PRACTICE FORUM

The successful development and implementation of an off campus triage system during the COVID-19 pandemic in Guangdong, China

Ri-hua Xie1,2, Yanfang Chen1, Ziyu Xiong1, Jie Wang1, Lepeng Zhou1, Ning Li2,3, Smita Pakhale4,5,6, D. William Cameron5,6,8, Daniel Krewski6,7 Shi Wu Wen5,6,8*

1Department of Nursing, The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Foshan, Guangdong, China; 2General Practice Center, The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Foshan, Guangdong, China; 3Department of Pediatric, The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, Foshan, Guangdong, China; 4Division of Respiratory, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 5Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 6School of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 7McLaughlin Centre for Population Health Risk Assessment, University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; 8Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Abstract

To deal with the public health crisis caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, we developed an off campus triage system at entry points to the outpatient, emergency, and inpatient departments. To enhance this off campus triage system, we implemented intensive staff training and made detailed triage plans with a timely referral. Of the 85,414 patients/visitors who visited The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University, one of the government-designated hospitals to triage-suspected COVID-19 patients between January 22 and March 10, 2020, 359 patients were triaged to the COVID-19 fever clinic and 1,218 were triaged to the general fever clinic; 187 were suspected of COVID-19 infection and quarantined; and four cases of COVID-19 were confirmed and referred. During the outbreak, no inhospital infection and no complaint from patients and their family members occurred, and up to September 10, 2020, no new cases of COVID-19 in this hospital or its catchment area were detected. The off campus triage system is an effective approach to improve the detection of COVID-19 infection and reduce inhospital cross infection.

Keywords: COVID-19; off-campus triage system; staff training; infection control; management research

Citation: Int J Infect Control 2021, 17: 20918 – http://dx.doi.org/10.3396/ijic.v17.20918

Copyright: © 2021 Ri-hua Xie et al. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), allowing third parties to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and to remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided the original work is properly cited and states its license.

Received: 10 October 2020; Revised: 11 January 2021; Accepted: 13 January 2021; Published: 30 July 2021

Competing interests and funding: All authors declare the following: no support from any organization for the submitted work, no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years, and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

This study was supported in part by grants from Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FND-148438), Clinical Research Startup Program of Southern Medical University by High-level University Construction Funding of Guangdong Provincial Department of Education (LC2019ZD019), The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University (YNKT201802), Key Project of Nursing Scientific Research Plan of Southern Medical University (Z2019001), and Foshan Special Project of Emergency Science and Technology Response to COVID-19 (2020001000376). However, the funders played no role on data analysis or result interpretation.

*Shi Wu Wen, OMNI Research Group, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Email: swwen@ohri.ca

An unprecedented outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, Hubei, China, emerged in December 2019. A novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, having characteristics typical of coronavirus family and belonging to the betacoronavirus 2B lineage, whose genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 share 79.5% sequence identity to SARS-CoV, was identified as the causative agent and was subsequently termed as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) by the World Health Organization (WHO) (1). Due to lack of immunity, the general population is susceptible to infection with COVID-19, which is spread from person to person by respiratory droplets and contact transmission as important ways of spreading (2, 3). Patients affected by this virus most notably presented with clinical manifestations of dry cough, fever, and bilateral lung infiltrates on imaging (2, 4). A minority of patients were asymptomatic, however (5). The WHO Global Health Emergency Committee has stated that the spread of COVID-19 may be prevented by early effective surveillance, isolation, prompt treatment, and the implementation of a robust system to trace contacts (6).

Hospitals are considered important settings for COVID-19 triage because they also need to treat large numbers of non-COVID-19 patients during the epidemic. Traditional hospital triage models could not handle this large-scale public health crisis, and missteps in the triage process could result in missed cases, inhospital cross infection, and delayed treatment of other critically ill patients. The situation is particularly difficult for hospitals with no separate ambulance/emergency departments for respiratory and non-respiratory health problems. It is, therefore, important to arrange patients’ medical treatment to achieve early screening for and early treatment of COVID-19 cases, as well as to avoid inhospital cross infection, improve patient’s satisfaction, and enhance efficiency of delivery of hospital services.

In January 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak that originated in Wuhan, Hubei, spread to Guangdong, China. Subsequently, Guangdong became the province with the second largest number of COVID-19 patients. The Seventh Affiliated Hospital, one of the main teaching hospitals of Southern Medical University, is a designated hospital for the fever clinic for the COVID-19 outbreak in Foshan, Guangdong.

