporting safer, more flexible patient care across clinical settings. However, further studies are needed to evaluate its impact on reducing infection transmission and personal protective equipment (PPE) waste.

MeSH Keywords: informed consent; infection control; COVID-19; electronic health records; healthcare cost

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2025, 21: 23812 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v21.23812

Copyright: © 2025 Tse and Chuan Tay. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 23 October 2024; Accepted: 8 June 2025; Published: 21 August 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflicts of interest. The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

*Gerald Tse, Division of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Outram Road, Singapore, 169608, Singapore. Email: geraldtsejl@gmail.com

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for innovative solutions to enhance infection prevention and control (IPC) measures in healthcare settings, particularly for infectious and isolated patients (1). Traditional consent processes, typically reliant on pen-and-paper based methods, present numerous challenges exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. These challenges include the increased number of patients requiring contact precautions, surface contamination risks with paper as a vector for transmission (2), frequent handling of paper forms by healthcare staff, the difficult sanitizing of paper and pen (3), and logistical challenges including the increased use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and waste management such as the proper storage or disposal of paper forms (4).

The global pandemic also imposed significant restrictions on imports, and accessibility to and funding for new medical supplies, including technological solutions (5, 6). This situation highlighted the need for a sustainable and resource-efficient approach to healthcare innovation, particularly due to the uncertainty around when supply chains would return to normal.

Electronic consent (e-consent) offers a promising alternative, leveraging digital technologies to minimize the risk of infection transmission (7). In this paper, we describe the implementation of a novel cost-conserving method of e-consent, for infectious and isolated patients in a tertiary hospital. This approach capitalized on existing hardware and intranet networks to avoid the need for new purchases, ensuring a sustainable system under uncertain supply conditions. We also explored the benefits and challenges of implementing e-consent in the field of IPC, as well as its potential to transform consent practices in healthcare and its implications for broader adoption in clinical settings.

Methods

In March 2020, a satellite operating theatre (OT) complex (henceforth the COVID-OT) at the Singapore General Hospital (SGH) was converted into a separate surgical facility specifically for performing surgeries on patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19, in order to reduce the risk of cross-infection with other patients. The COVID-OTs were situated away from the major OT complex, with dedicated PPE stations, and allowed for strict airborne and contact precautions. The need for an alternative consent process and documentation arose.

The e-consent method was centered around the use of pre-existing Toughbook tablets, combined with simple, cost-effective solutions such as biohazard-grade ziplock bags and styluses for digital signatures. This averted the need for new purchases during the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach was developed and refined through discussions with the SGH Infection Prevention and Epidemiology (IPE) team and approved by the Hospital’s Medical Board. The e-consent method was initially piloted by the Anaesthesia Department. Consent for anaesthesia is typically obtained when the patient arrives at the COVID-OT, making this a critical point to minimize contact and streamline the consent process.

The SGH protocol was designed taking into account practicality and safety. The key elements included:

- 1) Toughbook tablets (Panasonic CF-MX4): Existing hospital-issued Toughbooks were adapted for the secure and portable collection of digital patient signatures on the anaesthesia consent forms. The Toughbooks are rugged 2-in-1 laptops that have a flip-over screen that can be rotated and laid flat, allowing them to be used as either tablets or laptops. These Toughbooks complied with our institution’s information technology and security guidelines and had intranet access, including to the hospital’s electronic health record (EHR) platform Citrix Sunrise Clinical Manager (SCM). They were typically issued to all doctors.

