ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Patient hand hygiene experiences in a primary care centre in Ireland during COVID-19

Anne-Marie Kinsella* and Pauline O’Reilly

Department of Nursing and Midwifery & Health Research Institute, University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland.

Abstract

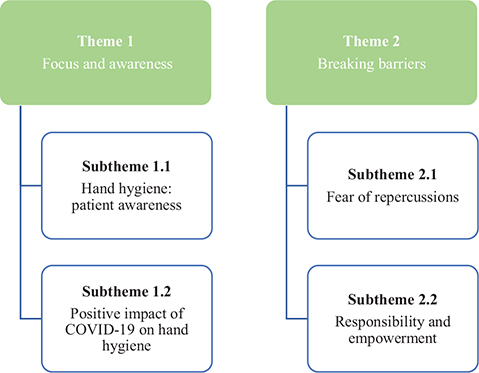

The implementation of proper hand hygiene (HH) has been shown to reduce the risk of developing healthcare-associated infections. There is an increased awareness of the importance of HH since the onset of COVID-19. This study used an interpretive descriptive qualitative design to explore patients’ experiences of healthc workers’ (HCWs’) HH practices in a primary care centre in Ireland during COVID-19. The data were collected from 12 participants using in-depth, semi-structured interviews and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Two themes were constructed, each with two subthemes. Theme 1, ‘Focus and Awareness’, had the subthemes ‘Hand Hygiene and Patient’s Awareness’ and ‘Positive Effects of COVID-19’. Theme 2, ‘Breaking Barriers’, had the subthemes ‘Fear of Repercussions’ and ‘Responsibility and Empowerment’. Patients believed they should have a role when it comes to ensuring correct HH is performed during their episode of care. Barriers to this included the perceived reaction of HCWs to the feedback and a lack of knowledge of the five moments of hand hygiene.

Keywords: health personnel; primary care; hand hygiene; patient-reported outcomes; cross-infection prevention and control; COVID-19; Ireland

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2024, 20: 23147 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v20.23147

Copyright: © 2024 Anne-Marie Kinsella and Pauline O’Reilly. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 4 May 2023; Published: 13 November 2024

Competing interests and funding: The authors state that no funding was involved, and there was no conflict of interest.

*Anne-Marie Kinsella, Station Road Primary Care Centre, Station Road, Ennis, Co. Clare, Tel.: +353 (0)65 6865230, Tel.: +353 (0)61 202700. Email: annief.kinsella@hse.ie

It has been stated that antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is potentially one of the greatest threats to human health over the last decade (1). Correct hand washing/rubbing technique and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘five moments of hand hygiene’ have been shown to be effective at reducing the risk of developing these infections (2–6). The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of correct hand hygiene (HH) technique (5–6). Healthcare workers (HCWs) continue to fail to follow the HH guidelines (7–10). It has been suggested for almost two decades that patients should have a role when it comes to assisting HCWs to ensure that correct HH is performed (11). This is influenced first by the HCW’s willingness to accept the patients’ role and, second, by the patients’ knowledge of correct HH procedures (6). This study aimed to look at patient experiences, beliefs and attitudes of HCWs’ HH practices in a primary care centre (PCC) in Ireland. A PCC is a purpose-designed building that provides a single location for a primary care team to work from and includes, for example, nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and speech and language therapy (12).

Background

It has been recognised that at any one time, there are more than 4.3 million patients affected with a healthcare-associated infection (HCAI) in the European Union and European Economic Area annually. This leads to over 90,000 deaths (13). The result of this is an economic burden of €13–24 billion (14). WHO has defined a HCAI as:

…an infection occurring in a patient during the process of care in a hospital or other health-care facility which was not present or incubating at the time of admission. This includes infections acquired in the health-care facility but appearing after discharge, and also occupational infections among health-care workers of the facility. (15)

HCAIs result in extra distress for patients in the form of lengthened stay in hospital, resistance of microorganisms, long-term disability and unnecessary deaths. There is estimated to be a significant monetary cost incurred due to HCAIs after people are discharged from hospital. In Ireland, HCAIs affect on average one in 25 people in long-term care facilities (16).

The rise of AMR microorganisms has significantly impacted the challenges faced in the prevention and control of infection within health systems globally. The consumption of antimicrobial medication in the Irish community is higher than the European average (17). Consequently, it is important to follow measures that prevent the spread of HCAI. Infection prevention and control (IPC) is an evidence-based approach to preventing and controlling the spread of infection within a healthcare service (16, 18). Standard precautions are the minimum IPC practices that are relevant to all patient care. They were first introduced as universal precautions in 1985 by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), mostly in response to the human immune-deficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. Standard precautions are a risk assessment, based on evidence-based practices created to protect the patient and HCW by stopping the spread of infection (19). There are national and international guidelines supporting the use of these in IPC (20, 21). HH and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) such as glove wearing are examples of standard precautions in IPC. Gloves are worn when there is a risk of contact with blood or bodily fluids.

In Ireland during 2019, a substantial amount of funding was put into IPC teams in acute and community settings as this was seen to be a key for ensuring a sustainable response to HCAIs (1). Ireland’s second One Health National Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance 2021–2025 (iNAP2) continues to place emphasis on IPC with a focus on enhancing HCW, patient and public involvement in the area (1).

