ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Nurses’ knowledge and practices regarding healthcare associated infections control measures in King Saalman bin Abdul-Aziz Medical City at Madinah City, Saudi Arabia

Amal Abdulrhaman Alrefaee1, Atef Mohmmad Shibl2, Qais Saif Eldaula Dirar3

1MBS Infection Control, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, KSA; 2Professor of Microbiology & Infection Control, Alfaisal University, KSA; 3Senior Lecture of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Public Health, College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, KSA

Abstract

Background: Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs), also known as nosocomial infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Also, the nurses play a vital role to prevent and control the spread of HAIs.

Aim: This study aimed to assess the knowledge and practices of nurses regarding HAIs control measures in King Salman bin Abdul-Aziz Medical City (KSAMC) at Madinah City.

Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study, the total population of registered nurses is 1955 in KSAMC, although the target sample size is 322. Self-report questionnaires that consisted of 45 items were distributed by Google Forms among registered nurses working at KSAMC. The data collected was analyzed by Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS).

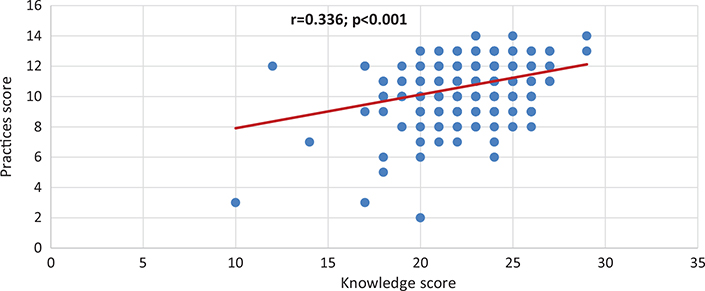

Results: The study found that most participants were female (79.5%), married (60.2%), had bachelor’s degrees (62.1%), and had work experience between 1 and 5 years (28%). Most nurses worked in maternity and children’s hospitals (51.2%), while emergency units (18%) were the most specialty departments. In addition, (58.4%) of nurses had a fair understanding of HAIs control measures. Among the nurses, 9 out of 10 (94.1%) had good knowledge of HH. In addition, the nurse’s practices regarding HAIs control measures (63.7%) were fair. There was a positive significant correlation observed between the knowledge and practices scores (r = 0.336).

Conclusion and recommendations: This study’s findings revealed that nurse’s knowledge and practices of HAIs infection control measures had fair knowledge and fair practices. A nurse needs constant reminders of infection control measures by attending regular and continuous health education and seminars related to preventing and controlling HAIs.

Keywords: knowledge; practices; nosocomial infections; healthcare associated infections; nurses

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2025, 21: 23716 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v21.23716

Copyright: © 2025 Amal Abdulrhaman Alrefaee et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 27 July 2023; Accepted: 4 June 2025; Published: 5 September 2025

Competing interests and funding: The authors have no conflict of interest regarding this work, and the study is not funded by any grant or organization.

*Amal Abdulrhaman Alrefaee, Infection Control, College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, KSA

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) also referred to as ‘nosocomial’ or ‘hospital’ infections represent the most frequent and serious complications of healthcare (1). HAIs are infections that patients acquire while receiving treatment for other medical or surgical conditions in a healthcare setting. They are not present or incubating at admission but are developed during the course of care. Some of the most prevalent HAIs include catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI), central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI), peripheral line-associated bloodstream infections (PLABSI), surgical site infections (SSI), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). Such infections typically happen as a result of the insertion of invasive medical devices such as urinary catheters, central venous catheters, peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC), and mechanical ventilators. In addition, HAIs can also result following surgery from the surgical procedures. A further essential aspect is that healthcare workers themselves are susceptible to contracting HAIs in the process of treating infected patients, particularly if infection control protocols are not correctly adhered to. Therefore, effective adherence to both Standard Precautions and Transmission-Based Precautions is essential in preventing the spread of HAIs in health care facilities. HAIs are infections acquired during healthcare that were not present at the time of admission (2).

HAIs are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients and are an indicator of poor quality in healthcare facilities (3). Furthermore, its impacton families, communities, and countries at large includes lengthened hospital stays, higher healthcare costs, and increased economic burdens (4). The WHO estimates that most developed countries have a prevalence of HAIs of 7% while developing countries have a prevalence of 10% (5).