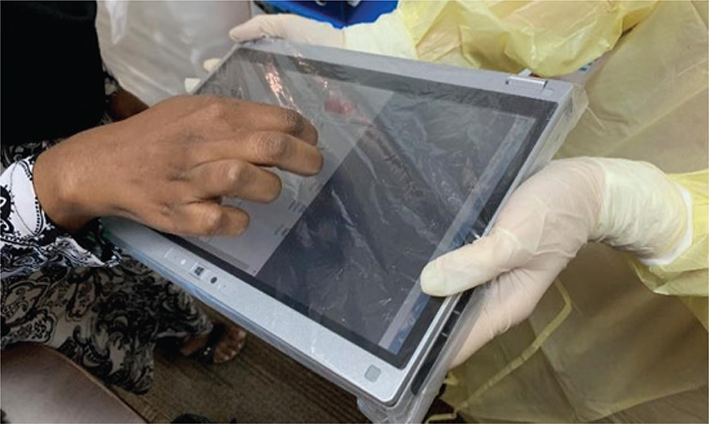

- 2) Cost-effective ziplock bags: To prevent contamination and allow safe reuse of the Toughbooks, they were placed into repurposed, single-use ziplock bags during patient interactions. Figure 1 shows a photograph of a patient signing on the ziplock-wrapped Toughbook. The ziplock bags (38 cm × 30.5 cm, 0.5 mm thick) were typically used for pathological specimens and withstood standard chemicals and specimens without leaks. The ziplock bags provided a barrier that could be cleaned easily between patient interactions.

- 3) Electronic PDF consent form: An electronic PDF copy of the consent forms was uploaded onto the Toughbooks. This format allowed digital signatures to be placed on the signature field of the PDF consent form.

- 4) Stylus for signatures: Patients used a stylus to sign on an electronic PDF copy of the consent form, through the ziplock barrier. This further reduced direct contact and minimized the risk of virus transmission.

- 5) Disinfection protocol: We implemented a strict cleaning protocol using alcohol-based disinfecting wipes (Schulke Mikrozid AF wipes) to disinfect the ziplock bags, styluses, and Toughbooks after each use. This method was superior to traditional paper consent forms, which could not be effectively sanitized between uses.

- 6) Wireless printing: While the hospital’s electronic system was not yet capable of integrating e-consents into Citrix SCM, a wireless connection to printers allowed for the printing of physical consent forms. This ensured that current hospital protocols, which required physical copies for checking and documentation during the surgical sign-in, could still be maintained.

- 7) Two-person technique: Two persons were involved in the consent taking process. One person in full PPE would approach the patient with the prepared Toughbooks, and secure the patient’s consent and digital signature. The second person would retrieve the Toughbooks from within the ziplock bag without contacting contaminated areas. This further prevented possible cross-contamination.

- 8) Reinforcement of the process: This e-consent process was promulgated to the Anaesthesia and Surgical Departments, as well as amongst the OT nursing staff. To facilitate adoption, detailed pictorial step-by-step guides were uploaded on the hospital’s intranet. This provided instructions on donning and doffing the ziplock onto the Toughbook, the disinfection protocol, and the steps to wirelessly print the signed PDF consent form.

Fig. 1. A patient signing on the ziplock-wrapped Toughbook with her fingers. This was subsequently changed to a stylus.

This method proved to be a cost-effective, safe, and practical solution during the pandemic, with potential for future integration into the hospital’s digital consent infrastructure.

Results

This e-consent process was used in 83 patients undergoing surgery from March 2020 to August 2020. Several challenges were encountered. Patients were not accustomed to signing on the plastic surface of the ziplock bags. The plastic ziplock barrier further complicated signature accuracy. The use of a stylus also introduced the risk of puncturing the ziplock bag with the stylus. To mitigate this, the hard-tipped styluses were replaced with soft round-tip styluses, allowing for safer interaction without compromising the integrity of the ziplock barrier.

A back-up consent method was also implemented as sometimes the Toughbook malfunctioned, or adequate e-signatures could not be obtained from patients. This method also did not allow fingerprints, which is the alternative for patients who were unable to physically provide signatures, to be captured. The back-up method involved using traditional paper consent forms, which were then placed in a plastic sleeve with a cut-out area where the patient could sign with a traditional pen. This minimized the contact between the patient and the paper consent form.

There were reports of Toughbook malfunctions, which led to the use of the back-up paper consent method. These issues occurred despite robust trials of the e-consent protocol, using the same hardware and wireless connection, prior to implementation. Challenges related to the implementation of e-consent included a drop in wireless signal at the COVID-OT, unfamiliarity with the new e-consent method, reluctance to move away from quicker paper-based consent forms, and frustration with the use of the stylus. A new replacement Toughbook was introduced to address the reported malfunctions. After its deployment, the entire process was trialled again. This second round of trials was successful, demonstrating that the replacement Toughbook functioned as intended. The successful trial suggested that the initial issues were likely due to factors such as intermittent wireless connectivity, user unfamiliarity with the e-consent method, and a preference for traditional paper-based consent methods, rather than a fundamental flaw in the e-consent system itself. To improve compliance and minimize confusion, the e-consent pictorial protocol was incorporated into the regular COVID-19 notification emails, in addition to being available on the hospital intranet.