Patients have the right to expect that those providing their care meet appropriate standards of hygiene and follow the guidelines to lower the risk of spreading HCAIs. IPC should be routinely included in delivery of care to people (1, 16, 20). HH has been shown to be one of the most effective means of defence against HCAIs. It reduces morbidity and mortality by reducing the transmission of healthcare-associated pathogens (2–6). HH is a general term that refers to any action of hand cleansing and, if done properly, can be up to and over 90% effective in preventing infection spread (22). It has been shown to have prevented countless people and HCWs globally from contracting Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (5). In 2007, the model for the ‘My five moments for hand hygiene’ was developed. The model describes reference points for HCWs to perform HH during a treatment episode. These points are found at critical times when HH is required to stop microbial transmission (23), see table 1.

| Moment | Example |

| 1. Before patient contact | Shaking hands; helping patient move; taking patient’s vitals |

| 2. Before aseptic technique | Oral care; wound dressings; subcutaneous injections |

| 3. After blood or bodily fluids | Oral care; subcutaneous injection; clearing up bodily fluid spillages |

| 4. After patient contact | Shaking hands; helping a patient move |

| 5. After contact with patient surroundings | Any contact with patient surroundings in the home |

| *Adapted from Sax et al. (23). | |

There has been shown to be an overuse and misuse of gloves by HCWs resulting in reduced adherence to the moments of HH (24, 25). This reduction has been noticed in particular between procedures on the same patient. HCWs have been found to have better HH compliance after glove use and reduced compliance before glove use (25, 26).

All HCWs should receive education and training on standard precautions (20, 27, 28). It is mandatory for all HCWs in Ireland to attend HH training at least every 2 years, and it is incumbent on them to implement the standard precautions guidelines (22, 29). The revised HH guidelines are aimed at all HCWs but are relevant to patients, carers, visitors and the public (27).

The focus of the first WHO global safety challenge was on HCAI with a shared vision of ‘clean care is safer care’ (11). This alliance had six actions, one of which was ‘patients for patient safety’ in which their goal was to get patients and patient organisations to participate in patient safety globally (30). Global groups continue to advocate for patient safety with the goals of: engaging and empowering patients, families and communities to play an active role in their own care, bringing the voices of patients and people to the forefront of health care, and creating an enabling environment for partnerships between patients, families, communities and health professionals (31). Educating patients is seen as a means of empowering them to play an active role in their care regarding the reduction of HCAIs. The Government of Ireland Department of Health has stated that they are, ‘committed to engaging and involving patients and people in their own health and wellbeing, and care and treatment’ (32).

In Ireland, the National Standards for Safer Better Health Care, the National Health Care Charter, National Hand Hygiene Guidelines and National Standard for IPC in Community Services provide information and guidelines on how HCWs and service users can help to ensure delivery of safe and effective services (16, 27, 33, 34). Patients are encouraged to play a role in asking and reminding HCWs to perform HH. The CDC recommends they ask every time the HCW enters the room and when they remove their gloves (35). The WHO recommends that patients should see HCWs practicing HH before providing care and carrying out observations and examinations, and for wound and catheter care (36).

It has been demonstrated that patients believe they are at higher risk of acquiring an infection if appropriate HH is not performed (37–40). Studies have been conducted to determine if patients feel they have a role in reminding their HCW to perform HH (40–42). Most studies agree patients feel they should have a role; there is no consensus on the best way to educate patients regarding HH or ensuring HCWs accept this relationship (40, 42–44). Education in the five moments of HH appears to be aimed at HCWs; however, the WHO (45) has an information leaflet for patients regarding the moments of HH and when they should expect to see them in throughout their episode of care.

For years, studies have explored ways to improve patient engagement in healthcare including ensuring HH is performed (24, 26, 39, 40–42). Barriers include the patient’s fear of being labelled difficult, a desire for clinician approval and protecting their personal safety (46). It has been suggested these challenges can be overcome by educating the HCW and the patient and improving communication to ensure a more collaborative relationship (47).

The majority of studies have looked at HH compliance in the acute setting (48–51). A search was completed to source articles that offered information regarding HH compliance of HCWs in primary care settings. Several studies demonstrated HCWs in primary care had the knowledge of IPC and HH (7–10, 52). Even though the HCWs were aware of the five moments of HH, it was not associated with positive HH behaviour. Reasons for non-compliance included the belief that community patients were low risk for acquiring infection and uncertainty about the efficacy of the IPC guidelines (7–10).

Our study aimed to explore the experiences of patients attending a PCC in Ireland in relation to HCW HH practices and patients’ perceived role in HCW HH practices.

Methods

Design

This study aimed to explore the beliefs, attitudes and experiences of patients regarding the HH practices of HCWs at a PCC in Ireland. The interviews were carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic from January 2022 to March 2022.

A qualitative interpretive descriptive design was chosen for the study. This study focused on patients attending a PCC in Ireland. The study design aligned with constructivist and naturalistic orientations of inquiry by exploring patient experiences of HH in a clinical setting and seeking patient views about their role in HH throughout their episodes of care (53). This alignment takes into consideration the theoretical and practical knowledge of the researcher who is a HCW in primary care (54). Ethical approval was obtained from a relevant research ethics committee. The conduct and reporting of the study were guided by the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (55) as outlined in Appendix 1.

Study participants had been exposed to HH practices through previous episodes of care within the PCC; it was therefore decided to adopt a non-probability sampling method using a purposive sample. This type of sampling was appropriate because it involves the deliberate choice of participants due to qualities they possess (56). Information packs including an invitation letter, a participation information sheet, an informed consent form and a return envelope were provided by a gatekeeper. The gatekeeper was an administrative staff member at the PCC.