To deal with this public health crisis and to reduce inhospital cross infection, we developed an off campus triage system at entry points to the outpatient, emergency, and inpatient departments for all patients and visitor, with or without respiratory symptoms. In this article, we describe the creation of the novel off campus in The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University and share the experience that we have gained from the successful development and implementation of this system.

The development and implementation of the off campus triage system

Establishing triage points outside the hospital campus

The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University does not have separate ambulance/emergency departments for respiratory and non-respiratory health problems, making the triage an even more challenging problem during the pandemic. As the first step in responding to the public health crisis caused by the outbreak of COVID-19, we set up tents to establish triage points at the entrance of the outpatient, emergency, and inpatient departments outside the hospital. The creation of external tent-based triage points has played an important role in reducing long lineups and crowding, thereby reducing the chance of inhospital cross infection, as well as relieving anxiety among patients and their families. Setting up different triage points outside the hospital could also meet diverse patient needs and improve the efficiency of hospital services: the emergency triage point, for example, is very convenient for car accidents, and the inpatient triage point is convenient for family members.

The effectiveness of moving triage points outside the hospital campus has been demonstrated in previous public health crises. During the outbreak of Ebola, it was reported that using off campus tents to establish a medical care center to conduct initial assessment and treatment of Ebola patients was an effective way to handle such a crisis (7). An Afghan refugee camp used tents sprayed or impregnated with deltamethrin to prevent malaria (8). Studies have shown that the use of tents, combined with hospital infection management measures, may effectively limit the spread of infectious diseases during infectious disease outbreaks (9, 10).

Staff training, supervising, and scheduling

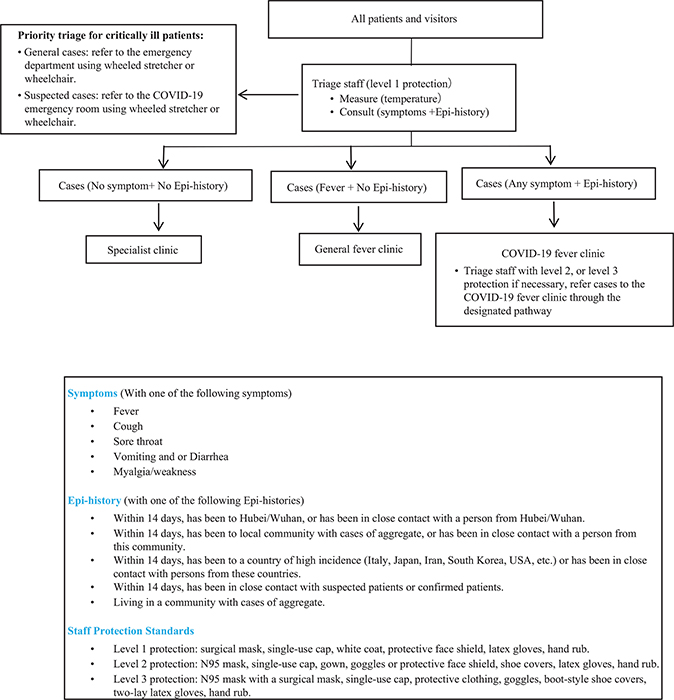

All triage staff were trained to learn and apply triage procedures; appropriate personal protection and protection levels based on all patients’ and visitors’ temperature, symptoms, and epidemiological history (Fig. 1); appropriate use of personal protective equipment; disinfection; and isolation. This was done using both online and offline training materials, including text and videos, administered in the form of both self-learning and guided training modules. The text part consists mainly of guidance documents such as diagnosis and treatment programs, protection and disposal processes, and prevention and control guides, while the videos are mostly operation videos of wearing and taking off isolation clothing and protective clothing, and patient care. Staff were permitted to work at triage points only after an intensive training on personal protection and infection prevention/control, and after a formal assessment and approval by hospital leadership. Head nurses or team leaders inspected triage points on daily basis to ensure that all staff followed the triage procedures and personal protection measures correctly. Studies have shown that staff training during infectious disease outbreaks is essential to improve awareness of self-protection and reduce the risk of infection of medical staff (11–15).

Fig. 1. Coronavirus disease 2019 triage flowchart.

