ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Burden of central-line-associated bloodstream infections in 106 Ministry of Health hospitals of Saudi Arabia: a 2-year surveillance study

Khalid H. Alanazi1, Mohammed Alqahtani1, Tabish Humayun1*, Adel Alanazi1, Yvonne S. Aldecoa1, Nasser Alshanbari1, Aiman El-Saed2 and Ghada Bin Saleh1

1Surveillance Department, General Directorate of Infection Prevention and Control (GDIPC), Ministry of Health (MOH), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 2King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Abstract

Background: Although the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) is managing the majority of inpatient bed capacity in Saudi Arabia, surveillance data for central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSI) have never been reported at a national level.

Objectives: To estimate unit-specific CLABSI rates along with central line utilization ratios in MOH hospitals. Additionally, to benchmark such rates and ratios with recognized regional and international benchmarks.

Methods: A prospective surveillance study was conducted in 106 MOH hospitals between January 2018 and December 2019. The data from 14 different types of intensive care units (ICUs) were entered into the Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN) program. The surveillance methodology was similar to the methods of the US National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Center for Infection Control.

Results: During the 2 years of surveillance in ICU setting covering 1,475,177 patient-days and 475,913 central line-days, a total of 1,542 CLABSI events were identified. The overall CLABSI rate was 3.24 (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.08–3.40) per 1,000 central line-days, and the overall central line utilization ratio was 0.32 (95% CI, 0.322–0.323). CLABSI-standardized infection ratios in HESN hospitals were very similar (1.01) to GCC hospitals, but 3.2 times higher than NHSN hospitals and 36% lower than International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) hospitals. Central-line-standardized utilization ratio in MOH hospitals was 15–30% lower than the three benchmarks.

Conclusions: The overall CLABSI rate was 3.24 per 1,000 central line-days, and the overall central line utilization ratio was 0.32. MOH CLABSI rates were very similar to GCC hospitals, but higher than NHSN hospitals and lower than INICC hospitals. MOH central line utilization is slightly lower than the three benchmarks.

Keywords: bloodstream infection; central venous catheter; health care-associated infections; infection control; benchmarking; surveillance; Saudi Arabia

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2021, 17: 20978 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v17.20978

Copyright: © 2021 Khalid H. Alanazi et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 25 October 2020; Revised: 18 May 2021: Accepted: 27 June 2021: Published: 2 September 2021

Competing interests and funding: The authors report no conflicts of interest and funding in this work.

*Tabish Humayun, General Directorate of Infection Prevention and Control, Ministry of Health, PO Box: 11176, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Email: drtabish.ipc.micro.ph@gmail.com

Approximately 5–10% of hospitalized patients acquire health care-associated infections (HAIs) during their hospital stay; 10% of these infections are bloodstream infections (BSIs) (1, 2). Central-line-associated BSI (CLABSI) is one of the most potentially preventable HAIs, with up to 70% preventable with the current evidence-based strategies (3, 4). Nevertheless, CLABSI is still one of the risky HAIs, with substantial morbidity, mortality, excess length of stay, and increased health care costs in different populations (5, 6). Although CLABSI occurs at a relatively lower rate compared with other device-associated HAIs (7, 8), it has been one of the early suggested reportable indicators for HAI risk and health care performance (9).

Routine surveillance is critical to provide information required to improve patient safety and quality of health care services (10). Conducting HAI surveillance and providing timely feedback of infection rates and related process measures to health care providers and other stakeholders are critical steps in the improvement process (11). Additionally, surveillance alone without interventions may induce significant changes in practices and behaviors of health care providers that can be translated into reduced infection rates including CLABSI (12, 13).

Data estimating the burden of CLABSI in Saudi hospitals were limited to sparse reports including a limited number of secondary or tertiary care hospitals (14–16). Although the Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH) is managing close to 60% of the inpatient bed capacity in Saudi Arabia (17), surveillance data for CLABSI have never been reported at a national level. Recently, the availability of the Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN) has enabled the unified collection of CLABSI data from a large number of MOH hospitals. Hospitals with at least 100 beds, an intensive care unit (ICU), a microbiology laboratory, and a full-time microbiologist were included in the study. The data are entered in electronic system by infection control practitioners (ICPs) at the hospital, followed by regional coordinators and supervised by the Office of General Directorate of Infection Prevention and Control (GDIPC). The objective of the current study was to estimate unit-specific CLABSI rates along with central line utilization ratios in MOH hospitals contributing data to the HESN. Additionally, we wanted to benchmark such rates and ratios with recognized regional and international benchmarks.