The inclusion criteria included adult patients aged ≥ 18 years attending a PCC who spoke English and had the capacity to provide informed consent. Seventeen patients who attended the PCC for an episode of care were provided with the information pack. The envelope and consent form to be contacted were returned to the principal investigator (PI). The consenting participants were phoned, and their availability confirmed to obtain written-informed consent and conduct the interview.

The PI was a senior physiotherapist working in the PCC who had been trained to provide regular HH training and auditing to HCWs. The second author was a senior lecturer in the Department of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Limerick. As this study was part of an MSc project, she was a supervisor of the PI and of the study. A reflexivity exercise was completed by the PI prior to data collection to allow them to reflect on the topic and where they would place themselves in relation to it both personally and professionally, and in more general terms. It is important for researchers to understand their own perspective to ensure good quality analysis (57).

No remuneration was advertised or offered.

Data collection

Following written consent, data were collected using face-to-face, semi-structured individual interviews of approximately 30 min duration. These types of interviews are the most frequent qualitative data source in health services research (58). All interviews were facilitated by the PI.

For this particular interview guide, four specific areas were explored: general HH, moments of HH, glove wearing and the role of the patient (Appendix 2). Each topic had its own guiding question to be asked of the participant. It was important to establish a general understanding of what the participant knew about HH and their personal experience with it. The first question was intentionally broad to allow the participant to elaborate on their understanding of the concept. The second question was specific to their experience in a primary care setting. The second topic area, moments of HH, had a question aimed at assessing the participant’s understanding of the WHO recommended guidelines for HH. If the participant was unaware of the five moments, the PI explained them verbally. The third topic area of glove wearing had a question aimed at assessing the participant’s perception of glove use during healthcare interventions. The fourth topic area was the role of the patient, where participants’ perception of the patient’s role in ensuring correct performance of HH was explored. The interview guide was developed and piloted prior to the interviews.

Due to COVID-19, social distancing and IPC guidelines were adhered to throughout the interview process. All interviews were audio recorded digitally. Participants were given the opportunity to terminate the interview at any time to ask questions or provide additional information at the end. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and orthographically by the PI, and checked for accuracy. Minor speech hesitations were omitted to ensure ease of readability. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, identifying details were changed or omitted (57).

Data analysis

Data were analysed thematically using an approach from Braun and Clarke (57). As the researcher aimed to capture the participants’ own experience of HH in the community healthcare setting, the data were analysed from a realist essential perspective. Reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) was chosen because the researcher had their own experiences of HH in the community setting from a HCW and a patient’s perspective. The analysis process was iterative. The transcripts were grouped into categories and analysed thematically. Both authors verified the codes, subthemes and themes of the datasets throughout the study. Regular meetings were held between both authors to discuss and agree the final themes.

Due to the nature of the study, an interpretive qualitative approach was used (57). To ensure rigour, two researchers coded a number of the transcripts independently.

Results

Twelve patients were interviewed as theoretical saturation was achieved with this number of participants (59). All participants were female. The age range of the participants was 20–84 years.

Following thematic analysis, two themes were constructed with each having two subthemes. Theme 1 related to patient awareness of what HH meant to them, the importance of the moments of HH and the impact of COVID-19 on HH experiences. This was not included in the original interview schedule; however, it emerged as a subtheme because of the timing of the pandemic. Theme 2 related to how participants felt about offering their HCW feedback regarding missed opportunities for HH and what could be done to assist this process. The findings are presented in Figure 1.

Theme 1: Focus and awareness

The subthemes within this theme relate to participant awareness of HH and the positive impact of COVID-19 on this, see table 2.

Subtheme 1.1. Hand hygiene: patient awareness

When asked about what comes to mind when thinking about the term HH, the participants were mostly consistent with expressions such as clean hands, wash hands and sanitising. Patient safety, the avoidance of cross contamination, infection control and a way to protect each other were mentioned by several of the participants. Almost all commented on the effect COVID-19 has had on their own and others’ HH habits as noted in Subtheme 1.2:

not passing on infection… protecting each other. (p. 10)

Most participants had not heard of the five moments of HH, with several confusing them for the hand washing technique. For those who had heard of them, they were unable to name all five moments. The majority of participants agreed they were something they felt were important and should be known.

Yeah, you know to be able to look out for it, and I think it would be no harm for them [HCWs] to say I’m washing my hands now…… to make you aware…. (p. 4)

When asked about their thoughts on HCWs using gloves during an episode of care, most indicated they would prefer gloves were not worn unless they were used appropriately. There appeared to be some misunderstanding for a few that sanitising whilst wearing gloves was appropriate, as they had seen HCWs doing this. Some participants indicated they would feel safer if gloves were worn, but qualified this statement by adding appropriate use of gloves would be required. It was noted by one that there was a discrepancy between HCWs and the number of times they changed their gloves during an episode of care. One participant mentioned the rationale of glove wearing also keeps the HCW safe when required.

They [the HCW] had sanitised six times both with and without the gloves. (p. 6)

Most participants stated they felt there is a higher risk of acquiring an infection in a hospital, and the most common reason provided included the busyness of the hospitals. PCCs were seen to pose less risk as they are smaller and less busy.

The hospital is more of a rushed environment and people are moving around and going from place to place. Primary care, people have appointments, they’re [HCWs] prepared for who is coming in, who they are meeting. In the hospital you could have emergencies, a lot of visitors, so it’s a whole different environment for infection. (p. 2)

Positive impact of COVID-19 on hand hygiene. Participants reported they were more aware of HH since the onset of COVID-19, with one mentioning they had not realised previously how important HH was. Some mentioned an increased emphasis has been put on the patient performing HH in the centres. The correct hand washing technique appeared to be known and was reportedly being carried out by the participants for the most part. It was felt by the majority that HCWs are performing HH more since the onset of COVID-19. Two participants indicated that they would feel more empowered now to offer feedback to their HCW.