We implemented a 24-h rotational shift system at the emergency triage point. Because of different patient volume at the other two triage points, shift times varied from 7:30 to 17:30 at the outpatient triage point and from 7:30 to 18:00 at the inpatient triage point. To reduce staff needs and the consumption of protective equipment and other materials, we adjusted the number of triage staff deployed on an ongoing basis, depending on the number of hospital visits occurring in different periods. During the outbreak of SARS (CoV-1) and H1N1 influenza, studies have demonstrated that the implementation of a 24-h rotating shift system, the optimization of shift arrangements, and the promotion of quality control awareness among staff supported efficient triage and improved case detection rates (11, 12, 16, 17). Furthermore, the shift schedule form included triage staff contact information and original department in case of emergency management.

Developing the triage flowchart

Based on the ‘Pneumonitis Diagnosis and Treatment Program for New Coronavirus Infection, Guidelines from National and Guangdong Provincial Health Commissions on Further Improving the Prevention of and Control of Infection of Medical Staff’ and other documents from Guangdong government, we formulated and updated the triage flowchart (Fig. 1) to ensure the accuracy and timeliness of information collection and to improve the detection rate. Most inhospital transmission occurred when infection prevention and control precautions were not fully developed or well executed (18–21). Formulation of triage flowcharts and the management of triage are essential to prevent the spread of infections. An emergency department in Toronto developed a detailed triage flowchart during the outbreak of SARS to improve hospital triage efficiency (19). A study on hospital management in Ebola indicated that triage processes should be standardized (22). During the development of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in Qatar, the diagnosis rate was improved by formulating an effective triage process to avoid cross infection (23). During the outbreak of SARS and H1N1 influenza in China, several studies have suggested that formulating clear triage processes and emergency plans could significantly improve efficiency (12, 13, 20).

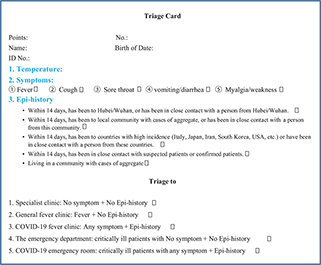

Designing a triage card with personal and epidemiologic information for patients and visitors

We designed a triage card to collect clinical and epidemiologic information for every patient and visitor to the hospital at each of the triage points (Fig. 2). All patients and visitors are required to carry and present this card during their visit to the hospital. If an individual was identified as a suspected COVID-19 patient (Fig. 2), he/she was escorted to the fever clinic by triage staff according to the protection levels specified for the designated pathway.

Fig. 2. Coronavirus disease 2019 triage card.

Registering information of fever patients

According to the national guidelines on the COVID-19 outbreak in China, we developed a registration form to collect data on temperature and symptoms for fever patients and suspected COVID-19 patients at all triage points (Table 1). This registration form is kept at each triage point to facilitate patient tracing and communications between staff at triage and staff at fever clinics. During the outbreak of SARS, hospitals in Toronto implemented an efficient method of registering the patient’s name, home address, and other relevant information to regulate patient management (19). Studies have shown that the use of patient registration can help to improve detection (16, 24).

| No. | Date | Name | Age | Sex | Temp-erature | First visit | Repeat visit | Address | ID No. | Epidemiological History (√) | Symptoms (√) | Clinic site sent (√) | Triage staff signature | |||||||||

| Phone No. | Hubei/Wuhan visit | Community with infection | Close contact with patients | Back from countries with high incidence* | Crowd gathering | Sore throat | Cough | Vomit | Diarrhea | Myalgia/ weakness | General fever clinic | COVID-19 fever clinic | ||||||||||

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| *Countries with high incidence: Italy, Japan, Iran, Korea, German, Spain, and the United States. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Cleaning and disinfection at the triage points

Chlorine-containing disinfectants are used to disinfect electronic and mercury thermometers, work surfaces, wheelchairs, wheeled stretchers, and the general work environment every 4 h. The disinfectant used for wiping and spraying is 2,000 mg/L of hypochlorite solution. Before and after triaging patients, triage staff are required to wash their hands with hand sanitizer and dry hands with paper towel. Each cleaning process was recorded upon completion. Moreover, we followed strict standards in accordance with the regulations and methods for medical waste management in health institutions to dispose medical waste (25).