Methods

Setting

The total number of hospitals in Saudi Arabia at the start of the study was 484, with a total bed capacity of approximately 75,000. Out of them, the MOH was officially funding and supervising 284 hospitals with a total bed capacity of around 43,000. The rate of hospital beds in Saudi Arabia was 22.5 per 10,000 population during 2018. The current study was conducted at 106 MOH hospitals located in 20 different geographic regions across Saudi Arabia. Out of the 106 hospitals, 84.0% were general or central hospitals, 11.3% were maternal and children’s hospitals, and 4.7% were cardiac hospitals (Table 1). The included hospitals have a total of 26,399 beds, including 3,560 ICU beds (Table 1).

Design

A prospective surveillance study was conducted between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2019 using the HESN program.

Population

All MOH hospitals with at least a 100-bed capacity, one ICU, a microbiology laboratory, and a full-time microbiologist were included in the first phase study. Other non-MOH hospitals and private hospitals will be included in the second phase. The data were obtained from 14 different types of ICUs (Table 2). The data were included in the analysis if at least 50 central line days of surveillance were reported per reporting year, 2018 and/or 2019.

| Type of ICU | Number of ICUs* | Central line days | CLABSI events | Mean CLABSI rate | 95% confidence interval | Percentile** | ||||

| 10% | 25% | 50% (median) | 75% | 90% | ||||||

| Burn | 8 | 2,047 | 8 | 3.91 | 1.20–6.62 | |||||

| Medical | 35 | 43,168 | 148 | 3.43 | 2.88–3.98 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.10 | 7.08 | 9.54 |

| Medical cardiac | 27 | 12,335 | 28 | 2.27 | 1.43–3.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.10 | 6.00 |

| Medical surgical | 147 | 247,539 | 566 | 2.29 | 2.10–2.47 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.63 | 3.70 | 5.96 |

| Neurosurgical | 3 | 3,574 | 3 | 0.84 | 0.00–1.79 | |||||

| Neonatal | 88 | 120,734 | 673 | 5.57 | 0.00–6.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.88 | 7.01 | 10.37 |

| Pediatric cardiothoracic | 2 | 828 | 2 | 2.42 | 0.00–5.76 | |||||

| Pediatric medical | 12 | 6,317 | 46 | 7.28 | 5.18–9.39 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 8.23 | 14.41 |

| Pediatric medical surgical | 28 | 24,129 | 59 | 2.45 | 1.82–3.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.08 | 7.83 | 12.74 |

| Pediatric surgical | 2 | 427 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | |||||

| Respiratory | 1 | 1,557 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | |||||

| Surgical | 6 | 6,845 | 1 | 0.15 | 0.00–0.43 | |||||

| Surgical cardiothoracic | 5 | 3,556 | 4 | 1.12 | 0.02–2.23 | |||||

| Trauma | 3 | 2,857 | 4 | 1.40 | 0.03–2.77 | |||||

| Total | 367 | 475,913 | 1,542 | 3.24 | 3.08–3.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.83 | 4.96 | 7.95 |

*ICUs contributing less than 50 central line days per year were excluded from the analysis. **Standard percentiles were calculated only when at least 20 hospitals were contributing data for a specific type of ICU. |

||||||||||

Definitions

CLABSI was defined as a laboratory-confirmed primary BSI that was not secondary to another infection or alternative etiology (18, 19). The patient should have a central line or umbilical catheter for more than 2 calendar days, which was in place at or within 2 calendar days before the date of CLABSI. The blood culture should grow a recognized pathogen in one or more blood specimens or a common skin contaminant in two or more blood specimens in the presence of infection symptoms. These include fever, chills, or hypotension in any patient or fever, hypothermia, apnea, or bradycardia in neonatal patients.

Surveillance strategy

The surveillance strategy was similar to the one suggested by the US National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) (18) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Center for Infection Control (19). The surveillance was active, patient-based, and prospective targeted, which was done in specific ICUs for specific durations after a local infection risk assessment.

