ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Factors associated with healthcare providers’ observance of infection prevention and control measures in acute care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada

Nicole M. Robertson1, Brenda L. Coleman1,2, Curtis Cooper3, Joanne M. Langley4, Louis Valiquette5, Iris Gutmanis1, Robyn Harrison6, Kevin Katz7, Mark Loeb8, Shelly A. McNeil9, Matthew P. Muller10, Jeff Powis11, Samira Mubareka12, Jeya Nadarajah13, Marek Smieja14, Saranya Arnoldo15, Sarah A. Bennett1 and Allison McGeer1,2

1Sinai Health, Toronto, ON, Canada; 2University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; 3Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; 4Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Halifax, NS, Canada; 5Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada; 6Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada; 7North York General Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; 8Hamilton Health Sciences Centre, Hamilton, ON, Canada; 9Department of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS, Canada; 10Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; 11Michael Garron Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada; 12Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada; 13Oak Valley Health, Markham, ON, Canada; 14St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON, Canada; 15William Osler Health System, Brampton, ON, Canada

Abstract

Background: The spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) prompted renewed attention to infection prevention and control (IPC) programs in healthcare settings.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate associations between factors derived from a hospital safety climate scale for respiratory diseases and Canadian healthcare providers’ (HCPs) hand hygiene and eye protection practices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design: Cross-sectional analysis of the COVID-19 Cohort Study (2020–2023) of acute care HCPs providing direct patient care.

Results: 100% compliance with Canadian guidelines for the use of eye protection was reported by 73.7%, hand hygiene before entering rooms by 65.3%, and after exiting patient rooms by 81.8% of the 1,361 participants. The adjusted incidence rate ratio (aIRR) for hand hygiene after exiting a patient room was significantly higher for participants who rated organizational support for health and safety higher. The aIRR for the use of eye protection was significantly higher for people who rated their hospital as having fewer job hindrances related to completing their job while using protective equipment and reported higher ratings of their organization’s availability of protective supplies.

Discussion: Our data support the association between HCPs’ perception of hospital safety-related organizational factors and the use of eye protection and practice of hand hygiene. These findings also suggest that ease of access impacts the use of eye protection.

Conclusions: Although training and making equipment available are necessary, the perception of organizational factors, namely support for health and safety and absence of job hindrances, are important for improving the use of eye protection and hand hygiene.

MeSH keywords: infection control; health personnel; personal protective equipment; hand hygiene; eye protective devices; COVID-19; hospitals

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2025, 21: 23808 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v21.23808

Copyright: © 2025 Nicole M. Robertson et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 9 October 2024; Revised: 27 March 2025; Accepted: 8 June 2025; Published: 28 August 2025

To access the supplementary file, please visit the article landing page

This research was presented as a poster at the 34th European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Barcelona, Spain, April 27–30, 2024. Methods in this paper have been supplemented and altered based on preliminary findings.

Competing interests and funding: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [173212 & 181116]; the Weston Family Foundation [no number]; and Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation [6014200738]. Funders had no role in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, nor the decision to submit it for publication.

*Brenda L. Coleman, 600 University Avenue, Sinai Health, Toronto, ON M5G 1X5, Canada. Email: b.coleman@utoronto.ca

Coronaviruses, previously associated most often with the common cold in humans, have increased in their public health significance over the last two decades with the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) in 2003, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) in 2012, and SARS coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) in 2019 (1–3). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2, spread globally despite attempts to control transmission (4). With this arose renewed attention to infection prevention and control (IPC) programs aimed at reducing the spread of infections within healthcare settings.

Background

Updated Canadian IPC guidelines recommend that facilities aim for 100% hand hygiene adherence and the use of medical masks and eye protection in acute healthcare settings during periods of increased transmission of respiratory diseases spread via infectious respiratory particles, including SARS-CoV-2 (5). Hand hygiene and facial protection (i.e. the use of medical masks/N95 or equivalent respirators and eye protection such as goggles or a face shield) have been confirmed as important tools for reducing healthcare providers’ (HCPs’) occupational risk of SARS-CoV-2 (6, 7).

Reducing the spread of highly transmissible pathogens, such as SARS-CoV-2, requires a multi-faceted approach. Making personal protective equipment (PPE) and hand hygiene facilities readily available and having adequate training on their use is necessary, but not sufficient, to ensure consistent use (8). Other factors, such as a climate of safety within the workplace, also have an impactful role (8, 9). A safety climate refers to the perceptions held by employees about the value placed on safety in their work environment (10). Several factors comprise a workplace safety climate including organizational safety norms as well as policies and procedures that promote and communicate an organization’s commitment to safety (11). The hospital safety climate scale (HSCS) (11) is one of several different tools for use within hospital settings considered to have adequate psychometric properties (12).