Ultimately, the use of this e-consent system was discontinued as the pandemic situation normalized, reducing the need for strict isolation measures and leading to a return to traditional consent methods.

Discussion

The implementation of e-consent at SGH during the COVID-19 pandemic yielded mixed results. This method reduced the risk of contamination and minimized physical contact during consent processes, addressing key concerns in IPC. We also leveraged pre-existing hardware and intranet networks and used economical barrier methods. This method allowed a timely and sustainable implementation, as the disruption to supply chains during the pandemic had already produced a global financial strain. However, the adoption of e-consent was not without challenges. One challenge was the difficulty patients faced when signing on the Toughbook trackpad, particularly while interacting through the ziplock barrier. This led to the use of styluses, which improved usability but introduced a risk of puncturing the protective plastic. This issue highlighted the need for soft, round-tip styluses, which could maintain signature accuracy without compromising safety. This e-consent method also did not allow for patients to use fingerprints as an alternative to signatures. A possible solution could be to use photographic documentation of the patient, with direct integration into the consent form, although this also presents ethical and personal data protection implications.

Other institutions have also adopted e-consent systems; however, many encounter similar challenges, particularly in the absence of fully digital healthcare infrastructure (8). We used novel manual methods as an alternative, such as creating cut-outs in plastic covers to allow for paper-based consent, but this posed greater risks of contamination. The transition to fully paperless consent systems often requires significant infrastructure upgrades, involving both hardware and software modifications, as well as substantial capital investment. This highlights the need for time and resources to ensure compatibility with existing hospital systems.

Implications of E-consent for IPC

The results from SGH’s e-consent pilot system have notable implications for the field of IPC. E-consent minimizes physical contact and surface contamination (8). Hardware surfaces are also easier to sanitize compared to paper surfaces. The removal of paper forms also eliminates the presence of a fomite that is passed around among healthcare staff.

E-consent allows for the consent process to be conducted remotely via video calls or phone conversations, minimizing the need for in-person interactions between patients and healthcare staff. This is advantageous during pandemics, when reducing physical contact is crucial to limit virus transmission (7). Beyond pandemic situations, e-consent has broader applications such as in the intensive care units, or for patients requiring airborne, contact or protective isolation precautions. By facilitating remote consent discussions, e-consent reduces the need for healthcare staff to wear PPE during these interactions. Reducing PPE use and waste is important, particularly when it is a limited resource during pandemics and as healthcare shifts towards greater sustainability (4). However, further studies are needed to assess the true impact of e-consent on reducing infection transmission and PPE waste, particularly over prolonged periods and in high-volume clinical environments.

Electronic systems can provide better tracking of consent completion and ensure that all necessary information is documented accurately. This reduces the likelihood of incomplete forms necessitating retaking of consent, which can lead to operational delays and potential safety risks (9).

Implications of E-consent for the institution

The pilot testing of e-consent at SGH occurred during a period of infrastructure transition, as the hospital awaited a shift to the Epic electronic healthcare records platform (EPIC) electronic healthcare records platform. The temporary adoption of e-consent protocols allowed SGH to test the system while maintaining the current consent workflows, minimizing disruption to staff and avoiding the need for extensive retraining. This ensured that, if another pandemic arose, staff would be familiar with both paper and digital consent methods, which would avoid confusion and maintain efficiency.

Future of E-consent in healthcare

The future of e-consent holds great promise, particularly in the context of healthcare informatics. Its applications extend beyond surgical and procedural consent to research consents, and it could be used for intensive care and high dependency units or in telehealth clinics.

Key benefits include:

- Safety: Reducing the risk of infection transmission during consent processes.

- Accessibility & flexibility: Patients and research participants can review and sign consent forms remotely, improving convenience and participation.

- Improved comprehension: E-consent allows the incorporation of multimedia, enhancing patient understanding of procedures and research.

- Cost-effectiveness: Reduces reliance on paper, cutting down paper waste and associated costs.

- Efficiency: Decreases the need for face-to-face interactions and enables automated storage, which enhances the auditing and validation process.