More awareness, like I think Covid has definitely improved this, and I think people are more aware of the importance of it because it’s everywhere now, it’s not just in health care settings. (p. 12)

Hand sanitiser dispensers were noted to be plentiful, and most participants look out for them in places. A couple did voice concerns regarding the safety of them as they suspected they had the potential to be a breeding ground for pathogens if not cleaned:

They could be a very bad place for germs if they’re not kept clean. (p. 1)

Theme 2: Breaking barriers

Within this theme are examples of patients’ fears about what would happen if they requested their HCW perform HH, and where the responsibility lies regarding education, see table 3.

Subtheme 2.1: Fear of repercussions

When asked how they would feel about asking a HCW to perform HH, concerns were expressed around not wanting to insult the HCW as they felt it might be seen as a criticism. A cultural reference was made where being Irish reduces the likelihood of someone requesting HH is performed, due to the patient wanting to avoid making the HCW feel awkward. It was also mentioned that the older generation would not be inclined to query a HCW.

It would take a lot of guts to come out with it, you’d be thinking was it, you might be thinking they’d be saying who does she think she is telling me that I should be washing my hands, so it would take an awful lot to say it… no I don’t think even if I had to say it I would say it. (p. 2)

The concern for most of the participants themselves was a fear of retribution and their care being compromised.

Would be terrified of upsetting people because it’s my care they might take... And we don’t want them to take the hump…. You know, that old expression of, you know I’ll get her back sort of thing. (p. 6)

Two reported they had experience with offering feedback and were met with mixed reactions from the HCW. One advised they would avoid the situation, if necessary, by staying away from that particular HCW in the future.

Subtheme 2.2: Responsibility and empowerment

A few felt HCWs should know how and when to perform HH themselves, and it should not be the responsibility of the patient to remind them.

Yeah I think like in the sense of if, it would be lovely in an ideal world, if you felt totally comfortable to say it to somebody, listen did you wash your hands, I didn’t notice you wash your hands. And to feel like they would say sorry, or [say] I did but you just didn’t notice… you mightn’t want that responsibility… you know I’m the patient here, I’ve other things on my mind. (p. 8)

Most participants advised that the way in which the request was imparted was important. It was felt it would be received more positively if it was said in a nice way, time might need to be spent planning this beforehand.

The majority of participants reported that they would be more likely to request HH be performed by those who are more familiar with or someone that who they believed would take the message positively. Some felt the younger generation would have no problem requesting HH being performed.

Most of the participants believed that being given permission by the HCW to ask would make them feel more empowered to do so.

…I think it should be said to you... because then you’re more likely to say would you actually clean your hands there so. (p. 3)

Suggestions and opinions on how to educate patients regarding the five moments of HH varied. These included posters, leaflets, banners, pamphlets and television advertisements. There were mixed feelings on the use of posters as issues with language and eyesight could make them difficult to understand. It was felt by some patients that there are too many posters displayed in the PCCs, resulting in people not looking at them. Others felt posters in the waiting areas resulted in information being absorbed whilst waiting. It was proposed that leaflets could be used to set HH expectations for patient care, and that these could be used by the patient as a reference following the episode of care. Education received verbally, with or without the use of the other tools mentioned, was the most popular suggestion provided. Concern was expressed by some regarding what to do with this knowledge if the HCW did not follow the five moments.

…could in a way backfire because people now have this knowledge that oh they haven’t done that and now I’m panicked. (p. 8)

Discussion

This study identifies patients experiences of HH in a PCC. Male participants were invited to participate and provided with the information packs. However, they did not return the forms to the gatekeeper.

Study participants demonstrated that there was an awareness of HH, which had been heightened since the onset of COVID-19. This aligned with studies by Haque et al. (5) and Mitra et al. (6). Hand washing/rubbing technique is known, but most are unaware of the five moments of HH. The majority agreed these moments seemed important and felt they were something patients should be familiar with.

Gloves were still seen by some participants as offering an extra layer of protection; however, the majority did not feel comfortable with gloves being used in general episodes of care, unless being used appropriately. It is promising to see that the majority of participants preferred their HCW not to use gloves unless indicated. Patients are unlikely to question their HCW’s rationale for choosing to wear gloves. Due to the lack of knowledge of the moments of HH, patients are unlikely to know when glove use is appropriate and how often gloves should be changed in their episode of care.

All participants in the study agreed that they should have a role in reminding their HCW if they had missed performing HH; however, they were reticent in doing so. This was highlighted in a study where there was a discrepancy regarding the importance patients expressed regarding asking and their intention of asking their HCW to perform HH (60).

Feelings of discomfort were expressed by patients at the thought of asking their HCW to perform HH, with some people not wanting the HCW to feel they were not doing their job correctly. This resonated with previous studies where patients would be happy to offer feedback once the HCW welcomed it and would not see it as a personal challenge (40, 60–62). Similar to other studies (24, 26, 60), participants reported fears of repercussions involving reduced or compromised care and a concern of a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship between them and the HCW.

HCWs have been reported to have mixed views when it comes to being reminded of HH; they may not want to be seen negatively by their patients, expressing embarrassing feelings when prompted to perform HH (63). Historically within health care, there is a patient-provider relationship, which has a power imbalance, with the HCW being dominant. If there was to be optimal patient involvement, it would disrupt this balance with a reduction in the control HCWs have over their patients. It has been recommended further studies are needed to help determine what strategies may be most useful in clarifying patients’ role in IPC, including addressing the power imbalances present, ways to encourage patients’ to question their HCWs about their HH and how patients’ could feel empowered to speak up if required (60, 62, 63).