This sub-study aimed to investigate the association between HCPs’ perceptions of organizational and environmental factors, as measured by a version of the HSCS (11, 13) adapted for respiratory diseases, and their level of use of eye protection and hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This study was conducted as part of the COVID-19 Cohort Study, a 42-month prospective cohort study conducted with HCPs recruited from 19 acute care, rehabilitation, and complex care hospitals across four Canadian provinces (Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, Nova Scotia). Recruitment occurred immediately following ethical approval at each site, with staggered enrolment from June 2020 to June 2023. Recruitment, consent, and completion of surveys were conducted electronically due to COVID-19 restrictions (14).

Participants were eligible for inclusion in these analyses if they were 18 to 75 years old at enrolment, worked > 20 h per week (a requirement of the parent study), and had patient facing roles with direct patient contact for ≥ 1 h per week. Participants were eligible irrespective of their COVID-19 vaccination status or history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Those indicating their gender as other than male or female were excluded due to the small sample size that precluded precise parameter estimates.

After consenting, participants were asked to complete an anonymous online baseline questionnaire to capture their exposure profile with questions pertaining to personal, household, and work characteristics, including hospital safety climate questions. All data used in the following analyses were collected in the baseline questionnaire. Only observations with complete data were used (50 observations were dropped due to incomplete information on either the exposure or the outcome).

The framework for these analyses was based on the review by Houghton et al., (8) who based their review on the Theoretical Model to Explain Self-Protection Behaviour at Work (9). They used organizational, environmental, and individual factors to assess HCPs’ adherence to guidelines during respiratory outbreaks. Organizational factors included the safety climate, communication of IPC guidelines, and availability of training while environmental factors included the physical environment and availability of PPE. To assess these factors in this study, HCPs were asked a series of questions adapted from the HSCS, a 20-question scale developed to measure hospitals’ commitment to bloodborne pathogen risk management (11). The items were asked at the end of the baseline questionnaire, following questions about the use of masks, goggles/face shields, and the performance of hand hygiene. Participants were asked to select the level of agreement that best reflected their opinion. Scores for items range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) points with higher scores indicating higher ratings. Our data collection tool generally followed that of an adaptation of the HSCS by Nichol et al. (13) for use with respiratory illnesses. See Supplementary Table 1 for differences in questions and wording adapted for use for respiratory illnesses. Of note, Nichol et al. categorized training as an environmental, rather than organizational, factor; our study has maintained this assignment (13).

HCPs’ self-reported use of eye protection and hand hygiene (before entering and after exiting patient rooms) were dichotomized as 100% completion (met Canadian guidelines (5)) versus < 100%. Self-reported use of medical masks was not part of these analyses since the use of medical masks in healthcare facilities was mandated by governing bodies and/or hospital policies during the data collection period (15). Potentially confounding variables, identified a priori, were age, gender, education, occupation, primary work unit (e.g. emergency department, out-patient clinic), years of experience, long-term or chronic medical condition, history of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination status, rate of hospitalization due to COVID-19 in the Canadian population, and wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (16). Cohort was assigned to participants based on their worksite/the participating hospital system.