In Saudi Arabia, according to the Ministry of Health (MOH) and General Directorate of Infection Prevention (GDIPC), there were more HAIs outbreaks in 2021 than the previous year. Compared to 2015, there were (122) reports of HAI outbreaks in 2021. In 2021, there was a 21% increase from 2020 to 2021(MOH, 2021). Based on 496 HAIs outbreak cases, vascular access (86%), Foley catheters (76%), and mechanical ventilation (75%), were the most commonly associated devices (MOH, 2021). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s health economist has assessed the yearly hospital expenses of HAIs in the United States to be between US $28 billion and US $45 billion (6). In addition, nurses play a vital role in communicating HAIs, and they consistently follow disease control measures to prevent and control the spread of HAIs. In addition, they should be aware of how to prevent the spread of HAIs and should know that they can harm patients, other staff, and their guests (7).

Background

The HAIs otherwise call nosocomial infection (NI) is Infection that develops within a hospital or other healthcare facility in a patient who is not already infected or incubating the infection (8). The HAIs are commonly transmitted in hospital settings due to non-sterilized instruments, untrained staff, and a lack of awareness about infection prevention practices. In addition, immunocompromised patients who visit the hospital are more likely to contract HAIs, as there is direct contact between healthcare workers and patients (9).

In addition, according to reports, the incidence of NIs in the intensive care unit is around 2 to 5 times greater than in the general inpatient hospital population (10). The result of an HAIs can be a poor quality of life or even a reduced life expectancy, as well as substantial long-term costs (11).

The knowledge and awareness of infection control practices of nurses has been examined by Salem (10) and Hammoud et al. (12). For example, in Saudi Arabia, Salem carried out the cross-sectional study to examine the knowledge and practice of nurses in relation to infection control measures (10). The study sample involved a total of 60 nurses working in medical and surgical units. Most nurses in the study had good knowledge of infection control measures. Regarding hand washing, Annals (78.3%) nurses had fair knowledge, while the rest of nurses had good knowledge about hand washing afterward. Glove, disinfection, and discarding knowledge were good (71.7, 63.3, and 93.3%, respectively), (60%) of nurses had good knowledge. As a result of this study, nurses’ managers need to supervise staff nurses’ compliance with hospital policies and infection prevention standards and techniques.

In addition, Alrubaiee et al. conducted, conducted a cross-sectional study was conducted among 100 nurses working in private hospitals in Yemen in order to evaluate their knowledge and practices regarding NI control measures (13). The findings revealed that only 4% of the nurses had a good level of understanding of NI prevention, compared to most nurses (87%) who had a reasonable level of knowledge. As a result, it’s crucial to practice infection prevention and control (IPC) in medical and hospital settings to avoid the spread of NIs (7). Numerous studies have emphasized the Practices of Nurses in IPC.

According to (10) conducted a Convenient sample for 60 nurses cross-sectional research in the Saudi Arabia. The study intended to evaluate the knowledge and practice of nurses in relation to infection control measures. The study’s results showed a lack of practice in hand washing and using gloves, which are essential for preventing infection transmission. Generally, 51.7% of nurses had poor practice about infection control measures (10).

According to the Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices (KAP) study conducted in Zambia (14), 48.8% of cases involved poor IPC practices. It is necessary to conduct further research to better understand the barriers to infection control (14). A study performed in Pakistan to evaluate the knowledge and practices of nurses regarding the spread of NI in government hospitals of Lahore on 240 nurses by random sampling. This study revealed that the practices used to prevent NI were ineffective, because 81 (33.8%) people were neutral, and 72 (30.0%) people disagreed with the recommendation to use alcohol-based solution or other antiseptics before and after each patient contact (15).

It is essential to distinguish conceptually between the two general categories of IPC measures used in healthcare: Standard Precautions and Transmission-Based Precautions. Standard Precautions form the foundation of infection control and include 11 fundamental practices that must be followed by all healthcare workers when providing care to any patient, regardless of their infection status are as follows: hand hygiene, personal protective equipment (PPE) use, respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette, safe injection practices, safe handling and cleaning of patient-care equipment, environmental cleaning, safe handling of laundry and waste, safe patient transport, prevention of needle-stick injuries, and proper management of biological fluid exposure. Their purpose is to decrease the risk of transmission of infectious agents from known and unknown sources of infection.

In comparison, Transmission-Based Precautions are additional infection control precautions that are implemented when a patient is either known or suspected to be infected with specific pathogens that require more than standard precautions alone to prevent transmission. They are categorized based on the transmission route: contact, droplet, and airborne. Transmission-Based Precautions are added to Standard Precautions and are both agent and clinical-situation specific. For example, patients with or suspected of having tuberculosis would require airborne precautions along with standard practices.