HESN program

The HESN is an integrated national Health Electronic Surveillance Network that has several domains to uniformly monitor communicable diseases, disease epidemics, immunization, and HAIs across Saudi Arabia (20). It allows users at different hospitals to continually and uniformly report HAIs to the GDIPC at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. CLABSI and central line use data were collected and entered in the electronic system after identifying the CLABSIs based on the definitions, by ICPs at their respective hospitals. Infection control professionals were informed by the laboratory about any positive blood cultures in the ICUs and follow these cases in the respective ICUs. The data were directly entered into the HESN program at two levels: central line form and CLABSI event form.

The number of central line days was counted daily at a fixed time (usually in the morning around 8:00 or 10:00 AM), for all patients with a central line. A difference of ±5% of the manually collected daily count and electronic count was acceptable for validation purposes, to avoid the possibility of human error.

The surveillance department of GDIPC at MOH provided the included hospitals with the required training in surveillance definitions, surveillance methodology, use of the HESN program, and information technology support. Training workshops for the ICPs and regional coordinators, followed by hands on training, were conducted in all regions (during 2017) before the start of the study.

ICUs contributing less than 50 central line days per year and birth weight categories with less than 50 central line days per year were excluded from the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data from all regions were extracted from HESN program and analyzed using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data extraction, management, analysis, and interpretations were done centrally at the GDIPC. CLABSI rates (expressed per 1,000 central line days) and central line utilization ratios were calculated and stratified by the type of ICU and additionally by the birth weight groups in neonatal ICU (6, 14). Confidence intervals (CIs) (14) and standard percentiles (6) were calculated for both CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios. Percentiles were not calculated for ICU types with less than 20 data points (per hospital year of surveillance). To benchmark current CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios with international benchmarks, standardized infection ratio (SIR) and standardized utilization ratio (SUR) were calculated, respectively, after adjusting for differences in ICU types (all ICUs) and birth weight groups (neonatal ICUs). SIR and SUR were calculated by dividing the number of observed CLABSI events and central line days, respectively, by their expected values (18). The expected values were calculated using the published reports of NHSN (6), GCC (14), and International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) (5). P-values were two tailed. A P-value of <0.05 was considered as significant.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, KSA (IRB log number: 20-011E, January 2020).

Results

During the 2 years of surveillance covering 1,475,177 patient-days and 475,913 central line-days, a total of 1,542 CLABSI events were identified. As shown in Table 2, the overall CLABSI rate was 3.24 per 1,000 central line-days with 95% CI between 3.08 and 3.40. The 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles were 1.83, 4.96, and 7.95, respectively. Five types of ICUs contributed more than 90% of the central line-days reported by all types of ICUs: medical surgical, neonatal, medical, pediatric medical surgical, and medical cardiac. CLABSI rates per 1,000 central line-days were highest in pediatric medical (7.28), neonatal (5.57), burn (3.91), and medical ICUs (3.43), but lowest in pediatric surgical (0.0), respiratory (0.0), and surgical ICUs (0.15).

As shown in Table 3, the overall central line utilization ratio was 0.32, with 95% CI between 0.322 and 0.323. The 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles were 0.29, 0.49, and 0.62, respectively. The central line utilization ratios were highest in respiratory (0.54), pediatric cardiothoracic (0.53), and surgical cardiothoracic ICUs (0.53), but lowest in burn (0.13), medical cardiac (0.19), and pediatric surgical ICUs (0.21).

| Type of ICU | Number of ICUs* | Patient days | Central line days | Utilization ratio | 95% confidence interval | Percentile** | ||||

| 10% | 25% | 50% (median) | 75% | 90% | ||||||

| Burn | 8 | 15,945 | 2,047 | 0.13 | 0.123–0.134 | |||||

| Medical | 35 | 98,595 | 43,168 | 0.44 | 0.435–0.441 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.76 |

| Medical cardiac | 27 | 63,691 | 12,335 | 0.19 | 0.191–0.197 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.63 |

| Medical surgical | 147 | 574,323 | 247,539 | 0.43 | 0.430–0.432 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.64 |