Statistical analyses

Factor analysis

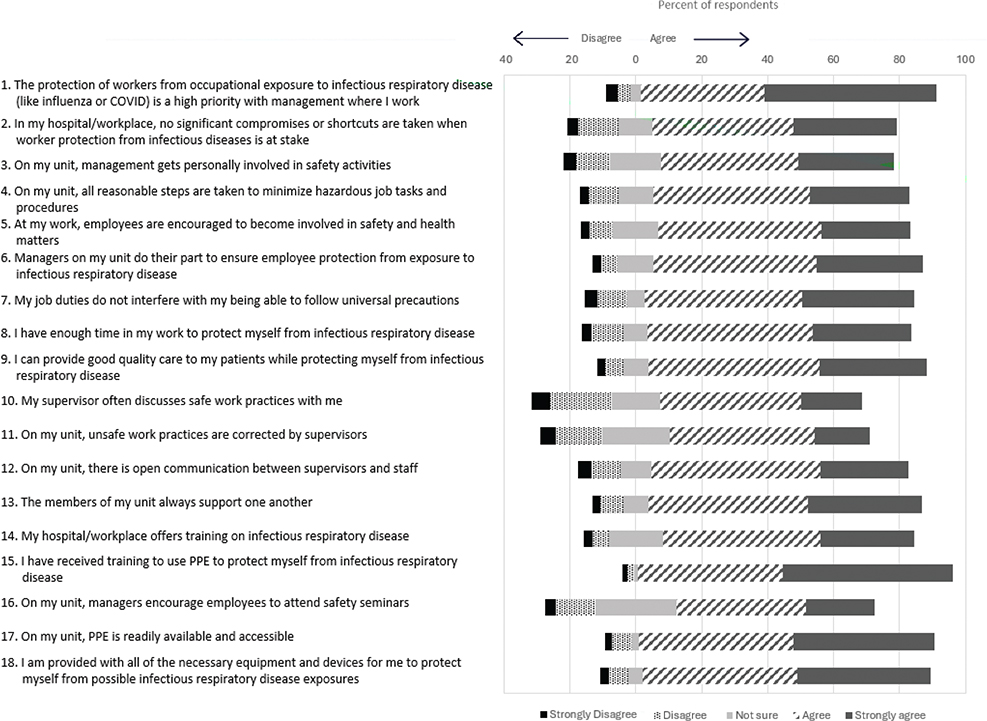

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to determine how to meaningfully categorize survey ‘items’/questions (N = 18 as listed in Fig. 1) into respective ‘factors’ (a smaller set of variables that measure one or more underlying constructs). Based on previous research, the factors were hypothesized to include six factors that underlie two constructs: organizational support (management support, absence of job hindrances, good communication/minimal conflict, feedback) and environmental support (availability of PPE/supplies, training) (8, 9, 11, 13, 17, 18).

Fig. 1. Distribution of responses to respiratory safety climate items as measured at enrolment to the COVID-19 Cohort Study; Canadian healthcare providers with direct patient contact (June 2020–June 2023). Numbers beside the items indicate the order items were asked in the questionnaire.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to assess sampling adequacy and suitability of factor analysis for these data (19, 20). We used Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin correlation of 0.60 as our cut-off and a significance level of P < 0.05 to evaluate Bartlett’s test of sphericity (21, 22). Cattell’s scree test was used to determine the number of factors to retain (23, 24). A correlation matrix was used to determine the relationship between variables. The matrix was inspected for correlation coefficients; values of < 0.30 indicated a weak relationship between variables (22). Variables with squared multiple correlation values close to 0 or close to 1 were removed due to the presence of multicollinearity or singularity (25).

Principal axis factoring was used to extract factors using a pre-specification of six factors. Factor loadings were analyzed using the varimax orthogonal rotation method with a factor loading cut-off of 0.40. Items that cross-loaded were reviewed to determine where inclusion was most appropriate, with each item included in only one factor. Rotated factors with only two items were considered reliable only if the variables were highly correlated with one another (i.e. r > 0.70) and had low correlation with other items (22, 25). This information was then used to inform the number of factors to retain and the assignation of items to factors for the final EFA-generated model.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to measure the performance of the proposed full model and the model designed from the EFA. Cut-offs used to indicate an acceptable model fit included a standardized root mean squared residual close to 0.08, a comparative fit index and Tucker–Lewis index close to 0.95, and root mean square error of approximation of close to 0.06 (26). These indices of fit were used to determine, which model was appropriate for the remainder of the analyses.

Multivariable methods

Using mean factor scores from the factor analysis, modified multivariable Poisson regression models (27), accounting for clustering within cohort, were used to assess how each factor was associated with HCPs’ reported use of eye protection and hand hygiene. All models were built separately using model building strategies following that of Vittinghoff et al. (28) to identify relevant confounding variables; a consistent composition of confounding variables were included in each of the final models. All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE 18.0 software (29) using two-sided tests with significance set at P < 0.05. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for flow chart of analytic steps.

Results

The mean age of the 1,361 eligible HCPs was 40.4 years, 1,163 (85.5%) identified themselves as female, and 703 (51.7%) as a nurse, nurse practitioner, or midwife. See Table 1 for complete demographic details.

| Characteristic | Participants N = 1,361 |

| Age in years, mean (95% CI) | 40.4 (39.8, 40.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 1,163 (85.5) |

| Male | 198 (14.5) |

| Education, highest achieved | |

| College diploma or less | 281 (20.6) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 658 (48.3) |