Patient- and family-friendly triage environment

Patient-friendly measures were implemented to ensure that patients and their families were satisfied with our triage process. We marked the triage points with clear directions, so that patients would have no difficulty in finding their designated triage point. The triage process was explained in detail by staff at all triage points. Staff at the triage points created a patient- and family-friendly environment and paid attention to their personal needs to improve their satisfaction (26, 27). Triage staff used plain language to communicate with patients to help them understand the current issues regarding COVID-19 and explained the precautions they need to take (28). At the same time, staff at the triage paid attention to the patient’s psychological issues, identified their negative emotions, actively provided comfort to the patients, and responded to and resolved unsatisfactory practices in a timely fashion. Triage staff were asked to adopt a passionate approach and to provide professional and quality care to all patients. As a result, we achieved the goal of zero complaints from patients and their families in The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Self-evaluation of the triage process

According to inspection requirements of the Guangdong provincial health commission, we developed the COVID-19 triage management self-evaluation form shown in Table 2. Regular and timely self-evaluation can serve to improve the quality of the triage process.

The effectiveness of this system in controlling infections

During this outbreak, an average of 1,794 patients and visitors came to The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University each day. Of the total 85,414 patients and visitors between January 22 and March 10, 2020 in this hospital, 359 patients were triaged to the COVID-19 fever clinic and 1,218 patients were triaged to the general fever clinic. A total of 187 suspected cases with COVID-19 were quarantined, and four of the suspected COVID-19 cases were diagnosed as being infected and referred to the designated treatment hospital. Using this off campus triage system, combined with intensive staff training, accurate assessment and triage, and timely referral, no inhospital cross infection was detected, and no complaints from patients and their families occurred during the outbreak. Up to September 10, 2020, no new cases of COVID-19 in The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University or its catchment area were detected.

Discussion

Experience with previous outbreaks of infectious diseases provides a basis for effectively responding to new outbreaks (29–31). During the outbreak of COVID-19 in Guangdong, China, we developed an effective off campus triage system at entry points to the departments of outpatient, emergency, and inpatient in The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University. Combined with intensive staff training and supervision, accurate assessment and triage process, and accurate and timely referrals, we have not missed any patient with COVID-19 infection, with no occurrence of inhospital cross infection, and no complaints from patients and their families in our hospital. The triage system deployed in The Seventh Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University may be used as a model for other centers in initial preadmission screening of possible cases of COVID-19. This model could be adopted to deal with future large-scale outbreaks of other infectious diseases.

There are several important lessons from the process in the creating and implementing the off campus triage system in our hospital that deserve further exploration. First, meticulous planning is critical for the success of this project. Hospital leadership consulted widely before creating this system, including not only with hospital staff but also with provincial leadership and government agencies on infection prevention and disease control, and worked out details on deciding the triage location, personal protection equipment, disinfection and other materials to be used at the triage points, questionnaires and forms for patients/visitors, and staff training and scheduling. Second, timely adjustment and modification of the triage system during the pandemic are important. Because COVID-19 was a new disease, our knowledge on it improved over time. Procedures developed at the beginning of the pandemic need to be evolved to reflect these changes over time. For example, during the pandemic, we modified the forms to better reflect the newly identified clinical symptoms and epidemiologic history. Third, staff fatigue could pose a serious challenge to the system as staff may be tired and relax the originally developed rules/procedures. The hospital leadership realized this issue and made several rotations of triage staff, in addition to intensive inspections and reinforcements.

Compliance with ethical standards

Because of the nature of this study, we determined that it was not appropriate or possible to involve patients or the public in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination of this paper. Because this study used quality assurance data only, no ethical approval was required.

References

- Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg 2020; 76: 71–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034

- Ghinai I, McPherson TD, Hunter JC, Kirking HL, Christiansen D, Joshi K, et al. Illinois COVID-19 Investigation Team. First known person-to-person transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the USA. Lancet 2020; 395(10230): 1137–44.

- Khan S, Ali A, Siddique R, Nabi G. Novel coronavirus is putting the whole world on alert. J Hosp Infect 2020; 104(3): 252–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.019.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al for the China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(18): 1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

- Ravani P, Saxinger L, Chandran U, Fonseca K, Murphy S, Lang E, et al. COVID-19 screening of asymptomatic patients admitted through emergency departments in Alberta: a prospective quality-improvement study. CMAJ Open 2020; 8(4): E887–94. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200191

- World Health Organization. 2020. Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report-12. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports [cited 1 February 2020].