| Neurosurgical | 3 | 7,741 | 3,574 | 0.46 | 0.451–0.473 | |||||

| Neonatal | 88 | 556,820 | 120,734 | 0.22 | 0.216–0.218 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.50 |

| Pediatric cardiothoracic | 2 | 1,552 | 828 | 0.53 | 0.509–0.558 | |||||

| Pediatric medical | 12 | 29,078 | 6,317 | 0.22 | 0.213–0.222 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.51 |

| Pediatric medical surgical | 28 | 94,613 | 24,129 | 0.26 | 0.252–0.258 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.20 | 0.35 | 0.53 |

| Pediatric surgical | 2 | 2,048 | 427 | 0.21 | 0.191–0.226 | |||||

| Respiratory | 1 | 2,896 | 1,557 | 0.54 | 0.519–0.556 | |||||

| Surgical | 6 | 15,157 | 6,845 | 0.45 | 0.444–0.460 | |||||

| Surgical cardiothoracic | 5 | 6,754 | 3,556 | 0.53 | 0.515–0.538 | |||||

| Trauma | 3 | 5,964 | 2,857 | 0.48 | 0.466–0.492 | |||||

| Total | 367 | 1,475,177 | 475,913 | 0.32 | 0.322–0.323 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 0.62 |

*ICUs contributing less than 50 central line days per year were excluded from the analysis. **Standard percentiles were calculated only when at least 20 hospitals were contributing data for a specific type of ICU. |

||||||||||

CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios stratified by birth-weight groups in neonatal ICUs are shown in Table 4. The overall CLABSI rate was 5.57 per 1,000 central line-days, and the central line utilization ratio was 0.22. CLABSI rates per 1,000 central line-days decreased as birth weight group increased: 7.15 in neonates ≤750 g and 4.67 in neonates >2,500 g. On the other hand, central line utilization ratios generally increased as birth weight group increased: 0.19 in neonates ≤750 g and 0.28 in neonates >2,500 g.

| Birth weight category | Number of ICUs* | Patient days | Central line days | CLABSI events | Mean CLABSI rate | 95% confidence interval | Utilization ratio | 95% confidence interval |

| ≤750 g | 79 | 70,786 | 13,388 | 96 | 7.15 | 5.72–8.58 | 0.19 | 0.186–0.192 |

| 751–1,000 g | 76 | 131,831 | 24,387 | 162 | 6.65 | 5.63–7.67 | 0.18 | 0.183–0.187 |

| 1,001–1,500 g | 88 | 158,839 | 31,714 | 169 | 5.34 | 4.53–6.14 | 0.20 | 0.198–0.202 |

| 1,501–2,500 g | 88 | 105,969 | 26,639 | 131 | 4.92 | 4.07–5.76 | 0.25 | 0.249–0.254 |

| >2,500 g | 88 | 89,395 | 24,605 | 115 | 4.67 | 3.81–5.52 | 0.28 | 0.272–0.278 |

| Total | 88 | 556,820 | 120,734 | 673 | 5.57 | 5.15–6.00 | 0.22 | 0.216–0.218 |

| *Birth weight category with less than 50 central line days per year were excluded from the analysis. | ||||||||

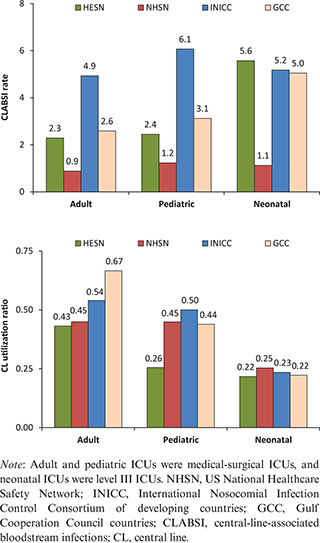

Figure 1 compares CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios in adult, pediatric, and neonatal ICUs in MOH hospitals with other recognized benchmarking networks. CLABSI rates in adult and pediatric medical-surgical ICUs in HESN were higher than NHSN rates, lower than INICC rates, and very close to GCC rates. CLABSI rates in neonatal ICUs in HESN were fivefold higher than NHSN rates and slightly higher than INICC and GCC rates. Central line utilization ratios in adult medical-surgical ICUs in HESN were similar to NHSN but lower than INICC and GCC. Central line utilization ratios in HESN were lower than the three benchmarks in pediatric medical-surgical ICUs and similar to the three benchmarks in neonatal ICUs.