| Master’s degree | 189 (13.9) |

| MD or PhD | 233 (17.1) |

| Occupation | |

| Nurse/nurse practitioner/midwife | 703 (51.7) |

| Physician/physician assistant | 224 (16.5) |

| Other regulated health professional1 | 360 (26.5) |

| Other2 | 74 (5.4) |

| Work experience | |

| < 5 years | 328 (24.1) |

| 5 to 14 years | 520 (38.2) |

| ≥ 15 years | 513 (37.7) |

| Primary work unit Out-patient |

294 (21.6) |

| Adult medical in-patient | 280 (20.6) |

| Emergency department | 174 (12.8) |

| Adult intensive care | 172 (12.6) |

| Surgery | 133 (9.8) |

| In-hospital clinic | 85 (6.2) |

| Maternity | 74 (5.4) |

| Level 2 or 3 neonatal nursery | 47 (3.5) |

| Long-term care/alternate level of care | 34 (2.5) |

| Pediatric in-patient | 24 (1.8) |

| Laboratory, administration, research | 15 (1.1) |

| Other3 | 15 (1.1) |

| Mental health | 14 (1.0) |

| Chronic illness4 | 303 (22.3) |

| No | 1,058 (77.7) |

| SARS-CoV-2 prior to questionnaire | 93 (6.8) |

| No | 1,268 (93.2) |

| Vaccination status, with primary series5 | |

| Unvaccinated/incomplete | 614 (45.1) |

| Complete | 733 (53.9) |

| Missing vaccination data | 14 (1.0) |

| Province | |

| Ontario | 827 (60.8) |

| Alberta | 293 (21.5) |

| Quebec | 122 (9.0) |

| Nova Scotia | 119 (8.7) |

| Pandemic wave | |

| Wave 1 (Jun 15, 2020 – Aug 29, 2020) | 225 (16.5) |

| Wave 2 (Aug 30, 2020 – Mar 6, 2021) | 279 (20.5) |

| Wave 3 (Mar 7, 2021 – Jul 31, 2021) | 460 (33.8) |

| Wave 4 (Aug 1, 2021 – Nov 27, 2021) | 312 (22.9) |

| Waves 5/6/7 (Nov 28, 2021 – Jun 31, 2023) | 85 (6.3) |

| Hospitalization rate for COVID-19, per 100,000 Canadians | |

| Mean (95% CI) | 42.8 |

| Range (min, max) | 4.9, 202.3 |

| 1Respiratory therapist, laboratory technician, physical therapist, occupational therapist, imaging technician/technologist, pharmacist, pharmacy technician, psychologist, social worker. 2Food service, ward clerk, administration, healthcare aids, housekeeper, porter, research, other clinical support. 3Participants not tied to any specific unit (e.g. porter), listed multiple units, or did not specify a work unit. 4Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other chronic lung condition, diabetes, heart disease, cancer treated in the past 5 years, liver or kidney disease, HIV/AIDS or other immune suppressing disease/condition, chronic neurological disorder, or other long-term chronic conditions. 5Two doses of a two-dose vaccine or one dose of a single dose vaccine with a 10-day lag incorporated for time to mount an immune response. |

|

Distributions of responses to the respiratory safety climate items are provided in Fig. 1. Overall, there was high agreement with all questions, with 13 of 18 in which > 75% of participants either agreed or strongly agreed. ‘I have received training to use PPE to protect myself from infectious respiratory disease’ had the strongest level of agreement at 95.5%. The item with the highest level of disagreement was ‘My supervisor often discusses safe work practices with me’, with 24.2% of participants disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. The question with the most uncertainty among participants was ‘On my unit, managers encourage employees to attend safety seminars’, with 12.3% of participants selecting ‘not sure’ in response.

Performance of respiratory safety climate questions

Indices of fit for the full 6-factor/18-item model and the EFA-generated 4-factor/16-item model were similar (see Table 2). Both models explained roughly 57% of the variance in responses. Given this and the notable difference in the loadings of items between the original and EFA models, the EFA-generated model was used for the remainder of the analyses. The results of the EFA for all 18 items are available in Supplementary Table 2.

Using the rotated factor loading scores, the scree test, and reviewing correlation scores between items for factors where only two items loaded, four factors were retained and grouped under the two constructs: organizational, consisting (organizational support for health and safety, absence of job hindrances) and environmental (availability of PPE/supplies, training).

In the 4-factor/16-item model (rotated factors loadings presented in Table 3), two items of the original HSCS’s management support factor were dropped (#1 and 2 in Fig. 1). And, as shown in Supplementary Table 2, these items loaded onto a new factor when a 6-factor model was specified. Two items (#10 and 11) that loaded onto the feedback/training factor of the original scale and two items (#12 and 13) that originally loaded onto the minimal conflict/good communication factor now loaded to the management support factor. Two items related to training (#14 and 15) that were initially grouped under the feedback/training factor of the HSCS loaded onto their own factor. Note that the two items in the training factor had a low correlation between them (r = 0.52), so should be interpreted with caution. Other items loaded to the same factors identified in the HSCS.