This study demonstrates that the language used by patients requesting HH to be performed by a HCW is important; being polite and using ‘please’ and ‘thank you’ were noted. It has been shown that HCWs also place importance on this (63). Patient motivational dialogue (PMD) has been trialled, and it was found to result in an increase in patients asking at least once for the HCWs to wash their hands. It is thought the actions were not sustained due to the reaction of the HCWs. This resulted in a suggestion that encouraging patients to ask should be part of the HH curriculum (26).

Being given verbal permission by the HCW to offer feedback was seen to be the most effective way to ensure the patient felt empowered to do so. Previous studies of patients and HCWs recommended supporting an ‘it’s ok to ask’ attitude as the best means to ensure patient involvement (39). It is believed that empowering service users to become involved in this process would help to reduce HCAI as a result of poor HH (39, 42, 64).

HCWs should be encouraged to remind patients to ask them to undertake HH techniques (26). Currently, this is not included within the Irish curriculum (22, 29).

It has also been recognised that public knowledge and perception of the Department of Health have transformed since the start of the pandemic (1). By capitalising on this momentum and the increased patient awareness of the importance of HH, now could be an opportune time to educate patients on the five moments of HH.

Conclusion

Patients have an increased awareness of HH since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This awareness for most stops at the hand washing technique. Awareness of the five moments of HH is lacking, resulting in patients not knowing when they should see their HCW perform HH. Even though patients see HH as being an effective tool in reducing their risk of acquiring an HCAI, a reluctance remains to challenging HCWs on this. This is mostly as a result of the way they perceive the HCW may react to the request. The participants who were inclined to ask their HCWs to perform HH were unaware of the most part of five moments of HH; without this knowledge, they would not know the appropriate times to ask.

What this study adds

Patients using primary care services in Ireland believe they should have a role in ensuring that correct HH is performed during their episodes of care.

Since COVID-19, patients’ knowledge of the hand washing/rubbing technique has improved. Glove use is mostly seen as a negative by patients, unless used appropriately.

The majority of patients are unaware of the five moments of HH. For their role to be effective, they would need to be educated regarding these. It has been suggested that verbal and some written education regarding the moments of HH would be beneficial.

Verbal permission needs to be offered by the HCW at the start of the episode of care to encourage the patient to enact this role.

Recommendations

More research studies are required to be undertaken, which address patients’ involvement and empowerment in relation to IPC, within the PCC setting.

It is important that HCWs encourage and remind patients that it is ok to ask HCWs about HH. HCWs could be reminded of this at the mandatory HH training sessions they attend.

Patients within the primary care setting need to receive information on HH processes.

Limitations of the study

All participants in the study were female.

Although the PCC was representative of most PCCs in Ireland, this study reflects the findings from only one PCC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants interviewed and the general manager of the service for granting permission to recruit the participants.

Ethics approval

Ethical clearance was obtained from a relevant research ethics committee, and permission was sought from the General Manager of the PCC.

References

| 1. | Department of Health, Republic of Ireland. Statement of strategy 2021–2023. 2021. [updated 8 Jun 2021]. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/organisation-information/0fd9c-department-of-health-statement-of-strategy-2021-2023/#:~:text=The%20Statement%20of%20Strategy%20is%20in%20line%20with,in%20the%20right%20place%20at%20the%20right%20time [cited 29 March 2022]. |

| 2. | Lemass H, McDonnelll N, O’Connor N, Rochford S. Infection prevention and control for primary care in Ireland: a guide for general practice. 2014. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/microbiologyantimicrobialresistance/infectioncontrolandhai/guidelines/File,14612,en.pdf [cited 9 December 2020]. |

| 3. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality standard [QS61], quality statement 3: hand decontamination. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs61/chapter/quality-statement-3-hand-decontamination [cited 1 December 2020]. |

| 4. | World Health Organisation. Guidelines on hand hygiene in health care first global patient safety challenge clean care is safer care. 2009. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241597906 [cited 9 December 2020]. |

| 5. | Haque M, McKimm J, Sartelli M, Dhingra S, Labricciosa FM, Islam S, et al. Strategies to prevent healthcare-associated infections: a narrative overview. Risk Manage Healthc Policy 2020; 13: 1765–80. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S269315 |

| 6. | Mitra M, Ghosh A, Pal R, Basu M. Prevention of hospital-acquired infections: a construct during COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Med Prim Care 2021; 10(9): 3348. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_742_21 |

| 7. | Cole M. Infection control: worlds apart primary and secondary care. Br J Community Nurs 2007; 12(7): 301–6. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2007.12.7.23821 |

| 8. | Maroldi MA, Felix AM, Dias AA, Kawagoe JY, Padoveze MC, Ferreira SA, et al. Adherence to precautions for preventing the transmission of microorganisms in primary health care: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs 2017; 16(1): 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12912-017-0245-z |

| 9. | Hilt N, Hulscher ME, Antonise-Kamp L, OldeLoohuis A, Voss A. Current practice of infection control in Dutch primary care: results of an online survey. Am J Infect Ctrl 2019; 47(6): 643–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.11.010 |

| 10. | Bedoya G, Dolinger A, Rogo K, Mwaura N, Wafula F, Coarasa J, et al. Observations of infection prevention and control practices in primary health care, Kenya. Bull World Health Organ 2017; 95(7): 503. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.179499 |