- Schultz CH, Koenig KL, Alassaf W. Preparing an academic medical center to manage patients infected with Ebola: experiences of a university hospital. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2015; 9(5): 558–67. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.111

- Graham K, Mohammad N, Rehman H, Nazari A, Ahmad M, Kamal M, et al. Insecticide-treated plastic tarpaulins for control of malaria vectors in refugee camps. Med Vet Entomol 2002; 16(4): 404–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00395.x

- Wang XY. Construction and management of isolation tents for infectious diseases in shallow health care. Chin J Traditional Chin Med 2015. Available from: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?FileName=SXHZ202004005&DbName=CJFQ2020 [cited 12 February 2020].

- Ying J, Zhao J, Li XX. Hospital infection management and control measures for disaster relief temporary medical tents. Chinese J Nosocomiol 2009; 19(01): 116.

- Zhang D, Yu Y, Chen JH, Zeng TY, Wang H. Management practice of COVID-19 infection in large general hospitals. Chin Nurs Res 2020; 34 (4): 565–6.

- Chen CP, Zhu XP, Wang YM. The control of nosocomial infection during the SARS epidemic. Nurs Res 2004; 04: 364–5.

- Wu XF. Experience in the management of out-patient pre-diagnosis of H1N1 influenza. J Nurs Rehabil 2009; 8(12): 1049–50.

- Al-Tawfiq JA, Rothwell S, Mcgregor HA, Khouri ZA. A multi-faceted approach of a nursing led education in response to MERS-CoV infection. J Infect Public Health 2018; 11(2): 260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.08.006

- Cheng VC, Wong SC, To KW, Ho PL, Yuen KY. Preparedness and proactive infection control measures against the emerging novel coronavirus in China. J Hosp Infect 2020; 104(3): 254–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.010

- Li JJ. Prevention and control of H1N1 influenza in hospital outpatient clinic. Chin Foreign Med Res 2013; 11(21): 142–3.

- Song JH, Zhang Q. Prevention and control of H1N1 influenza in hospital outpatient clinic. Chin Gen Pract Nurs 2010; 8(14): 1290–1.

- Chang, XuH , RebazaA , SharmaL , Dela CruzCS . Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8(3): e13.17. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7

- Borgundvaag B, Ovens H, Goldman B, Schull M, Rutledge T, Boutis K, et al. SARS outbreak in the Greater Toronto Area: the emergency department experience. CMAJ 2004; 171(11):1342–4. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031580

- Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, et al. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1986–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685

- Seto WH, Tsang D, Yung RW, Ching TY, Ng TK, Ho M, et al. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). Lancet 2003; 361: 1519–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13168-6

- Burkle FM Jr, Burkle CM. Triage management, survival, and the law in the age of Ebola. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2015; 9(1): 38–43. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2014.117

- Varughese S, Read JG, Al-Khal A, Abo Salah S, El Deeb Y, Cameron PA. Effectiveness of the Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus protocol in enhancing the function of an Emergency Department in Qatar. Eur J Emerg Med 2015; 22(5): 316–20. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000285

- Sun XL. Role of the pre-diagnosis room in the prevention and control of H1N1 influenza in general hospitals. Chin J Nosocomiol 2020; 20(08): 1083.

- The State Council of the People's Republic of China. Medical Waste Management Regulations 2003. Available from: https://baike.so.com/doc/4823026-5039615.html [cited 20 February 2020].

- Bai ML. Application of humanized nursing in fever outpatients. Inner Mongolia Med J 2016; 48(11): 1386–7.

- Song P, Luo Y. Problems and countermeasures in the nursing and management of infectious diseases in China. J Nurs Admin 2010; 10(05): 345–6. doi: 10.5539/ijbm.v5n10p211

- Li C, Liu H, Ma SY, Zhu QM, Li MY, Ding TT, et al. The investigation and analysis of the current situation of nurse-patient communication and its influencing factors in a provincial Grade 3A hospital. Chin Gen Pract Nurs 2017; 15(07): 866–8.

- Saunders-Hastings P, Crispo JAG, Sikora L, Krewski D. Effectiveness of personal protective measures in reducing pandemic influenza transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemics 2017; 20: 1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2017.04.003

- Saunders-Hastings PR, Krewski D. Reviewing the history of pandemic influenza: understanding patterns of emergence and transmission. Pathogens 2016; 5(4): E66. doi: 10.3390/pathogens5040066

- Saunders-Hastings P, Reisman J, Krewski D. Assessing the state of knowledge regarding the effectiveness of interventions to contain pandemic influenza transmission: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS One 2016; 11(12): e0168262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168262