| Items1 | Rotated factor loadings | |||

| Organizational support | Absence of job hindrances | Availability of PPE / supplies | Training | |

| 3) On my unit, management gets personally involved in safety activities | 0.71 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.07 |

| 4) On my unit, all reasonable steps are taken to minimize hazardous job tasks and procedures | 0.61 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.03 |

| 5) At my work, employees are encouraged to become involved in safety and health matters | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| 6) Managers on my unit do their part to ensure employee protection from exposure to infectious respiratory disease | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.36 | 0.07 |

| 7) My job duties do not interfere with my being able to follow universal precautions | 0.24 | 0.66 | 0.23 | 0.09 |

| 8) I have enough time in my work to protect myself from infectious respiratory disease | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.24 | 0.07 |

| 9) I can provide good quality care to my patients while protecting myself from infectious respiratory disease | 0.20 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.13 |

| 10) My supervisor often discusses safe work practices with me | 0.70 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.21 |

| 11) On my unit, unsafe work practices are corrected by supervisors | 0.67 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| 12) On my unit, there is open communication between supervisors and staff | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| 13) The members of my unit always support one another | 0.382 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.19 |

| 14) My hospital/workplace offers training on infectious respiratory disease | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.47 |

| 15) I have received training to use PPE to protect myself from infectious respiratory disease | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.38 | 0.41 |

| 16) On my unit, managers encourage employees to attend safety seminars | 0.54 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.39 |

| 17) On my unit, PPE is readily available and accessible | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.76 | 0.11 |

| 18) I am provided with all of the necessary equipment and devices for me to protect myself from possible infectious respiratory disease exposures | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.76 | 0.09 |

| Percent of variance (all items) | 25% | 13% | 14% | 5% |

| Bold loading factor correlation meets 0.40 cut-off; greyed cells indicate the factor with which each item is associated. 1Items were asked as written. No further details, nor examples, were provided. 2Rotated factor loading score for this item was ≥ 0.40 in the full 6-factor/18-item model and was therefore grouped into organizational support for health and safety. |

||||

Association of the organizational and environmental factors with observance of IPC guidelines

Of the 1,361 participants, 889 (65.3%), 1,113 (81.8%), and 1,003 (73.7%) reported following Canadian guidelines (5) 100% of the time for hand hygiene prior to entering and after exiting a patient room, and wearing eye protection when indicated, respectively. Of note, 95.1% of participants reported using masks 100% of the times they were indicated, precluding the inclusion of this measure in further analyses due to small cell sizes. After adjusting the EFA-generated model for potential confounders, participants who reported 100% use of eye protection and completed hand hygiene for 100% of opportunities rated their organization’s support of health and safety issues and the absence of job hindrances higher than those who reported use for < 100% of opportunities. Note that while a positive association was found for all models investigating organizational factors, four of the six did not achieve statistical significance. As shown in Table 4, participants who reported the use of eye protection 100% of the time rated the availability of PPE/supplies higher than those who used eye protection less often (adjusted incident rate ratio [aIRR] 1.06; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02, 1.11). Training specific to infectious respiratory disease was not significantly associated with increased observance of any of the self-reported protective behaviours.

| Eye protection (100% vs. less) aIRR1 (95% CI) |

Hand hygiene before entering patient room (100% vs. less) aIRR1 (95% CI) |

Hand hygiene upon exiting patient room (100% vs. less) aIRR1 (95% CI) |

|

| Organizational factors Organizational support Absence of job hindrances |

1.05 (0.99, 1.11) 1.06 (1.01, 1.10)‡ |

1.05 (1.00, 1.11) 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) |

1.04 (1.00, 1.08)* 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) |

| Environmental factors Availability of PPE/supplies Training |

1.06 (1.02, 1.11)‡ 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) |

0.99 (0.95, 1.03) 1.01 (0.96, 1.08) |

1.01 (0.99, 1.03) 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) |

| *P < 0.05; ‡P < 0.01. 1Adjusted for age, gender, occupation, primary work unit, hospitalization rate and pandemic wave at time of questionnaire submission using modified Poisson regression with variance estimates adjusted for clustering within cohort. |

|||

Discussion

Our data support the association between Canadian HCPs’ perception of hospital safety-related organizational factors (i.e. support for health and safety and absence of hindrances to practice protective behaviors) and the use of eye protection and practice of hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic. The availability of PPE/supplies was associated with the use of eye protection but was not found to be associated with hand hygiene practices in this sample. Our findings support the utility of the HCSC during stressful working conditions such as a pandemic. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of HCPs’ perception about the attitudes and behaviors of their peers, supervisors, managers, and directors when making individual decisions about self-protective practices (9, 13, 17).