| 11. | World Health Organisation, World Alliance for Patient Safety. Global patient safety challenge, 2005–2006. Available from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/events/05/GPSC_Launch_ENGLISH_FINAL.pdf?ua=1 [cited 10 October 2020]. |

| 12. | Department of Health, Republic of Ireland. Primary care policy. 2019. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/policy-information/831bfc-primary-care/#:~:text=Primary%20care%20centres%20are%20modern,an%20important%20part%20of%20Sl%C3%A1intecare [cited 14 April 2023]. |

| 13. | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals. Stockholm, ECDC; 2024. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/healthcare-associated-point-prevalence-survey-acute-care-hospitals-2022-2023.pdf [cited 1 October 2024]. |

| 14. | World Health Organisation. Patient safety solutions: infection prevention and control. 2012. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-%28ihs%29/psf/curriculum-guide/resources/ps-curr-handouts/course09_handout_infection-prevention-and-control.pdf [cited 10 December 2020]. |

| 15. | World Health Organisation. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. 2011. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/report-on-the-burden-of-endemic-health-care-associated-infection-worldwide [cited 29 March 2022]. |

| 16. | Health Information and Quality Authority, Republic of Ireland. National standards for infection prevention and control in community services. Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), Dublin: Regulation Directorate; 2018. |

| 17. | European Centre for Disease Control. Country visit to Ireland to discuss policies relating to antimicrobial resistance; mission report. 2020. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/country-visit-ireland-discuss-policies-relating-antimicrobial-resistance [cited 29 March 2022]. |

| 18. | World Health Organisation. Infection preventon and control. 2022 Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/infection-prevention-and-control [cited 1 April 2022]. |

| 19. | Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Standard precautions for all patient care. 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/standard-precautions.html [cited 5 December 2020]. |

| 20. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Healthcare-associated infections: prevention and control in primary and community care. 2012 [updated 15 February 2017]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg139/chapter/1-Guidance#standard-principles [cited 9 December 2020]. |

| 21. | Health Service Executive, Republic of Ireland. Standard precautions version 1.0, 28 April 2009. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/microbiologyantimicrobialresistance/infectioncontrolandhai/standardprecautions/File,3600,en.pdf [cited 10 October 2020]. |

| 22. | Health Service Executive, Republic of Ireland. Hand hygiene: preventing avoidable harm in our care. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/hcai/hand-hygiene-in-irish-healthcare-settings/training/hand-hygiene-trainer-programme.pdf [cited 1 April 2022]. |

| 23. | Sax H, Allegranzi B, Uckay I, Larson E, Boyce J, Pittet D. ‘My five moments for hand hygiene’: a user-centred design approach to understand, train, monitor and report hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect 2007; 67(1): 9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.06.004 |

| 24. | Butenko S, Lockwood C, McArthur A. Patient experiences of partnering with healthcare professionals for hand hygiene compliance: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 2017; 15(6): 1645–70. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003001 |

| 25. | Picheansathian W, Chotibang J. Glove utilization in the prevention of cross transmission: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth 2015; 13(4): 188–230. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2015-1817 |

| 26. | Grota PG, Eng T, Jenkins CA. Patient motivational dialogue: a novel approach to improve hand hygiene through patient empowerment in ambulatory care. Am J Infect Ctrl 2020; 48(5): 573–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.11.024 |

| 27. | Royal College of Physaicians of Ireland and Health Service Executive, Republic of Ireland. Guidelines for hand hygiene in Irish healthcare settings: update of 2005 guidelines. 2015. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/microbiologyantimicrobialresistance/infectioncontrolandhai/handhygiene/publications/File,15060,en.pdf [cited 25 November 2020]. |

| 28. | Health Information Quality Authority, Republic of Ireland. National standards for the prevention and control of health care associated infections. 2009 [draft standards updated 2017]. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-05/2017-HIQA-National-Standards-Healthcare-Association-Infections.pdf [cited 31 March 2022]. |

| 29. | Health Service Executive, Republic of Ireland. 2 Community infection prevention and control manual: a practical guide to implementing standard and transmission-based precautions in community health and social care setting. 2022. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10147/631787 [cited 1 April 2022]. |

| 30. | Pittet D, Donaldson L. Clean care is safer care: the first global challenge of the WHO World Alliance for Patient Safety. Infect Ctrl Hosp Epidemiol 2005; 26(11): 891–4. doi: 10.1086/502513 |

| 31. | World Health Organisation. Patients for patient safety. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/patients-for-patient-safety#:~:text=WHO%20Patients%20for%20Patients%20Safety%20%28PFPS%29%20is%20a,policy- [cited 12 April 2022]. |

| 32. | Department of Health, Government of Ireland. Ireland’s one health national action plan on antimicrobial resistance 2021–2025 (known as iNAP2). Government of Ireland; 2021, p. 24. Available from: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/d72f1-joint-action-on-antimicrobial-resistance/ [cited 1 April 2022]. |

| 33. | Health Information Quality Authority, Government of Ireland. National standards for safer better healthcare. 2012. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/reports-and-publications/standard/national-standards-safer-better-healthcare [cited 29 March 2022]. |

| 34. | Health Service Executive, Government of Ireland. Guidelines on infection prevention and control for Cork & Kerry Community Healthcare [updated 2017]. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/infectcont/sth/gl/sec3.html [cited 6 December 2020]. |

| 35. | Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients hand hygiene. 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/handhygiene/patients [cited 12 April 2023]. |