With these definitions in mind, the clarification is in order that the assessment in this study measured the knowledge and adherence of nurses primarily on Standard Precautions. These include key features such as hand hygiene, PPE use, and appropriate cleaning of equipment that are similarly relevant to everyday clinical practice anywhere. This study found that the majority of participants had good overall knowledge regarding these precautions, with high awareness in certain areas such as hand hygiene. These findings are aligned with both regional and international literature, observing variations that can be accounted for by exposure to training, education level, and institutional policy differences.

Nurses’ actual compliance with these practices was also assessed by the study, which established that most participants had a fair level of practice in infection prevention. While study design did not specifically evaluate compliance with Transmission-Based Precautions, some elements related to these precautions may have been indirectly evaluated by questionnaire. The study also recorded a positive correlation between knowledge and practice scores, which means that the better the knowledge of infection control guidelines, the better the practical application. The findings reinforce the need for continued education and training sessions on both Standard and Transmission-Based Precautions to boost infection prevention practice among nurses.

Methods

Aim

This study aimed to assess the knowledge and practices of nurses regarding HAIs control measures in King Saalman bin Abdul Aziz Medical City at Madinah City.

Study design

A descriptive, cross-sectional design was used in this study.

Study setting

This study was conducted at the King Saalman bin Abdul-Aziz Medical City in Madinah City, which is affiliated with the Saudi MOH. The study covered a period from August 14th, 2022, to October 10, 2022. Include all registered nurses working in KSAMC and It was excluding registered nurses not providing direct care to patients, nurses working on administrative positions and nurses with less than 3 months into their clinical career because they are still on the orientation period.

Sample

A non-probability (convenience) sampling technique was used to select the study participants. A total of 322 nurses participated in this study and responded to the study questionnaire.

Study instrument

NI questionnaires were developed by Alrubaiee et al. (7). A total of 45 closed-ended questions were included in the questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of three parts:

Part I (Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics): Age, gender, marital status, education status, place of work, years of experience, working area and experience with patient had HAIs.

Part II (The assessment of nurses’ knowledge about HAIs control measures): It consists of 30-item divided into 7 dimensions: Hand hygiene domain (5 items), PPE domain (5 items), safe injection practices (4 items), reprocessing of patient care equipment (4 items), routine hospital cleaning (4 items) safe linen handling (4 items), and safe waste handling disposal (4 items).

Part III (The assessment of nurses’ practices about HAIs control measures).

It consists of 15-item divided into two parts: The first part, precautions to prevent HAIs (9 items). The second part, actual actions to prevent HAIs (6 items).

Scoring system

Calculated scores range from 1 to 30 points for knowledge and 1 to 15 points for practices. Nurses were classified as having poor knowledge and practices if they scored below 50%, fair if they scored 50 to 79%, and good if they scored 80% or higher.

Validity and reliability

The study by Alrubaiee et al. (13) found that the NI tool is valid. The suggested tool was taken from a Yemeni study with a comparable focus. The reliability of the study instrument was tested using the Cronbach’s alpha (α) test based on the responses of a pilot sample (26 nurses). The results indicated a Cronbach (α) of 0.75 for the knowledge questionnaire and 0.74 for the practice questionnaire, which is considered acceptable.

The responses were recorded and analyzed using the statistical packages for social sciences (SPSS) version 26 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp, USA) was used to analyze data obtained from this study. Descriptive statistics (numbers and percentages) were used for all qualitative variables while mean and standard deviations were used to present all quantitative variables. The total knowledge and practice scores were compared with the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses by using Mann–Whitney Z-test and Kruskal–Wallis H-test. Pearson correlation coefficient was performed to determine the correlation between the knowledge score and practices. A P-value of 0.05 was used to indicate statistical significance.

Data collection

The self-report questionnaire was utilized in this study to gather information. Data were gathered using a Google Forms electronic questionnaire. A link of the questionnaire was sent from the nursing education department to nurse managers to be distributed to staff nurses included in this study. The data collection process took 2 months: from August 14th, 2022 to October 10 2022.

Ethical consideration

The Institutional Review Board of King Saalman bin Abdul-Aziz Medical City in Madinah City granted ethical permission for the study. In addition, the primary writer was contacted via email for permission to use their tools. Participants in the study are not harmed by it. Data were gathered anonymously, confidentiality was upheld, and no personal information about the subjects was known. Email addresses were not required to view the surveys by participants.