Fig. 1. Comparisons of CLABSI rates per 1,000 central line days (above) and central line utilization ratios (below) between Saudi Health Electronic Surveillance Network (HESN) and other recognized benchmarking networks by the type of intensive care unit (adult, pediatric, and neonatal).

Table 5 compares CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios in MOH hospitals with the three benchmarks using SIR and SUR, respectively. CLABSI SIR (Standardized Infection Ratios) across all types of ICUs in MOH hospitals were very similar (1.01) to GCC hospitals, but threefold higher (3.23) than NHSN hospitals and one-third (0.64) lower than INICC hospitals. Central line SUR (Standardized Utilization Ratios) across all types of ICUs in HESN hospitals were 15–30% lower than the three benchmarks.

Table 6 compares CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios in neonatal ICUs in MOH hospitals with the three benchmarks using SIR and SUR, respectively. CLABSI SIR across all birth weight groups in neonatal ICUs in MOH hospitals were very similar (1.08) to INICC hospitals and slightly higher (1.15) than GCC hospitals, but 5.7-fold higher than NHSN hospitals. Central line SUR ratios across all birth weight groups in neonatal ICUs in HESN hospitals were 12–22% lower than the three benchmarks.

Discussion

We are reporting the CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios in more than 100 MOH hospitals. This study is by far the largest CLABSI surveillance study conducted among Saudi Arabia and other GCC countries (14, 15, 21). The number of hospitals included in this study represents approximately 37% of all MOH hospitals and 22% of all Saudi hospitals. This large number of hospitals enables the current report to perfectly serve as a national and probably Saudi CLABSI benchmark. To serve the benchmarking purpose, CIs and standard percentiles have been created for both rates and ratios. Additionally, rates and ratios were presented separately for 14 different types of ICUs. Finally, calculating SIRs and SURs compared with recognized regional and international benchmarks gives better interpretation of local CLABSI data. Creating a nationally representative benchmark is a critical step in pushing HAI preventive practices and creating a culture of competitiveness between hospitals (22).

The overall MOH CLABSI rate was 3.24 per 1,000 central line-days. This rate is very similar to the rate reported by GCC (3.1 per 1,000 central line-days), which included data from four National Guard hospitals in Saudi Arabia and two hospitals from Oman and Bahrain between 2008 and 2013 (14). Additionally, the current MOH rate is considered in the lower side of highly variable CLABSI rates in different local multihospital studies that used similar surveillance methodology (15, 16). For example, CLABSI rates ranged between 2.2 and 10.5 per 1,000 central line-days in 12 medical-surgical ICUs in Saudi Arabia (15). Additionally, interventional studies reported CLABSI rates ranging between 6.9 and 10.1 per 1,000 central line-days before preventive interventions and 0.0 and 6.5 per 1,000 central line-days after preventive interventions in multiple- (16) and single-hospital studies (21, 23, 24).

The overall MOH central line utilization ratio was generally lower than the majority of previous surveillance studies in Saudi Arabia. It was 0.32 in the current study compared with 0.45 in the GCC report (14), 0.52 in a multihospital study (15), 0.59–0.61 in a tertiary-care hospital in the Eastern region (21), and 0.51–087 in a tertiary-care hospital in Jeddah (24). The lower central line utilization in the current study may be reflecting the generally lower MOH CLABSI rates. Additionally, one-third of the MOH data were derived from pediatric and neonatal populations, which are traditionally associated with lower central line utilization than adult populations (0.22 vs. 0.41 in the current study), while the majority of the previous data were derived from adult ICUs (15, 21, 24). Finally, the majority of MOH hospitals were general hospitals, while several previous studies were tertiary-care hospitals, which are traditionally associated with higher central line utilization (14, 21, 24).

Comparing MOH unit-specific CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios with previous local studies is very challenging. While the current study included 14 types of ICUs (nine adult, four pediatric, and one neonatal ICU), most of the previous studies include one to a maximum of three types of ICU with the data largely derived from medical-surgical ICUs (15, 21, 24). Even the only study that focused on different types of ICUs had 95% of the data derived from three ICUs (14). Moreover, previously reported CLABSI rates and central line utilization in pediatric and neonatal ICUs were either relatively old (25, 26) or never separated from the whole analysis (16, 27).