| 36. | World Health Organisation. Hand hygiene promotion in health care tips for patients. 2013. Available from: https://tips-for-patients.pdf (who.int) [cited 12 April 2023]. |

| 37. | World Health Organisaiton. Alliance for patient safety hand hygiene survey results from phase one. 2007. Available from: https://www.who.int/patientsafety/hand_hygiene_survey_phase1.pdf?ua=1 [cited 10 October 2020]. |

| 38. | Flannigan K. Asking for hand hygiene: are patients comfortable asking, and, are healthcare providers comfortable being asked? Can J Infect Ctrl 2015; 30(2): 105–9. |

| 39. | Pittet D, Panesar SS, Wilson K, Longtin Y, Morris T, Allan V, et al. Involving the patient to ask about hospital hand hygiene: a National Patient Safety Agency feasibility study. J Hosp Infect 2011; 77(4): 299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.10.013 |

| 40. | Longtin Y, Sax H, Allegranzi B, Hugonnet S, Pittet D. Patients’ beliefs and perceptions of their participation to increase healthcare worker compliance with hand hygiene. Infect Ctrl Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30(9): 830–9. doi: 10.1086/599118 |

| 41. | McGuckin M, Govednik J. Patient empowerment and hand hygiene, 1997–2012. J Hosp Infect 2013; 84(3): 191–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.01.014 |

| 42. | McGuckin M, Storr J, Longtin Y, Allegranzi B, Pittet D. Patient empowerment and multimodal hand hygiene promotion: a win-win strategy. Am J Med Qual 2011; 26(1): 10–17. doi: 10.1177/1062860610373138 |

| 43. | Schweizer ML, Reisinger HS, Ohl M, Formanek MB, Blevins A, Ward MA, et al. Searching for an optimal hand hygiene bundle: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(2): 248–59. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit670 |

| 44. | Gould DJ, Moralejo D, Drey N, Chudleigh JH, Taljaard M. Interventions to improve hand hygiene compliance in patient care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 2017(9): CD005186. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005186.pub4 |

| 45. | WHO hand hygiene and antibiotic resistance information for patients and consumers. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/integrated-health-services-(ihs)/clean-hands-2014/patient-tips.pdf?sfvrsn=2710ca60_3 [cited 24 March 2022]. |

| 46. | Doherty C, Stavropoulou C. Patients’ willingness and ability to participate actively in the reduction of clinical errors: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med 2012; 75(2): 257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.056 |

| 47. | World Health Organisation. Patient engagement. 2016. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/252269/9789241511629-eng.pdf [cited 12 April 2023]. |

| 48. | Kingston L, O’connell NH, Dunne CP. Hand hygiene-related clinical trials reported since 2010: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2016; 92(4): 309–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2015.11.012 |

| 49. | Health Protection Surveillance Centre, Government of Ireland. National hand hygiene compliance results. 2020. Available from: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/microbiologyantimicrobialresistance/europeansurveillanceofantimicrobialconsumptionesac/PublicMicroB/HHA/Report1.html [cited 9 December 2020]. |

| 50. | Erasmus V, Daha TJ, Brug H, Richardus JH, Behrendt MD, Vos MC, et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Ctrl Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31(3): 283–94. doi: 10.1086/650451 |

| 51. | Brühwasser C, Hinterberger G, Mutschlechner W, Kaltseis J, Lass-Flörl C, Mayr A. A point prevalence survey on hand hygiene, with a special focus on Candida species. Am J Infect Ctrl 2016; 44(1): 71–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.07.033 |

| 52. | Tan AK, Jr, Jeffrey Olivo BS. Assessing healthcare associated infections and hand hygiene perceptions amongst healthcare professionals. Int J Caring Sci 2015; 8(1): 108. |

| 53. | Thorne S. Interpretive description. eBook edition. Routledge, New York; 2016. doi: 10.4324/9781315426259 |

| 54. | Hunt MR. Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Qual Health Res 2009; 19(9): 1284–92. doi: 10.1177/1049732309344612 |

| 55. | O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89(9): 1245–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 |

| 56. | Tongco MD. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobot Res Appl 2007; 5: 147–58. doi: 10.17348/era.5.0.147-158 |

| 57. | Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. Kindle edition. SAGE Publications, London; 2022. |

| 58. | DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health 2019; 7(2): e000057. doi: 10.1136/fmch-2018-000057 |

| 59. | Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018; 52(4): 1893–907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 |

| 60. | Alzyood M, Jackson D, Brooke J, Aveyard H. An integrative review exploring the perceptions of patients and healthcare professionals towards patient involvement in promoting hand hygiene compliance in the hospital setting. J Clin Nurs 2018; 27(7–8): 1329–45. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14305 |

| 61. | Wu KS, Lee SS, Chen JK, Tsai HC, Li CH, Chao HL, et al. Hand hygiene among patients: attitudes, perceptions, and willingness to participate. Am J Infect Ctrl 2013; 41(4): 327–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.03.033 |

| 62. | Agreli HF, Murphy M, Creedon S, Bhuachalla CN, O’Brien D, Gould D, et al. Patient involvement in the implementation of infection prevention and control guidelines and associated interventions: a scoping review. BMJ Open 2019; 9(3): e025824. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025824 |

| 63. | Davis R, Parand A, Pinto A, Buetow S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of strategies to encourage patients to remind healthcare professionals about their hand hygiene. J Hosp Infect 2015; 89(3): 141–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.11.010 |

| 64. | IPAC Q. Engaging patients as observers in monitoring hand hygiene compliance in ambulatory care. Can J Infect Ctrl 2017; 32(3): 150–3. |