Result

Sociodemographic and professional characteristics of nurses

In total, 322 nurses responded to survey, 26.7% were aged between 31 and 35 years with the female being dominant (79.5%). Regarding marital status, 60.2% were married and 62.1% were bachelor’s degree holders. The most common place of work was Maternity and Children’s Hospital (51.2%). Regarding years of experience, 28% had 1 to 5 years of working as a nurse while 60.2% reported having experience with patients having a HAIs. Of those who indicated experience with HAIs, the most encountered infection was VAP (52.6%) and CAUTI (51%).

Table 1 was initially designed to quantify nurses’ knowledge, some items particularly the ones that are marked (†) also quantify behavioral compliance or correct application of infection control practices in real clinical settings. Therefore, the sum score might be a combination of theoretical knowledge and practical familiarity or compliance with standard precautions.

| Knowledge statement | Correct answer N (%) |

| Hand Hygiene total score (mean ± SD) | 4.57 ± 0.66 |

| 1. Hand hygiene must be performed before and after any contact with the patient | 318 (98.8) |

| 2. When using alcohol-based hand rub, hand rubbing should continue for at least 20–30 sec. | 306 (95.0) |

| 3. Hand hygiene with antiseptic soap and running water should be done when hands are soiled | 305 (94.7) |

| 4. Wash hands immediately before and after wearing gloves of any kind | 284 (88.2) |

| 5. The use of gloves can replace the need for hand hygiene† | 259 (80.4) |

| Personal protective equipment (PPE) total score (mean ± SD) | 3.52 ± 0.72 |

| 6. The mask must be changed if it becomes wet or contaminated | 315 (97.8) |

| 7. Gloves should be changed if they become contaminated or torn during contact with the same patient | 315 (97.8) |

| 8. The nurse can go from patient to patient wearing the same gown† | 278 (86.3) |

| 9. The general sequence of putting on PPE is Hand hygiene, gloves gown, mask, eye protection† | 210 (65.2) |

| 10. Personal protective equipment is the most effective means of preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infections† | 16 (05.0) |

| Safe injection practices total score (mean ± SD) | 2.49 ± 0.82 |

| 11. Used needles should be bent immediately before disposed into a sharps waste container† | 252 (78.3) |

| 12. Change the needle when using the same mixing syringe to reconstitute several vials | 247 (76.7) |

| 13. The peripheral IV cannula should be replaced after 72–96 h as a maximum from its insertion | 238 (73.9) |

| 14. Pre-soak cotton wool in a container with 60–70% alcohol is used to disinfect the skin at the injection site† | 65 (20.2) |

| Total knowledge of preventive measures of person-to-person transmission score (mean ± SD) | 10.6 ± 1.43 |

| Reprocessing of patient care equipment total score (mean ± SD) | 3.45 ± 0.70 |

| 15. Surgical instruments (e.g. Scalpels, forceps, scissors, and clamps) must be sterilized before re-use by another patient | 308 (95.7) |

| 16. Multi-patient uses equipment (e.g. BP cuff, stethoscope, etc.) must be disinfected after each use by patients | 303 (94.1) |

| 17. Semi-critical instruments (e.g. anesthesia equipment, some endoscopies) require cleaning and sterilization or disinfection between uses by patients | 285 (88.5) |

| 18. Under normal conditions, it is enough to clean low-risk tools after each use | 215 (66.8) |

| Routine hospital cleaning total score (mean ± SD) | 3.43 ± 0.61 |

| 19. Patients’ rooms and the bed’s surroundings should be cleaned and disinfected prior to receiving a new patient | 316 (98.1) |

| 20. Telephones, doorknobs, and surfaces like nurse’s counters need a daily disinfection | 309 (96.0) |

| 21. High-risk zones (e.g. burn unit and any area caring for immunocompromised patients) in the hospital should be cleaned and disinfected daily | 304 (94.4) |

| 22. Alcohol solution is used for cleaning blood spillages and other body fluids† | 177 (55.0) |

| Safe linen handling total score (mean ± SD) | 2.71 ± 0.66 |

| 23. Soiled linen should be collected and removed after each procedure daily or as needed | 310 (96.3) |

| 24. Handle the used linen as infectious items even if there is no visible contamination | 291 (90.4) |

| 25. Separation of the used linen in place of use before sending them to the laundry | 238 (73.9) |

| 26. Soiled linen must be carefully rolled into the center and placed in a cloth bag† | 34 (10.6) |