The MOH CLABSI SIRs across all types of ICUs were very similar to GCC hospitals, but higher than NHSN hospitals and lower than INICC hospitals. Similarly, the GCC study reported that the risk of CLABSI in GCC hospitals was approximately 150% higher than NHSN hospitals and 33% lower than INICC hospitals (14). The differences between the three hospital groups, the effectiveness of the infection control programs, and HAI surveillance may be related to training, resources, and regulations, which are clearly favorable in US hospitals than hospitals in developing countries. This finding underscores the potential for the improvement in CLABSI rates in Saudi hospitals, if appropriate preventive practices are strictly implemented. Consistently, the similarity between the findings in the MOH and GCC studies is not surprising, given the similar infection control practices in the region. Interestingly, the MOH SURs across all ICUs including neonatal ICUs indicate that the central line utilization is probably optimal, which may be reflecting the implementation of central line bundle in all included hospitals.

In short, we are reporting the CLABSI rates and central line utilization ratios in more than 100 MOH hospitals. The overall CLABSI rate was 3.24 per 1,000 central line-days, and the overall central line utilization ratio was 0.32. MOH CLABSI rates were very similar to GCC hospitals, but higher than NHSN hospitals and lower than INICC hospitals. MOH central line utilization is slightly lower than the three benchmarks. The current MOH rates and ratios can be perfectly used as a national Saudi CLABSI benchmark. This is an important step in pushing HAI preventive practices forward and creating a culture of competitiveness between hospitals in the region.

In spite of improvement, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is still facing certain challenges, such as overcrowding, a high number of gram-negative bacteria, scarcity of local and international guidelines, and the limited number of experienced and certified infection control and epidemiological staff, which contribute to a high number of HAIs. Challenges to further improving surveillance in MOH hospitals include data validation, site audits, and rapid turnover of ICPs.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the General Directorate of Infection Prevention and Control (GDIPC), ICPs, Regional Coordinators, and the HESN Team at MOH, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have been acknowledged as contributors of submitted work and fulfill the standard criteria for authorship. All authors have read and approved the submission of the current version of the manuscript. The material included in this manuscript is original, and it has been neither published elsewhere nor submitted for publication simultaneously.

References

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Point prevalence survey of healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial use in European hospitals 2011–2012. 2013. Available from: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/media/en/publications/Publications/healthcare-associated-infections-antimicrobial-use-PPS.pdf [cited 1 September 2020].

- Alshamrani MM, El-Saed A, Alsaedi A, El Gammal A, Al Nasser W, Nazeer S, et al. Burden of healthcare-associated infections at six tertiary-care hospitals in Saudi Arabia: a point prevalence survey. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2019; 40(3): 355–7. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.338

- Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Doshi JA, Agarwal R, Williams K, Brennan PJ. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32(2): 101–14. doi: 10.1086/657912

- Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Rodrigues C, Alvarez-Moreno C, Leblebicioglu H, Sobreyra-Oropeza M, et al. Impact of International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) strategy on central line-associated bloodstream infection rates in the intensive care units of 15 developing countries. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31(12): 1264–72. doi: 10.1086/657140

- Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Mehta Y, Leblebicioglu H, Memish ZA, Al-Mousa HH, et al: International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortiu (INICC) report, data summary of 43 countries for 2007–2012. Device-associated module. Am J Infect Control 2014; 42(9): 942–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.05.029

- Dudeck MA, Edwards JR, Allen-Bridson K, Gross C, Malpiedi PJ, Peterson KD, et al. National Healthcare Safety Network report, data summary for 2013, Device-associated Module. Am J Infect Control 2015; 43(3): 206–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.11.014

- World Health Organization. Report on the burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. A systematic review of the literature. 2011. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241501507_eng.pdf [cited 1 February 2015].