Appendix 1. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)

Paper title

Patients beliefs attitudes and experiences of hand hygiene in a primary care centre.

| Title and abstract | Sentence or section within paper |

| Title – Concise description of the nature and topic of the study; identifying the study as qualitative or indicating the approach (e.g. ethnography and grounded theory) or data collection methods (e.g. interview and focus group) is recommended | Patient’s beliefs attitudes and experiences of hand hygiene in a primary care centre. |

| Abstract – Summary of key elements of the study using the abstract format of the intended publication; typically includes background, purpose, methods, results and conclusions | Title Page |

| Introduction | Sentence or section within paper |

| Problem formulation – Description and significance of the problem/phenomenon studied; review of relevant theory and empirical work; problem statement | Background |

| Purpose or research question – Purpose of the study and specific objectives or questions | There is extensive research on healthcare workers’ relationship with hand hygiene and the moments of hand hygiene. Very little evidence exists regarding patients’ hand hygiene experiences using health care in the community. |

| Methods | Sentence or section within paper |

| Qualitative approach and research paradigm – Qualitative approach (e.g. ethnography, grounded theory, case study, phenomenology and narrative research) and guiding theory if appropriate; identifying the research paradigm (e.g. postpositivist and constructivist/interpretivist) is also recommended; rationale** |

|

| Researcher characteristics and reflexivity – Researchers’ characteristics that may influence the research, including personal attributes, qualifications/experience, relationship with participants, assumptions and/or presuppositions; potential or actual interaction between researchers’ characteristics and the research questions, approach, methods, results and/or transferability | All interviews were conducted and audio-recorded by Anne-Marie Kinsella (AMK) who has a professional interest in IPC and hand hygiene experiences in the community. Reflexivity exercises were carried out throughout. |

| Context – Setting/site and salient contextual factors; rationale** | The study took place in a primary care centre in Ireland. |

| Sampling strategy – How and why research participants, documents or events were selected; criteria for deciding when no further sampling was necessary (e.g. sampling saturation); rationale** |

|

| Ethical issues pertaining to human subjects – Documentation of approval by an appropriate ethics review board and participant consent, or explanation for lack thereof; other confidentiality and data security issues | Ethical considerations |

| Data collection methods – Types of data collected; details of data collection procedures including (as appropriate) start and stop dates of data collection and analysis, iterative process, triangulation of sources/methods and modification of procedures in response to evolving study findings; rationale** | Data collection |

| Data collection instruments and technologies – Description of instruments (e.g. interview guides and questionnaires) and devices (e.g. audio recorders) used for data collection; if/how the instrument(s) changed over the course of the study |

|

| Units of study – Number and relevant characteristics of participants, documents or events included in the study; level of participation (could be reported in results) | Data analysis |

| Data processing – Methods for processing data prior to and during analysis, including transcription, data entry, data management and security, verification of data integrity, data coding and anonymisation/de-identification of excerpts |

|

| Data analysis – Process by which inferences, themes, etc., were identified and developed, including the researchers involved in data analysis; usually references a specific paradigm or approach; rationale** | Data analysis |

| Techniques to enhance trustworthiness – Techniques to enhance trustworthiness and credibility of data analysis (e.g. member checking, audit trail and triangulation); rationale** | Data analysis |

| **The rationale should briefly discuss the justification for choosing that theory, approach, method, or technique rather than other options available, the assumptions and limitations implicit in those choices, and how those choices influence study conclusions and transferability. As appropriate, the rationale for several items might be discussed together. | |

| Results/findings | Sentence or section within paper |

| Conflicts of interest – Potential sources of influence or perceived influence on study conduct and conclusions; how these were managed | After discussion |

| Funding – Sources of funding and other support; role of funders in data collection, interpretation and reporting | After discussion |

| Discussion | |

| Integration with prior work, implications, transferability and contribution(s) to the field – Short summary of main findings; explanation of how findings and conclusions connect to, support, elaborate on or challenge conclusions of earlier scholarship; discussion of scope of application/generalisability; identification of unique contribution(s) to scholarship in a discipline or field | Discussion |

| Limitations – Trustworthiness and limitations of findings | Discussion |

| Results/findings | Sentence or section within paper |

| Synthesis and interpretation – Main findings (e.g. interpretations, inferences and themes) might include development of a theory or model, or integration with prior research or theory | Results |

| Links to empirical data – Evidence (e.g. quotes, field notes, text excerpts and photographs) to substantiate analytic findings | Results |

| IPC: Infection prevention and control. | |

Appendix 2. Interview guide

| Topic | Guiding questions | Possible follow-up questions |

| General hand hygiene | When you hear hand hygiene what do you think ok? Tell me about your experience of hand hygiene in primary care. |

Is there anything that surprised you? Why do you think it is important for your HCW to wash their hands? How do you think you acquire an infection? Where would you acquire an infection? |

| Moments of hand hygiene | What are your thoughts about the five moments of hand hygiene? | Had you heard of them before now? Do you feel this is something you should know more about, in relation to your episode of care? |

| Glove wearing | What are your thoughts about gloves being worn whilst you are being treated? | Is there more or less of an infection risk whilst wearing them? |

| Role of the patient | It would be good to know if you feel patients have a role in ensuring correct hand hygiene has been performed during the episode of care. | How would you feel asking a staff member to perform hand hygiene? Is this something you have had to do? If yes, what was that like for you? What was the HCWs response? Have you been encouraged to remind your HCW to perform hand hygiene? What practical situations would prompt you? |

| HCW: healthcare worker. | ||