| Safe waste handling disposal total score (mean ± SD) | 2.52 ± 0.96 |

| 27. Infectious hospital waste should be disposed of in a black colored bag† | 279 (86.6) |

| 28. Non-infectious hospital waste should be disposed of in a yellow-colored bag† | 257 (79.8) |

| 29. Separation of hospital waste (infectious and non-infectious) should not be done at a department† | 230 (71.4) |

| 30. The IV bags, tubing, and Foley’s bags are considered high-risk waste† | 46 (14.3) |

| Total Knowledge of preventive measures from hospital environment score (mean±SD) | 12.1 ± 1.68 |

| Total knowledge score (mean ± SD) | 22.7 ± 2.56 |

| Level of knowledge | |

| • Poor | 03 (0.90) |

| • Moderate | 188 (58.4) |

| • Good | 131 (40.7) |

| †Reverse answer. | |

Assessment of nurses’ knowledge about HAIs control measures

The assessment of nurses’ knowledge of HAIs control measures are given in Table 1. The overall score for the knowledge of preventive measures of person-to-person transmission dimension was 10.6 (SD 1.43). The total mean score for the knowledge of preventive measures from the hospital environment was 12.1 (SD 1.68). The overall mean score of the knowledge of HAIs control measures was 22.7 (SD 2.56) wherein 40.7% were considered good knowledge, 58.4% were fair and only 0.9% were considered poor knowledge levels.

Assessment of nurses’ practices regarding HAI control measures

Table 2 presents the assessment of nurses’ practices regarding HAI control measures. The practices were composed of two dimensions such as precautions to prevent HAIs and actual actions to prevent HAIs. The total mean score for the precautions to prevent HAIs was 6.69 (SD 1.19). The total mean score for actual actions to prevent HAIs dimension was 4.03 (SD 0.98). The overall mean score for the practices regarding HAI control measures was 10.7 (SD 1.69) with poor, moderate, and good practices compromising of 3.7, 63.7, and 32.6%, respectively.

| Practices statement | Correct answer N (%) |

| Precautions to prevent healthcare-associated infections total score (mean ± SD) | 6.69 ± 1.19 |

| 1. Be sure to clean the patient’s skin first and then disinfected it with alcohol before giving IM and IV injection | 308 (95.7) |

| 2. I shall clean the top of the multi-use insulin vial with a 60–70% alcohol swab and hand hygiene before each use | 291 (90.4) |

| 3. I shall work under contact precautions all the time when I care for Mrs. Fatima | 288 (89.4) |

| 4. If I had worn gloves to nurse Mrs. Fatima, I do not need to wash my hands immediately after glove removal† | 280 (87.0) |

| 5. I shall follow aseptic technique (HH, wearing clean gloves and site disinfection) for urinary catheter insertion | 280 (87.0) |

| 6. As possible, I shall expose the wound for a minimum time to avoid contamination | 247 (76.7) |

| 7. I shall recap the needle before disposing of the syringe and the needle into the sharps waste container† | 246 (76.4) |

| 8. Conditions such as VRE and MRSA can’t be transmitted through direct contact† | 192 (59.6) |

| Actual actions to prevent healthcare-associated infections total score (mean ± SD) | 4.03 ± 0.98 |

| 9. I shall dispose of the dressing material from Mrs. Fatima in a yellow plastic bag | 296 (91.9) |

| 10. I shall allocate special tools to nurse Mrs. Fatima or clean and disinfect or sterilize this equipment after each use | 292 (90.7) |

| 11. I shall not permit any sick visitor to visit Mrs. Fatima | 210 (65.2) |

| 12. I shall change the wound dressing at least 10 min after bed-making and room-cleaning procedures | 151 (46.9) |

| 13. I shall wear gloves and gowns all the time when in contact with Mrs. Fatima† | 53 (16.5) |

| Total practices score (mean ± SD) | 10.7 ± 1.69 |

| Level of practices | |

| • Poor | 12 (03.7) |

| • Moderate | 205 (63.7) |

| • Good | 105 (32.6) |

| †Reverse answer. (Scenario: Mrs. Fatima is a 60-year-old female. She was admitted to the surgical department on the morning of a planned cholecystectomy surgery. Mrs. Fatima has a history of obesity and diabetes. Post-operatively, it is planned that Mrs. Fatima will have a peripheral IV and a urinary catheter planned for 2 days. Her wound needs a dressing change by her nurse daily. In the department where Mrs. Fatima is staying, one patient on the unit is known to have vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and three other patients are known to have methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). In this scenario, Mrs. Fatima, an elderly female patient with obesity and diabetes, is at increased risk of acquiring nosocomial infections due to her health conditions, the hospital environment, and post-operative care. As her primary nurse, your goal is to prevent her from developing such infections. |

|

Differences in the score of knowledge according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses

When measuring the differences in the score of knowledge according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses (Table 3), it was found that females were more associated with having a better knowledge score than males (Z = 3.869; P < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between knowledge scores in relation to age group, marital status, educational level, place of work, years of experience, and experience with patients having HAIs (P > 0.05).

| Factor | Knowledge Total score (30) Mean ± SD |

Z/H-test | P |

| Age groupa | |||

| • 21–30 years | 22.5 ± 2.61 | H = 2.285 | 0.319 |

| • 31–40 years | 22.7 ± 2.59 | ||

| • > 40 years | 23.2 ± 2.35 | ||

| Genderb | |||

| • Male | 21.6 ± 2.69 | Z = 3.869 | <0.001** |

| • Female | 22.9 ± 2.45 | ||

| Marital statusb | |||

| • Unmarried | 22.8 ± 2.85 | Z = 1.125 | 0.260 |

| • Married | 22.6 ± 2.35 | ||

| Educational level | |||

| • Diploma | 22.3 ± 2.49 | Z = 0.884 | 0.060 |

| • Bachelor or higher | 22.9 ± 2.58 | ||

| Place of worka | |||

| • Medina General Hospital | 22.6 ± 3.11 | H = 2.538 | 0.281 |

| • Maternity and Children’s Hospital | 22.9 ± 2.22 | ||

| • Psychiatric hospital | 22.3 ± 2.38 | ||

| Years of experience as a nursea | |||

| • ≤ 5 years | 22.4 ± 2.69 | H = 2.364 | 0.307 |

| • 6–15 years | 22.9 ± 2.28 | ||

| • >15 years | 22.8 ± 2.87 | ||

| Experienced with patients having healthcare-associated infectionsb | |||

| • Yes | 22.8 ± 2.61 | Z = 0.810 | 0.418 |

| • No | 22.6 ± 2.49 | ||

| aP-value has been calculated using Kruskal–Wallis H-test. bP-value has been calculated using Mann–Whitney Z-test. **Significant at P < 0.005 level. |

|||

Differences in the score of practices according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses

While measuring the differences in the score of practices according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the nurses (Table 4), it was observed that a higher practice score was more associated with females (Z = 4.334; P < 0.001) being employed at Medina General Hospital (H = 20.189; P < 0.001) and experience with patients having HAIs (Z = 2.495; P = 0.013). Other socio-demographic variables did not show significant differences when compared to practice score including age group, marital status, educational level, and years of experience (P > 0.05).

| Factor | Practices Total score (15) Mean ± SD |

Z/H-test | P |

| Age groupa | |||

| • 21–30 8\s | 10.7 ± 1.85 | H = 0.595 | 0.743 |

| • 31–40 years | 10.7 ± 1.61 | ||

| • > 40 years | 10.9 ± 1.58 | ||

| Genderb | |||

| • Male | 10.0 ± 1.78 | Z = 4.334 | <0.001** |

| • Female | 10.9 ± 1.62 | ||

| Marital statusb | |||

| • Unmarried | 10.9 ± 1.68 | Z = 1.692 | 0.091 |

| • Married | 10.6 ± 1.68 | ||

| Educational level | |||

| • Diploma | 10.7 ± 1.48 | Z = 0.648 | 0.517 |

| • Bachelor or higher | 10.8 ± 1.79 | ||

| Place of worka | |||

| • Medina General Hospital | 10.5 ± 1.89 | H = 20.189 | <0.001** |

| • Maternity and Children’s Hospital | 11.1 ± 1.51 | ||

| • Psychiatric hospital | 10.2 ± 1.59 | ||

| Years of experience as a nursea | |||

| • ≤ 5 years | 10.4 ± 2.07 | H = 4.268 | 0.118 |

| • 6–15 years | 10.9 ± 1.42 | ||

| • >15 years | 10.8 ± 1.52 | ||

| Experienced with patients having HAIsb | |||

| • Yes | 10.9 ± 1.66 | Z = 2.495 | 0.013** |

| • No | 10.5 ± 1.71 | ||

| aP-value has been calculated using Kruskal–Wallis H-test. bP-value has been calculated using Mann–Whitney Z-test. **Significant at P < 0.005 level. |