There are a number of studies that report a positive association between the use of protective measures in hospitals and the culture of organizational safety. Nichol et al. reported that Canadian nurses who perceived the presence of organizational support for safety were twice as likely to use facial protection (i.e. medical masks, N95 respirators and/or eye protection as indicated, with patients suspected or confirmed as having an infectious respiratory illness) as those who did not in both a 2006 cross-sectional pilot study and a larger cross-sectional follow-up study (13, 30). Jiang et al. reported that Canadian HCPs working during the four influenza seasons following the influenza A(H1N1pdm) pandemic who rated management support and absence of job hindrances higher on an adapted version of the HSCS were more likely to follow Canadian guidelines for droplet and contact precautions (31) (specifically the use of a medical mask or N95 respirator, gloves, eye protection, and hand hygiene) than those who rated them lower (17). Similarly, McCauley et al. reported that the overall culture of the ward (i.e. positive leadership by management, managerial and professional relationships, and effective communication) was positively associated with adherence to IPC protocols in their systematic review (32). A review by Brooks et al. concluded that observing peers and superiors completing hand hygiene was associated with others also doing so (33). Of interest, authors of a study of nurses working in COVID-19 designated hospitals in China reported that better perceptions of hospital safety climate were associated with lower levels of psychological distress as measured by the General Health Questionnaire-12 (34).

In our study, the use of eye protection and completion of hand hygiene were positively associated with the perceived absence of job hindrances for doing so. Job hindrances, such as perceived inconvenience, its impact on their ability to do their job, and a negative impact on patient care have been associated with lower use of PPE and hand hygiene (33). Other hindrances include unreasonably heavy workloads and increased care responsibilities, which were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (32, 35–38). Nichol et al. however, did not find a relationship between perceived absence of job hindrances and the use of facial protection by Canadian nurses during an interpandemic period (30). This discrepancy suggests that despite heavier workloads experienced by Canadian HCPs during the COVID-19 pandemic (39), the need to protect oneself and one’s patients were a top priority.

The only outcome associated with the availability of PPE/supplies in our study was the use of eye protection. The lack of availability of appropriate PPE has been reported to be associated with not performing personal protective behaviors in other studies (33, 38). Of note, our study commenced when PPE shortages were easing (40); 90% of participants agreed that PPE were readily available and accessible on their unit. The lack of a relationship between the availability of supplies and hand hygiene in this study was not unexpected given the emphasis on infection prevention, consistent availability of hand hygiene products, and the strategic placement of hand hygiene facilities within Canadian healthcare institutions (41). These findings suggest that ease of access impacts a less-often used protective behavior such as the use of eye protection while having little or no impact on hand hygiene, a routine practice recommended for all patient interactions.

In this study, training items on the survey were not associated with improved observance of any of the measured IPC practices. Literature regarding the effect of training varies widely across settings. Brooks et al. found little evidence that additional training and education during infectious disease outbreaks significantly improved compliance; they suggest that training should not be viewed as a panacea (33). There is an overall consensus, however, that a lack of training is a strong predictor of non-adherence (9). These authors therefore suggest that a threshold of adequate training needs to be met and maintained. Once this threshold has been achieved and sustained, as is common across Canadian hospitals, additional efforts and resources should be directed toward organizational factors to achieve increased impact.

Observed differences in factor loadings in this study compared to that of the original HSCS by Gershon et al. (11) suggests a difference in the workplace landscape, possibly related to the COVID-19 pandemic and, perhaps, due to assessing a respiratory disease rather than a bloodborne one. Several studies have identified themes of solidarity and collective resilience where frontline workers reported a perceived amplification of teamwork to manage increased risks and workload associated with the pandemic (42, 43). This collective experience, whereby an increased level of shared responsibility and reciprocated trust among all job level classifications was imperative, may have reduced the dissimilarity among factors that was reported in the original HSCS.

Although observational studies are a powerful research tool, there are risks of bias that may impact the reliability of the results. Although we used anonymized surveys, it is possible that social desirability bias occurred when reporting rates of preventive practices. Participation in this study was voluntary, therefore the sample may not be representative of the entire healthcare workforce due to a self-selection bias. Also, because data were collected across four regions (provinces) and over a 3-year period, uncontrolled confounding may have impacted the estimates of the associations between organizational and environmental factors and selected IPC practices. However, models were adjusted for pandemic wave, among other factors, to help reduce the impacts of confounding; analysis stratified by wave did not elicit differences in the study relationships, perhaps due to the small sample sizes. Models were also clustered by cohort to account for correlations between observations within the same hospital system. Also, the presence of mask mandates and policies during the pandemic precluded authors from investigating the relationship between organizational and environmental factors and behaviors related to the use of medical masks in this cohort.