Moreover, e-consent allows for the tracking and auditing of consent in real time and the potential for updating consent forms as needed. This flexibility will be especially valuable in telehealth settings where consent can be obtained remotely without physical presence.

Challenges of E-consent

Despite its advantages, several challenges must be addressed to ensure the successful implementation of e-consent. These include:

- Patient-related challenges: Limited digital literacy and access to required hardware.

- Healthcare provider challenges: Additional training requirements and resistance to change, along with assessing the mental capacity of patients remotely.

- Institutional challenges: Significant costs for hardware, risks of technical failure, data security concerns, patient privacy issues, and ensuring regulatory compliance, particularly with regard to digital signatures.

There are also limitations for certain patient populations, such as those with limb or hand impairments, who may find it difficult to provide consent digitally. While solutions such as facial recognition or photographic consent could be explored, they raise further legal and ethical considerations.

Conclusion

The implementation of e-consent at our institution demonstrated the potential for reducing contamination risks and improving consent workflows, particularly in pandemic settings. By minimizing physical contact with paper forms and reducing the handling of shared materials, this system effectively addressed key infection control concerns. Moreover, this pilot innovation proved that e-consent could be successfully integrated into the existing electronic health system. The lessons learned provide valuable insights for handling high-volume institutional needs during future health crises and our institution’s upcoming transition to a new EHR system.

Transitioning to fully electronic consent systems not only enhances infection prevention but also streamlines daily procedural workflows, supports efficient storage of consent records, and allows for seamless remote access. These benefits extend beyond pandemic settings, offering long-term improvements in infection control, particularly for patients requiring isolation or those requiring telemedicine services. As healthcare systems worldwide adopt greater digitization, e-consent is poised to play a pivotal role in ensuring safer, more efficient, and flexible patient care across diverse clinical settings, with the added benefit of supporting robust IPC strategies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our colleagues from the Department of Infection Control and Epidemiology, Anaesthesia and Surgical Department, and OT nursing colleagues who were involved in the successful execution of this e-consent protocol. We are deeply appreciative of their efforts in advancing patient care and infection prevention during the pandemic.

Ethical approval

The study did not require IRB approval due to the nature of the study.

References

| 1. | Chimonas S, Lipitz-Snyderman A, Matsoukas K, Kuperman G. Electronic consent in clinical care: an international scoping review. BMJ Health Care Inform 2023; 30(1): e100726. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2022-100726 |

| 2. | Mehraeen E, Salehi MA, Behnezhad F, Moghaddam HR, SeyedAlinaghi S. Transmission modes of COVID-19: a systematic review. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2021; 21(6): e170721187995. doi: 10.2174/1871526520666201116095934 |

| 3. | Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect 2020; 104(3): 246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.022 |

| 4. | Mahmoudnia A, Mehrdadi N, Golbabaei Kootenaei F, Rahmati Deiranloei M, Al-E-Ahmad E. Increased personal protective equipment consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: an emerging concern on the urban waste management and strategies to reduce the environmental impact. J Hazard Mater Adv 2022; 7: 100109. doi: 10.1016/j.hazadv.2022.100109 |

| 5. | Gereffi G. What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about global value chains? The case of medical supplies. J Int Bus Policy 2020; 3(3): 287–301. doi: 10.1057/s42214-020-00062-w |

| 6. | Bown CP. How COVID-19 medical supply shortages led to extraordinary trade and industrial policy. Asian Econ Policy Rev 2022; 17(1): 114–35. doi: 10.1111/aepr.12359 |

| 7. | Jaton E, Stang J, Biros M, Staugaitis A, Scherber J, Merkle F, et al. The use of electronic consent for COVID-19 clinical trials: lessons for emergency care research during a pandemic and beyond. Acad Emerg Med 2020; 27(11): 1183–6. doi: 10.1111/acem.14141 |

| 8. | Rothwell E, Brassil D, Barton-Baxter M, Brownley KA, Dickert NW, Ford DE, et al. Informed consent: old and new challenges in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Transl Sci 2021; 5(1): e105. doi: 10.1017/cts.2021.401 |

| 9. | Reeves JJ, Mekeel KL, Waterman RS, Rhodes LR, Clay BJ, Clary BM, et al. Association of electronic surgical consent forms with entry error rates. JAMA Surg 2020; 155(8): 777. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1014 |