|||

In Table 2, the practices tested are significantly associated with auditing the extent to which healthcare providers comply with infection prevention bundles targeted at multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs). These infection prevention bundles are vital for reducing the incidence of HAIs, specifically among high-risk patients like the case in the provided scenario – Mrs. Fatima, a 60-year-old diabetic and obese female patient undergoing cholecystectomy. Postoperatively, her intraoperative condition, including the placement of a urinary catheter, peripheral IV, and the daily wound dressing, places her at a clinically significantly increased risk for NIs, especially in a hospital environment where patients are already colonized with vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). The assessor emphasizes the significance of quantifying the degree to which nurses practice evidence-based infection control measures that are standard components of MDRO bundles. These include compliance with proper hand hygiene, utilization of PPE, adherence to isolation protocols, and use of aseptic technique during invasive procedures and dressing.

Correlation between knowledge score and practice score

There was a positive significant correlation observed between the knowledge score and practice score (r = 0.336), indicating that the increase in the score of knowledge is correlated with the increase in the score of practices (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Correlation between knowledge score and practices score.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding IPC, namely standard precautions and HAIs. Standard precautions, according to CDC and WHO guidelines, are the core set of 11 evidence-based practices that must be followed by all healthcare professionals to avoid the transmission of infectious agents. These include hand hygiene, PPE use, respiratory hygiene, safe injection practice, and environmental cleaning among others.

The findings showed that the majority of the participants (94.1%) had knowledge of hand hygiene, which was considered the cornerstone of standard precautions. Moreover, 58.7% had adequate knowledge of PPE use, another key component. In total, 58.4% of nurses had a fair level of knowledge of standard precautions, and 40.7% had good knowledge. Interestingly, 55.3% of participants had adequate knowledge of cleaning and disinfecting patient care equipment, also a component of standard precautions.

This study used the term ‘knowledge of HAIs control measures’, which is more appropriate – based on IPC practice – to interpret as compliance with standard precautions. Thus, Table 1 can be also interpreted as an indicator of healthcare workers’ compliance with basic standard precautionary measures. The total knowledge score reflects their awareness and understanding of such practices, a key measure against which infection transmission can be avoided in the health care setting.

In comparison, Alrubaiee et al. (13) found that 87% of Yemeni nurses were unknowledgeable regarding NI prevention, while 4% were very knowledgeable. More advanced qualifications among nurses could account for improved findings within this study – 62.1% of the nurses were bachelor’s degree graduates.

This is also supported by Salem (2019) in Saudi Arabia, with 60% of nurses expressing an adequate awareness of infection control practice, especially for those who had less than 5 years’ experience. In contrast, Elsayed Fawzi et al. (16) in Egypt revealed that 85.3% of nurses did not have any knowledge of infection control procedures, and there were differences that could be termed as a consequence of disparity in the training across institutions.

This research also assessed nurses’ practices that strongly align with their compliance with bundles for specific HAIs. These HAIs include CAUTI, CLABSI, SSI, and VAP and typically occur as a consequence of invasive device use such as urinary catheter, central line, and mechanical ventilator, or following surgery. Compliance with prevention bundles – structured, evidence-based sets of practices – is important to reduce these infections.

Here, Table 2 shows the actual compliance of nurses with HAI prevention practices (bundles). Thus, 63.7% of nurses had fair IPC practices, and 32.6% had good practices. Particularly, 68.6% of nurses had a fair degree of precautionary practices, and 59.6% had fair actual precautions to prevent HAIs. Notably, 34.8% had a good degree of compliance with precautionary practices, while 28.0% had good actual actions, which may indicate gaps in translating knowledge into sustained behavior.

Salem also emphasized the importance of nurses in infection-free healthcare environments, although 51.7% of their study respondents reported poor IPC practice (10). Similarly, Alrubaiee et al. (7) obtained 71% compliance among Yemeni healthcare workers, which is lower than Fashafsheh et al.’s (17) finding at 91.14%. Nonetheless, Elsayed Fawzi et al. (16) and Shrestha and Thapa (18) reported higher poor practice percentages of 29 and 51.8%, respectively.

Interestingly, this study also revealed a strong positive correlation between knowledge and practice scores, in support of the hypothesis that improved knowledge improves compliance with infection prevention protocols. This finding is consistent with Kalantarzadeh et al. (19), who emphasized the role of formal education and training programs in facilitating proper IPC behavior among nurses.

Overall, while most nurses reported good levels of practice and knowledge, there is still room for improvement in following standard precautions and HAI-specific bundles, particularly through on-the-job training, continuous professional development, and routine IPC audits.