- Han Z, Liang SY, Marschall J. Current strategies for the prevention and management of central line-associated bloodstream infections. Infect Drug Resist 2010; 3: 147–63. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S10105

- McKibben L, Horan T, Tokars JI, Fowler G, Cardo DM, Pearson ML, et al. Guidance on public reporting of healthcare-associated infections: recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control 2005; 33(4): 217–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.04.001

- Ling ML, Apisarnthanarak A, Jaggi N, Harrington G, Morikane K, Thu le TA, et al. APSIC guide for prevention of Central Line Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI). Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2016; 5: 16. doi: 10.1186/s13756-016-0116-5

- van Mourik MSM, Perencevich EN, Gastmeier P, Bonten MJM. Designing surveillance of healthcare-associated infections in the era of automation and reporting mandates. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(6): 970–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix835

- Gastmeier P, Geffers C, Brandt C, Zuschneid I, Sohr D, Schwab F, et al. Effectiveness of a nationwide nosocomial infection surveillance system for reducing nosocomial infections. J Hosp Infect 2006; 64(1): 16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.04.017

- Chen LF, Vander Weg MW, Hofmann DA, Reisinger HS. The Hawthorne Effect in infection prevention and epidemiology. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36(12): 1444–50. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.216

- Balkhy HH, El-Saed A, Al-Abri SS, Alsalman J, Alansari H, Al Maskari Z, et al. Rates of central line-associated bloodstream infection in tertiary care hospitals in 3 Arabian gulf countries: 6-year surveillance study. Am J Infect Control 2017; 45(5): e49–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.01.027

- Gaid E, Assiri A, McNabb S, Banjar W. Device-associated nosocomial infection in general hospitals, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013–2016. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2018; 7 Suppl 1: S35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2017.10.008

- Al-Abdely HM, Alshehri AD, Rosenthal VD, Mohammed YK, Banjar W, Orellano PW, et al. Prospective multicentre study in intensive care units in five cities from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: impact of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) multidimensional approach on rates of central line-associated bloodstream infection. J Infect Prev 2017; 18(1): 25–34. doi: 10.1177/1757177416669424

- Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH). Statistical Yearbook 1439H (2018 G). 2019. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/book-Statistics.pdf [cited 1 September 2020].

- National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). NHSN patient safety component manual. Januray 2018. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/PDFs/pscManual/pcsManual_current.pdf [cited 1 September 2020].

- GCC Centre for Infection Control and Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs. Healthcare-associated Infections surveillance manual, 3rd edition. 2018. Available from: http://ngha.med.sa/English/MedicalCities/AlRiyadh/MedicalServices/Documents/3rd_edition_Surveillance_Manual.pdf [cited 1 September 2020].

- Saudi Ministry of Health (MOH). Health Electronic Surveillance Network. 2020. Available from: https://hesn.moh.gov.sa/webportal/ [cited 1 September 2020].

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Amalraj A, Memish ZA. Reduction and surveillance of device-associated infections in adult intensive care units at a Saudi Arabian hospital, 2004–2011. Int J Infect Dis 2013; 17(12): e1207–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.06.015

- El-Saed A, Balkhy HH, Weber DJ. Benchmarking local healthcare-associated infections: available benchmarks and interpretation challenges. J Infect Public Health 2013; 6(5): 323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.05.001

- Bukhari S, Banjar A, Baghdadi S, Baltow B, Ashshi A, Hussain W. Central line associated blood stream infection rate after intervention and comparing outcome with national healthcare safety network and international nosocomial infection control consortium data. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2014; 4(5): 682–6. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.141499

- Khalid I, Al Salmi H, Qushmaq I, Al Hroub M, Kadri M, Qabajah MR. Itemizing the bundle: achieving and maintaining ‘zero’ central line-associated bloodstream infection for over a year in a tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control 2013; 41(12): 1209–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2013.05.028

- Almuneef MA, Memish ZA, Balkhy HH, Hijazi O, Cunningham G, Francis C. Rate, risk factors and outcomes of catheter-related bloodstream infection in a paediatric intensive care unit in Saudi Arabia. J Hosp Infect 2006; 62(2): 207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.06.032

- Balkhy HH, Alsaif S, El-Saed A, Khawajah M, Dichinee R, Memish ZA. Neonatal rates and risk factors of device-associated bloodstream infection in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control 2010; 38(2): 159–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.004

- Khan M. Surveillance of device associated infections in critical care areas. Int J Pathol 2014; 12(12): 63–8.