Conclusion

The results of this study support the current body of literature indicating that HCPs’ perceptions of organizational support for safety is necessary above and beyond training and supplying PPE/equipment to maximize the use of protective practices. Given that < 100% of participants with direct patient contact reported using eye protection and practicing hand hygiene at 100% of opportunities, even during a pandemic, suggests that it may be helpful for institutions to review their safety climate and senior leadership’s understanding of such, to protect their employees and patients from infectious respiratory diseases.

Acknowledgments

The investigators thank their staff, who worked tirelessly throughout the study and the participants, who gave freely of their time even while experiencing the stress of working during the pandemic.

Authorship and manuscript preparation

The authors confirm contribution to the article as follows: conceptualization: NR, BLC; data curation: BLC, NR; formal analysis: NR; funding acquisition: BLC, AM, CC, KK, ML, SM, MM, JP, RH, JML, SM, JN, LV, MS; methods: NR, BLC; project administration: BLC; resources: BLC, AM; supervision: BLC; validation: BLC; original draft: NR, BLC; review & editing: BLC, NR, CC, JML, KK, ML, SM, MM, JP, RH, SM, JN, LV, AM, MS, IG.

References

| 1. | Bennett J, Dolin R, Blaser M. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc.; 2015. |

| 2. | Song Z, Xu Y, Bao L, Zhang L, Yu P, Qu Y, et al. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses 2019; 11(1): 59. doi: 10.3390/v11010059 |

| 3. | Yin Y, Wunderink RG. MERS, SARS and other coronaviruses as causes of pneumonia. Respirology 2018; 23(2): 130–7. doi: 10.1111/resp.13196 |

| 4. | World Health Organization. Listings of WHO’s response to COVID-19 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline [cited 2024 April 15]. |

| 5. | Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection prevention and control for COVID-19: interim guidance for acute healthcare settings 2021. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/health-professionals/infection-prevention-control-covid-19-second-interim-guidance.html [cited 2023 October 12]. |

| 6. | Hajmohammadi M, Saki Malehi A, Maraghi E. Effectiveness of using face masks and personal protective equipment to reducing the spread of COVID‑19: a systematic review and meta‑analysis of case–control studies. Adv Biomed Res 2023; 12(1): 36. doi: 10.4103/abr.abr_337_21 |

| 7. | Van Belle TA, King EC, Roy M, Michener M, Hung V, Zagrodney KAP, et al. Factors influencing nursing professionals’ adherence to facial protective equipment usage: a comprehensive review. Am J Infect Control 2024; 52(8): 964–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2024.04.006 |

| 8. | Houghton C, Meskell P, Delaney H, Smalle M, Glenton C, Booth A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 4(4): CD013582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013582 |

| 9. | Moore D, Gamage B, Bryce E, Copes R, Yassi A, Group BCIRPS. Protecting health care workers from SARS and other respiratory pathogens: organizational and individual factors that affect adherence to infection control guidelines. Am J Infect Control 2005; 33(2): 88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.11.003 |

| 10. | Zohar D. Safety climate in industrial organizations: theoretical and applied implications. J Appl Psychol 1980; 65(1): 96–102. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.65.1.96 |

| 11. | Gershon RR, Karkashian CD, Grosch JW, Murphy LR, Escamilla-Cejudo A, Flanagan PA, et al. Hospital safety climate and its relationship with safe work practices and workplace exposure incidents. Am J Infect Control 2000; 28(3): 211–21. doi: 10.1067/mic.2000.105288 |

| 12. | Jackson J, Sarac C, Flin R. Hospital safety climate surveys: measurement issues. Curr Opin Crit Care 2010; 16(6): 632–8. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32833f0ee6 |

| 13. | Nichol K, Bigelow P, O’Brien-Pallas L, McGeer A, Manno M, Holness DL. The individual, environmental, and organizational factors that influence nurses’ use of facial protection to prevent occupational transmission of communicable respiratory illness in acute care hospitals. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36(7): 481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.12.004 |

| 14. | Coleman BL, Gutmanis I, Bondy SJ, Harrison R, Langley J, Fischer K, et al. Canadian health care providers’ and education workers’ hesitance to receive original and bivalent COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine 2024; 42(24): 126271. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2024.126271 |

| 15. | Government of Ontario. Masking requirements continue in select indoor settings [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1002098/masking-requirements-continue-in-select-indoor-settings [cited 2025 March 27]. |

| 16. | Government of Canada. COVID-19 epidemiology update: current situation 2024. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/current-situation.html [cited 2024 March 05]. |

| 17. | Jiang L, Muller M, McGeer A, Simor A, Holness DL, Coleman KKL, et al. Assessing a safety climate tool adapted to address respiratory illnesses in Canadian hospitals. Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol 2024; 4(1): e157. doi: 10.1017/ash.2024.426 |