References

| 1. | Brosio F, Kuhdari P, Stefanati A, Sulcaj N, Lupi S, Guidi E, et al. Knowledge and behaviour of nursing students on the prevention of healthcare associated infections. J Prev Med Hyg 2017; 58(2): E99–104. doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2017.58.2.744 |

| 2. | Aggarwal A, Mehta S, Gupta D, Tabasi N. Clinical & immunological erythematosus patients characteristics in systemic lupus Maryam. J Dent Educ 2012; 76(11): 1532–39. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR |

| 3. | Petrov I, V. Prevention of healthcare associated infections in the tuberculosis health center. Helix 2018; 8(1): 2958–63. doi: 10.29042/2018-2958-2963 |

| 4. | Lemiech-Mirowska E, Kiersnowska ZM, Michałkiewicz M, Depta A, Marczak M. Nosocomial infections as one of the most importantproblems of the healthcare system. Ann Agric Environ Med 2021; 28(3): 361–6. doi: 10.26444/aaem/122629 |

| 5. | Majidipour P, Aryan A, Janatolmakan M, Khatony A. Knowledge and performance of nursing students of Kermanshah-Iran regarding the standards of nosocomial infections control: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2019; 12(1): 3–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4533-4 |

| 6. | Stone PW. Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: an American perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Res 2009; 9(5): 417–22. doi: 10.1586/erp.09.53 |

| 7. | Alrubaiee G, Baharom A, Shahar HK, Daud SM, Basaleem HO. Knowledge and practices of nurses regarding nosocomial infection control measures in private hospitals in Sana’a City, Yemen. Saf Health 2017; 3: 16. doi: 10.1186/s40886-017-0067-4 |

| 8. | Dellinger EP. Prevention of hospital-acquired infections. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2016; 17(4): 422–6. doi: 10.1089/sur.2016.048 |

| 9. | Collins AS. Preventing Health Care–Associated Infections. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Apr. Chapter 41. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2683/ [cited 2008]. |

| 10. | Salem OA. Knowledge and practices of nurses in infection prevention and control within a Tertiary Care Hospital. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2019; 9: 422–25. |

| 11. | Alhumaid S, Al Mutair A, Al Alawi Z, Alsuliman M, Ahmed GY, Rabaan AA, et al. Knowledge of infection prevention and control among healthcare workers and factors influencing compliance: a systematic review. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021; 10(1): 86. doi: 10.1186/s13756-021-00957-0 |

| 12. | Hammoud S, Khatatbeh H. Research article a survey of nurses’ awareness of infection control measures in Baranya County, Hungary. Nurs Open 2021; 8(6): 3477–83. doi: 10.1002/nop2.897 |

| 13. | Alrubaiee G, Baharom A, Shahar HK, Daud SM, Basaleem HO. Knowledge and practices of nurses regarding control measures in nosocomial infection ivate hospitals in Sana’a City, Yemen. Saf Health 2017; 3(1): 1–6. doi: 10.1186/s40886-017-0067-4 |

| 14. | Chisanga CP. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of nurses in infection prevention and control within a Tertiary Hospital in Zambia. Masters of Nursing Science, In the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University; 2017. |

| 15. | Jahangir M, Ali M, Riaz MS. Knowledge and practices of nurses regarding spread of nosocomial infection ingovernment hospitals, Lahore. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci 2017; 16(03): 149–53. doi: 10.22442/jlumhs.171630524 |

| 16. | Elsayed Fawzi S, Fathi Sleem W, Saleh Shahien E, Abdullah Mohamed H. Assessment of knowledge and practice regarding infection control measures among staff nurses. Port Said Scientific Journal of Nursing 2019; 6(1): 83–100. doi: 10.21608/pssjn.2019.34038 |

| 17. | Fashafsheh Ahmad Ayed I, Eqtait Lubna Harazneh F. Knowledge and Practice of Nursing Staff towards Infection Control Measures in the Palestinian Hospitals. Journal of Education and Practice 2015; 6(4): 79–91. |

| 18. | Shrestha GN, Thapa B. Knowledge and Practice on Infection Prevention among Nurses of Bir Hospital, Kathmandu 2018; 16(3): 330–5. |

| 19. | Kalantarzadeh M, Mohammadnejad E, Ehsani SR, Tamizi Z. Knowledge and practice of nurses about the control and prevention of nosocomial infections in emergency departments. Archives of Clinical Infectious Diseases 2014; 9(4): 0–4. doi: 10.5812/archcid.18278 |