| 18. | Turnberg W, Daniell W. Evaluation of a healthcare safety climate measurement tool. J Safety Res 2008; 39(6): 563–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2008.09.004 |

| 19. | Bartlett MS. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol 1950; 3(2): 77–85. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x |

| 20. | Kaiser HF. A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika 1970; 35(4): 401–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02291817 |

| 21. | Netemeyer R, Bearden W, Sharma S. Scaling procedures. Thousand Oaks, CA; 2003. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/scaling-procedures [cited 2024 October 27]. |

| 22. | Tabachnick BG, Fiddell L.S. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2007. |

| 23. | Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behav Res 1966; 1(2): 245–76. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10 |

| 24. | Taherdoost H, Sahibuddin S, Jalaliyoon N. Exploratory factor analysis; concepts and theory. Adv Appl Pure Math 2022; 27: 375–82. |

| 25. | Yong A, Pearce S. A beginner’s guide to factor analysis: focusing on exploratory factor analysis. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2013; 9: 79–94. doi: 10.20982/tqmp.09.2.p079 |

| 26. | Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999; 6(1): 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 |

| 27. | Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159(7): 702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090 |

| 28. | Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2012. |

| 29. | StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: release 18. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2023. |

| 30. | Nichol K, McGeer A, Bigelow P, O’Brien-Pallas L, Scott J, Holness DL. Behind the mask: determinants of nurse’s adherence to facial protective equipment. Am J Infect Control 2013; 41(1): 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.12.018 |

| 31. | Public Health Agency of Canada. Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in healthcare settings [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2016. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publications/diseases-conditions/routine-practices-precautions-healthcare-associated-infections/routine-practices-precautions-healthcare-associated-infections-2016-FINAL-eng.pdf [cited 2025 March 26]. |

| 32. | McCauley L, Kirwan M, Matthews A. The factors contributing to missed care and non-compliance in infection prevention and control practices of nurses: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv 2021; 3: 100039. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100039 |

| 33. | Brooks SK, Greenberg N, Wessely S, Rubin GJ. Factors affecting healthcare workers’ compliance with social and behavioural infection control measures during emerging infectious disease outbreaks: rapid evidence review. BMJ Open 2021; 11(8): e049857. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049857 |

| 34. | Xie C, Zhang J, Ping J, Li X, Lv Y, Liao L. Prevalence and influencing factors of psychological distress among nurses in sichuan, china during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry 2022; 13: 854264. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.854264 |

| 35. | Efstathiou G, Papastavrou E, Raftopoulos V, Merkouris A. Factors influencing nurses’ compliance with Standard Precautions in order to avoid occupational exposure to microorganisms: a focus group study. BMC Nurs 2011; 10: 1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-1 |

| 36. | Henderson J, Willis E, Roderick A, Bail K, Brideson G. Why do nurses miss infection control activities? A qualitative study. Collegian 2020; 27(1): 11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2019.05.004 |

| 37. | Lee C-Y, Lee M-H, Lee S-H, Park Y-H. Nurses’ views on infection control in long-term care facilities in South Korea: a focus group study. Korean J Adult Nurs 2018; 30(6): 634–42. doi: 10.7475/kjan.2018.30.6.634 |

| 38. | Mutsonziwa GA, Mojab M, Katuwal M, Glew P. Influences of healthcare workers’ behaviours towards infection prevention and control practices in the clinical setting: a systematic review. Nurs Open 2024; 11(3): e2132. doi: 10.1002/nop2.2132 |

| 39. | Blackwell AJ. Quality of employment and labour market dynamics of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Statistics Canada; 2023. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2023001/article/00007-eng.pdf?st=XVNHLk9B [cited 2024 June 11]. |

| 40. | Government of Canada. Supplying Canada’s response to COVID-19 2022. Available from: https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/comm/aic-scr/provisions-supplies-eng.html [cited 2024 May 02]. |

| 41. | Canadian Standards Association. Health and safety by design: improving the future of healthcare facility design & construction with CSA Z8000-18 2018. Available from: https://www.csagroup.org/article/health-and-safety-by-design/ [cited 2024 June 11]. |

| 42. | Kinsella EL, Muldoon OT, Lemon S, Stonebridge N, Hughes S, Sumner RC. In it together?: exploring solidarity with frontline workers in the United Kingdom and Ireland during COVID-19. Br J Soc Psychol 2023; 62(1): 241–63. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12579 |

| 43. | Lavoie B, Bourque CJ, Côté A-J, Rajagopal M, Clerc P, Bourdeau V, et al. The responsibility to care: lessons learned from emergency department workers’ perspectives during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. CJEM 2022; 24(5): 482–92. doi: 10.1007/s43678-022-00306-z |